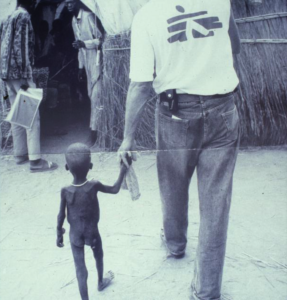

Long ago an MSF (Doctors Without Borders) poster transfixed one junior doctor. Me.

It was black and white. Two figures, photographed from behind, dominate the foreground: a poor black child, desperately malnourished and in need (yet another African war?), being led by a white man (a doctor maybe?) to a makeshift clinic that is but a grass hut. In the background, a black man in sandals with x-rays in a plastic bag tries to talk his way past another black man at the clinic entrance. We know that with his guardian our little black child will get past the gatekeeper.

It was black and white. Two figures, photographed from behind, dominate the foreground: a poor black child, desperately malnourished and in need (yet another African war?), being led by a white man (a doctor maybe?) to a makeshift clinic that is but a grass hut. In the background, a black man in sandals with x-rays in a plastic bag tries to talk his way past another black man at the clinic entrance. We know that with his guardian our little black child will get past the gatekeeper.

It’s all here: a dangerous place, a boy in need, a white hand reaching down, and salvation—improvised and temporary—ushered in. Back then poverty was far away. It happened to other people (people of colour, definitely needy, always weak) in dangerous situations they’d inadvertently caused. Enter aid: strong and white and good. Not responsible, but caring. Reaching down. Helping . . . Enter me.

Poverty was black and white: their problems, our aid. Their wars, primitive farming, illiteracy, excess children, backward traditions, religious superstitions, and poor work ethic solved by good governance, science, medicine, contraceptives, appropriate technology, education, economics . . . and the rest. I joined MSF, went to Colombia, immunised indigenous children there, fought plasmodia, and learnt about the world and myself. My subsequent journey from working in medicine to development has coloured and nuanced that.

Working on community based adaptation (CBA) in Madhya Pradesh (Central India), I saw indigenous communities toppling domino-like: drought causing crop failure, forcing men to migrate, leaving vulnerable women whose malnourished children died. Cause and lethal effect. Nobody asked who caused the drought.

“Kya karna?” (What can one do?), they’d say, shrugging.

At what point should I intervene? Medically treating malnourished children, implementing social programmes for mothers, establishing safe migration programmes for the men, or bringing in agricultural experts to introduce drought resistant crops? Should I work against drought?

A woman told me she’d prayed and prayed: “Barish (rain), barish, barish.”

No rain came but (“by luck,” she said) a man did. Promising city jobs, he pressed 4000 rupees into her hand and took her girl. I listened aghast. That was a horseman of apocalypse (aka climate change) dragging her daughter off to a Delhi brothel. A horseman unleashed not by her (tiny) carbon footprint, but by mine.

Poverty is injustice personified. A few years ago my family of six lived in a Delhi bustee (squatter settlement) built, like any other human structure, on piled-up hierarchies. Three tottering floors up, our 2×4 metre “penthouse” enjoyed light and air. In the windowless basement, Iqbal was baking bread from 4 AM. In 50 degrees. For 50 rupees a day. Was it his work ethic? Should I tell farmers eking crops out of arid land that hard work earned me my place in the sun? I’ve never worked like that mother with a baby begging on my railway platform at midnight. And the barefoot Bihari* boy shrouded in toxic fumes, pouring tar from a barrel? I sit wordless in my hospital jeep as he makes my road.

Not guilty! I recycle, vote left, buy Fair Trade. I worked hard, studied philosophy then medicine. True manicured Cambridge lawns, then clean New Zealand hospitals, materialised magically (“by luck,” he said) around me. OK, meanwhile horsemen were dragging off indigenous girls, Bihari boys, and other human sacrifices—but that was far away . . . Yet it was my world’s horsemen. Undeniably. “My verdict?” Guilty by association.

I can’t sit wordless. “All right,” I say to anyone who blames “them,” who presents the playing field as level, excludes poor people, or denies responsibility for their poverty and problems. “Isolate yourself. Properly.”

Not a wall, make a perspex dome. Keep your deathly shroud of CO2 inside. Play in there by yourself with your high-tech war toys and torture your own citizens. Keep your free market’s unsheathed claws off the world’s human and natural resources. Own these injustices—and the rest—and you’re not involved. Otherwise accept that “they” don’t have enough because we snatch too much. It’s lethal cause and effect.

Every day I’m reminded of how I’m connected to poverty. The girl on the rubbish heap is picking through my values. Uncomfortably. Long after I press five rupees into his palm the beggar’s unspoken “Why me, not you?” lingers. Inescapably. Tying my laces reminds me I’m cinched to women making shoes in Indonesian sweatshops. Involved. My mother’s medical specialist in New Zealand is a Pakistani snatched from people with fewer doctors and far greater needs. Greedily. Elsewhere Nepalis, uneducated and unsnatched, travel their own risky roads. Some finish corralled in Qatar, building hotels and soccer stadia for our next World Cup. Some die. So it goes.

Uncomfortably, inescapably, greedily, I am involved in mankind. Participant and perpetrator. Back then that poster affirmed me as a doctor but, beckoning me out beyond my borders, it also tunnelled into my humanity. It still does.

An ark sails stormy waters. I’m in it. Me and seven billion others who wake to the same yellow sun, breathe the same air. Some barely eat, others fly to ski resorts. Surging consumption, rising seas, falling biodiversity, waves of migration, and outbreaking wars are swamping the windowless below deck. Swamping us: if they sink we go down too, deckchairs and all. We globalised resources long ago, creamed off labour, threw back pollution, added yet another of our “military interventions” . . . and brought poverty aboard. Inadvertently.

Now a bell tolls.

*Bihar is one of the poorest of India’s states. Bihar’s adults and children are seen all over India as exploited migrant labourers.

Jeph Mathias is an Indian/New Zealand doctor and development specialist.

He lives in the Indian Himalayas and works on social and environmental issues around South East Asia.

Competing interests: None declared.