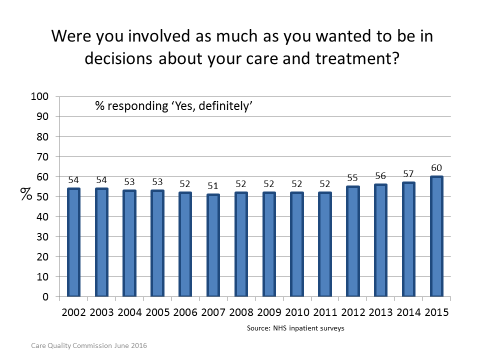

Shared decision making has now entered common parlance. Everyone seems to be talking about it and the term pops up frequently in report after report. But we can’t assume it’s fully embedded in mainstream clinical practice just because it’s talked about a lot. On the contrary. A recent review from the Care Quality Commission found hardly any change over the past ten years in the extent to which patients feel informed and involved in decisions about their care. And this is despite the almost universal consensus about the need for person-centred care, of which shared decision making is the prime embodiment.

Shared decision making has now entered common parlance. Everyone seems to be talking about it and the term pops up frequently in report after report. But we can’t assume it’s fully embedded in mainstream clinical practice just because it’s talked about a lot. On the contrary. A recent review from the Care Quality Commission found hardly any change over the past ten years in the extent to which patients feel informed and involved in decisions about their care. And this is despite the almost universal consensus about the need for person-centred care, of which shared decision making is the prime embodiment.

Ethical and legal guidance from the General Medical Council, the Supreme Court, and the Mental Capacity Act now speaks with one voice—shared decision making should be the default and very few exceptions are permitted. It is embodied in NICE quality standards, is a key theme in the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Choosing Wisely initiative, and in the NHS Five Year Forward View. Yet many practitioners have continued to resist these blandishments to cede decision making power to patients.

But maybe, just maybe, the tide is turning at last. The latest results from the annual survey of patients’ experience of hospital inpatient care, published last week, show an encouraging upturn in the number of people who said they were “definitely” involved in decisions about their care “as much as they wanted to be.”

What might explain this improvement?

Last year NICE convened the Shared Decision Making Collaborative, a wide group of stakeholders including representatives from NHS England, Health Education England, the General Medical Council, the Health Foundation, National Voices, and several Royal Colleges to discuss what needed to be done to embed shared decision making in mainstream practice. The group’s consensus statement called for stronger leadership to change clinical practice, training in shared decision making knowledge and skills, better provision of patient decision aids and incorporation of these into clinical guidelines, routine measurement of patients’ experience of decision making, and more research into implementation strategies.

Recently the group reconvened to review progress. We heard from projects around the country, including NHS England’s Right Care programme which is encouraging commissioners to promote shared decision making, NICE’s work on integrating patient decision aids into its clinical guidance, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ attempts to tackle overuse by actively involving patients, and programmes in London, Scotland, Wales, and north west England where shared decision making is a key theme.

All this amounts to a useful ragbag of initiatives rather than the coordinated strategy that the collaborative is calling for, but it is a good start and it does appear to be bearing fruit. In the meantime, Anu Singh told us about NHS England’s high level plans to ratchet up the effort as part of NHS England’s new self-care strategy. We must do all we can to ensure that this commitment isn’t allowed to wither away due to post-Brexit distractions.

Angela Coulter works in the Health Services Research Unit at the University of Oxford and for the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. She is a trustee of National Voices and a member of The BMJ’s Patient Panel.

Competing interests: Angela’s full declaration of competing interests can be found here.