Last week I discussed how drugs get their International Nonproprietary Names (INNs). The World Health Organization’s expert panel that assigns INNs has nine principles to guide its decisions, two primary and seven secondary. Here they are in abbreviated form:

Last week I discussed how drugs get their International Nonproprietary Names (INNs). The World Health Organization’s expert panel that assigns INNs has nine principles to guide its decisions, two primary and seven secondary. Here they are in abbreviated form:

1. The names should be distinctive in sound and spelling. They should not be inconveniently long and should not be liable to confusion with names in common use.

2. The names of pharmacologically related substances should, where appropriate, reflect the pharmacological relationship. [This is done by the use of stems, described below.]

3. When naming the first substance in a new group, consideration should be given to the possibility of devising suitable INNs for related substances belonging to the group.

4. In devising INNs for acids, one word names are preferred; their salts should be named without modifying the acid name, for example, “oxacillin” and “oxacillin sodium”.

5. INNs for substances that are used as salts should in general apply to the active base or the active acid. Names for different salts or esters of the same active substance should differ only in respect of the name of the inactive acid or the inactive base. The cation and anion of a quaternary ammonium substance should be named as separate components of the substance and not in the amine-salt style.

6. The use of an isolated letter or number should be avoided; hyphens are also undesirable.

7. To facilitate translation and pronunciation, use “f” instead of “ph”, “t” instead of “th”, “e” instead of “ae” or “oe”, and “i” instead of “y”; the letters “h” and “k” should be avoided.

8. Names proposed by whoever discovered or first developed and marketed a compound, or names already officially in use in any country, should be given preferential consideration.

9. Group relationships should if possible be shown by using a common stem.

The heart of this system is the stem, technically called a hyperonym. It is usually a suffix, but may be a prefix (for example, cef- for cephalosporins) or an infix (for example, -prost- for prostaglandins, which is also used as a prefix and suffix). Here are examples, illustrating some problems:

• The stem -olol indicates beta-adrenoceptor antagonists (beta-blockers), but stanozolol is not a beta-blocker and some beta-blockers do not end in -olol.

• The stem -vastatin indicates HMG coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (“statins”) but other names ending in -statin (for example, nystatin, pentostatin) are not statins.

• The stem -rsen indicates antisense oligonucleotides (for example, fomivirsen, trecovirsen), but this class is named from structure and general not specific pharmacological action.

Substems (hyponyms) can also be used. For example, the stem -ast, which indicates non-antihistaminic drugs used to treat asthma or allergies, can be expanded into more specific substems, such as -lukast for leukotriene receptor antagonists and -trodast for thromboxane A2 receptor antagonists.

I have recently been involved, with colleagues in Swansea, in a project whose aim was to determine to what extent the WHO’s naming process follows these principles, or at least some of them (numbers 1, 2, 6, and 7), surveying 7987 INNs.

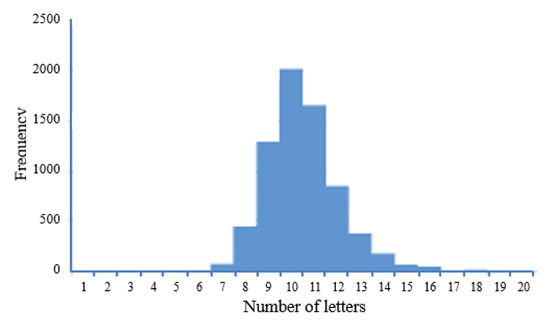

The figure shows the frequency distribution of the numbers of letters in 7111 INNs (see principle 1 above); the other results can be found elsewhere. In summary, the stems used to show pharmacological relationships are not spelled consistently and the principles do not impose an unequivocal order on the INNs, making it sometimes hard to understand their meanings. Furthermore, pairs of INNs that share a stem (whether appropriately or not) often have high degrees of similarity and thus have greater potential for confusion. This reflects the unavoidable tension between the use of stems to denote meaning and the aim of reducing similarities in the names of compounds.

The main clinical relevance of this work relates to the likelihood of medication errors, which can occur when medications have similar looking or similar sounding names. These so called look-alike, sound-alike (LASA) errors have been estimated to account for about one in every four medication errors in the US.

Next week I shall discuss the problems of naming biosimilars.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.