The common pejorative names for peddlers of ineffective medicines relate to advertising.

The common pejorative names for peddlers of ineffective medicines relate to advertising.

A quack, wrote Ambrose Bierce in The Devil’s Dictionary, is “a murderer without a license”. The origin of “quack”, originally “quacksalver”, is unclear. One explanation is that they “quacked” or boasted about their salves. This has a feeling of folk etymology about it, but alternative explanations are not very convincing either. Perhaps it comes from kwak, a Dutch word for a scrap, a remainder, or rubbish, or from kwakken, to fling down. However, these and other proposed etyma postdate quacksalver and are unlikely to be relevant.

The origins of “mountebank” and “charlatan” are more straightforward. A mountebank was a man who would climb onto a soapbox (Italian montare in banco) to shout his wares at a fair; a similar word, saltimbanco, came from saltare in banco, not just climbing but leaping. A charlatan was wont to babble or prattle (Italian ciarlare) about his wares.

A Dr Quackenbush is mentioned in Becky Sharp, the first three-colour Technicolor feature film, Rouben Mamoulian’s 1935 version of Vanity Fair, based on a play by Langdon Mitchell. When the scriptwriters of the 1937 Marx Brothers’ movie A Day at the Races were trying out names for the doctor (actually a vet) that Groucho was to play they settled on Hugo Z Quackenbush, only to find that there were over 30 doctors of that name in the US. Worried that they might be risking litigation if they used it, they changed it to Hackenbush.

In later life, Groucho met a real quack, Louisiana State Senator Dudley J LeBlanc, when he interviewed him on his quiz programme You Bet Your Life on 28 February 1951.

LeBlanc: Last year I made 5 million dollars.

Groucho: How did you manage to make 5 million dollars in one year, Senator?

LeBlanc: Well, you know, I own the LeBlanc Corporation that makes Hadacol—we manufacture Hadacol.

Groucho: Hadacol. What’s that good for?

LeBlanc: Well it was good for 5 million dollars for me last year.

In 1943 LeBlanc fell ill and after unsuccessful treatment in mainstream hospitals turned to an old friend, who gave him a patent medicine. LeBlanc discovered that it contained B vitamins, and thought that that was the secret of his cure. He started peddling a mixture of thiamine, riboflavin, nicotinamide, pyridoxine, and pantothenic acid, mineral salts (ferrous lactate, ferric, manganese, and calcium glycerophosphates, and calcium hypophosphite), and 12% alcohol “as a preservative”. Since the southern states were at that time liquor free, the profits from what he called Hadacol may have had not a little to do with that.

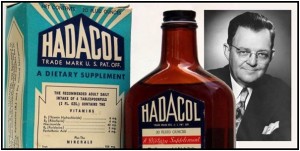

To advertise Hadacol LeBlanc (picture) revived the travelling medicine show, which had originated in the banning of theatres and circuses in Europe by the Christian Church in the sixth century, forcing performers to take to the road. Someone introduced a tooth-pulling act and sales of medicines followed. The shows spread across Europe and thence to America, where they consisted of dance acts and Vaudeville routines, interspersed with testimonials, performed by the entertainers, for patent or proprietary medicines. Such shows became less common when quacks started advertising their wares in newspapers and later on television.

Image: Dudley LeBlanc (1894-1971) and Hadacol

LeBlanc’s medicine show, the Hadacol Caravan, toured the southern states, playing one night stands to thousands. The entrance fee was Hadacol box tops—one for a child, two for an adult. Performers included Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, Carmen Miranda, and Judy Garland. Bill Nettles and his Dixie Blue Boys recorded “Hadacol Boogie” and others covered it, including Jerry Lee Lewis. Then came “Hadacol Corners” (Slim Willet), “Drinkin’ Hadacol” (Little Willie Littlefield), and “Hadacole That’s All” (The Treniers). Captain Hadacol was a comic book superhero; all he had to do to transform was to take a swig.

Why “Hadacol”? LeBlanc supposedly shortened it from a previous business, the Happy Day Company, plus L for LeBlanc. But then as he said himself, “I had-a-call it sumpin’!”

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.