A happy New Year to both my readers. And what a cornucopia of anniversaries we can celebrate this year. Take your pick. The topics are diverse (see also the pictures below):

- anatomy (Mondino de Luzzi);

- physiology (Realdo Colombo, William Harvey, and Caleb Parry);

- pharmacology (glossopetrae, penicillin, and post-coital contraception);

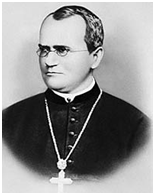

- genetics (Fortunio Liceti, Gregor Mendel, and John Langdon Down);

- neurology (Guillain–Barré syndrome and Rett syndrome);

- psychology/psychiatry (Julius Ludwig August Koch, Eugen Bleuler, Lewis Terman);

- ophthalmology (macular pigment);

- tropical diseases (Patrick Manson);

- surgery (joint replacement and radical mastectomy);

- inventions (the stethoscope, the clinical thermometer, hypnotism);

- first editions of well known textbooks (The Parmacological Basis of Therapeutics and Mendelian Inheritance in Man);

- new institutions (the St Mary’s Dispensary for Women and Children, London, The Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases, Berlin, the first birth control clinic in the USA, and Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge).

For me, the word that cries out for explanation from among all these topics is “stethoscope”, which René Laennec invented in 1816. He described his invention to l’Académie des Sciences in 1818 and in a book, De l’auscultation médiate, in 1819:

Je fus consulté, en 1816, pour une jeune personne qui présentait des symptômes généraux de maladie du cœur, et chez laquelle l’application de la main et la percussion donnaient peu de résultat à raison de l’embonpoint. L’âge et le sexe de la malade m’inlerdisant l’espèce d’examen dont je viens de parler, je vins à me rappeler un phénomène d’acoustique fort connu: si l’on applique l’oreille à l’extrémité d’une poutre, on entend très-distinctement un coup d’épingle donné à l’autre bout. J’imaginai que l’on pouvait peut-être tirer parti, dans le cas dont il s’agissait, de cette propriété des corps. Je pris un cahier de papier, j’en formai un rouleau fortement serré dont j’appliquai une extrémité sur la région précordiale, et posant l’oreille à l’autre bout, je fus aussi surpris que satisfait d’entendre les baltemens du coeur d’une manière beaucoup plus nette et plus distincte que je ne l’avais jamais fait par l’application immédiate de l’oreille.* (See footnote for translation)

Laennec found that a wooden cylinder gave the best results, and he described the various sounds one could hear, calling them râles légers, râles muqueux, râles crépitants, sifflement, pectoriloquie, and égophonie; a pleural rub he described as “un râle fort et sonore”.

Laennec also invented the word “cirrhosis”, from the Greek κιρρός, orange-tawny, because he saw yellowish granules in the liver, which turned out to be bile-stained acini.

But why did he call his invention “un stéthoscope”? It comes from two Greek words. First, στῆθος, the anterior chest, the front part of the θώραξ, specifically as the seat of the heart, the voice, and the breath; Laennec’s choice of this particular word suggests that he was very familiar with Greek. As to the second part of the word, he might have chosen φωνεῖν, to make a sound, or some word meaning to listen or hear, such as ἄκουειν or κλύειν. Instead he chose σκοπεῖν, which means to look at, contemplate, or inspect [visually]. But σκοπεῖν can also mean to look after or protect, to consider, or to examine other than visually, for example, to examine one’s own affairs or the laws of a place. And ἄκουειν, κλύειν, and σκοπεῖν can all mean to obey. The earliest of about 200 words in the OED ending in –phone is kaleidophone (1827), whereas of 300 words ending in –scope, about 40 date from before the 19th century, the earliest being horoscope (1050). In 1816, therefore, “stethoscope” was the natural choice.

Twenty eight medical anniversaries in 2016

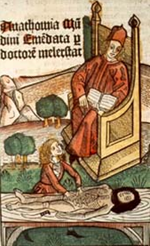

1316

Mondino de Luzzi, Anatomia Corporis Humani

1516

Realdo Colombo, Italian anatomist, born (died 1559)

1616

William Harvey, Lumleian Lecture on the circulation of the blood

1616

Fortunio Liceti, De Monstrorum Natura

1616

Fabio Colonna, “De glossopetris dissertatio” (fossil teeth used therapeutically)

1766

Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, completed

1816

René Laennec invents the stethoscope

1816

Caleb Parry, An Experimental Inquiry into the Nature, Cause and Varieties of the Arterial Pulse

1841

James Braid attends a public demonstration of animal magnetism by Charles Lafontaine, and invents hypnotism

1866

Gregor Mendel, Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden

1866

Max Schultze describes the function of macular pigment

1866

John Langdon Down, Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots

1866

Thomas Clifford Allbutt invents the clinical thermometer

1866

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson opens the St Mary’s Dispensary for Women and Children in London, later the New Hospital for Women and Children

1866

Patrick Manson, starts work in China

1891

Themistocles Gluck, first joint replacements, using ivory

1891

William Halstead, radical mastectomy for carcinoma of the breast

1891

Julius Ludwig August Koch, Die psychopathischen Minderwertigkeiten, introduces the concept of psychopathology

1891

Robert Koch, The Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases, Berlin

1916

Eugen Bleuler, Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie

1916

Margaret Sanger opens the first birth control clinic in the USA and publishes What Every Girl Should Know

1916

Georges Guillain, Jean Alexandre Barré and André Strohl (from left to right) describe a syndrome of the peripheral nervous system

1916

Lewis Madison Terman, The measurement of intelligence, describing the Stanford Revision of the Binet-Simon Scale (IQ testing)

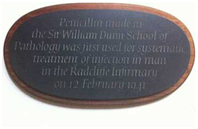

1941

First clinical use of penicillin in the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford

1941

Louis S Goodman (left) & Alfred Gilman, The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 1st edition

1966

John McLean Morris and Gertrude Van Wagenen describe post-coital contraception

1966

Victor A McKusick, Mendelian Inheritance in Man, 1st edition

1966

Andreas Rett describes Rett syndrome

*“In 1816 I was consulted by a young woman with general symptoms of heart disease, in whom palpation and percussion were of little use because of her obesity. Her age and sex prohibited me from using the method of examination that I have just described [i.e. direct auscultation], but I remembered a well known acoustic phenomenon: if one puts one’s ear to the end of a beam, one can distinctly hear a pin scratching at the other end. I thought that this physical property could be useful in a case such as this. I took a notebook, rolled it up tightly into a cylinder, applied one end of it to the precordium, and put my ear to the other end. I was as surprised as I was gratified to hear the heart beats much more clearly and distinctly than I had ever done by direct auscultation.”

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

![aronson_newyear8]](https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/files/2015/12/aronson_newyear8.png)