The Old English dictionary called the Epinal glossary, glossed the Latin word “bile”, a form of bilis, as “átr”, later spelt atter, meaning gall or bitterness. However, “atter” and “bile” or “gall” are not etymologically connected. The Indo-European root ATR meant fire, and by association blackening caused by fire; bile and gall came from GHEL, bright, smooth, shiny.

The Old English dictionary called the Epinal glossary, glossed the Latin word “bile”, a form of bilis, as “átr”, later spelt atter, meaning gall or bitterness. However, “atter” and “bile” or “gall” are not etymologically connected. The Indo-European root ATR meant fire, and by association blackening caused by fire; bile and gall came from GHEL, bright, smooth, shiny.

GHEL gives us a gallimaufry of shiny words: glare, glass and glaze, gleam, glimmer, glint, glitter, glitz, glow, and gloss (but not glossary). Shiny ice (French glace) is gelid and glacial; it’s also slippery, like glacis, glide, glissando, and being glib. Gleet is a slimy discharge, as in gonorrhoea. Glabrous (Latin glaber) means smooth and hairless, like the glabella, the space between the eyebrows.

Gold and yellow are bright colours and to gild is to cover with gold. The Dutch guilder and the Polish zloty were gold coins. The yolk is the yellow, the glair the white of an egg, both shiny, as are gelatin, jelly, and gels, such as alcogel and hydrogel. A Latin word for yellow, helvus, is related to fel, another word for bile. And fell felons were full of bitterness or venom.

Glaucous (Greek γλαυκός) means bluish-green or grey, like the glaucous gull (Larus glaucus) and the vision in glaucoma. From Greek χλωρός (chloros), we get the green gas chlorine and chlorinated drugs, including chlorambucil, chloramphenicol, chlordiazepoxide, chlormadinone acetate, chloroform, chlorothiazide, chlorotrianisene, chlorphenamine, chlorpromazine, chlorpropamide, chlortalidone, chlortetracycline, and chlorzoxazone, the disinfectant chlorhexidine, and the green plant pigment chlorophyll. Chloasma was originally a greenish-yellow colouring of the face, from χλοάζειν, to turn green. The brown or black discoloration of the face in pregnant women, the mask of pregnancy, should properly be called melasma, but is more often called chloasma. Perhaps it was associated with the 19th century greenish-yellow colouring of the skin called chlorosis, which we no longer recognise, or rarely, and which was probably due to iron deficiency anaemia.

Drop the rho from χλωρός and you get χόλος, gall, bile, or anger, which makes you choleric and gives us the cholic acids, cholesterol, cholecalciferol, cholagogues, cholecystectomy, cholangiectasis, chloangiocarcinoma, cholangiography, and many more like them, including one of the longest medical words, hepaticocholangiocholecystenterostomy, all 37 letters of it.

Cholera was originally a form of gastroenteritis, with severe diarrhoea, bilious vomiting, and abdominal cramps. It typically occurred in the summer and was also called bilious, summer, or European cholera, to distinguish it from what we now call cholera, the diarrhoeal disease that is specifically due to the Vibrio cholerae, also called Asiatic, epidemic, catarrhal, Indian, malignant, Oriental, or serous cholera. The former was recognised in the 16th century, the latter not until the start of the 19th, when pandemics were reported in India.

Being choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine, the four temperaments, came from the hypothesis that one’s mood and state of health depended on the amounts and balance of four bodily fluids, or humours: yellow bile from the liver, black bile from the spleen, phlegm (Latin pituita) from the pituitary, and blood (Latin sanguis) from the liver. Adust, from the Latin adustus, overheated, burnt, or scorched by the sun and therefore dusky, was used to describe the humours when abnormally concentrated; so choler adust was black bile. Atter and bile merge in atrabilious, affected by black bile or melancholic, which is black bile in Greek. Where I first trained as a junior doctor the local populace used to refer to the yellow bile (vomiting) and the black bile (a headache), usages I haven’t seen or heard of elsewhere.

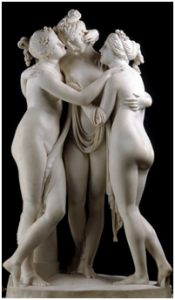

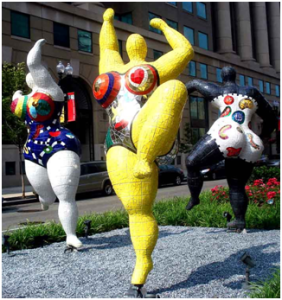

GHEL also gave Aglaia (splendour or joy), one of the bright Graces of Greek mythology, the others being Thalia (abundance or good cheer) and Euphrosyne (merriment). Sculptors and artists have interpreted the Graces in different ways (pictures). Canova, for example, depicted them as slimly graceful and Niki de Saint Phalle as rumbustiously cheerful; Rubens on the other hand, plumped (if that’s the right word) for something in between.

Images: The three Graces as depicted by Canova, Rubens, and Niki de Saint Phalle

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.