Most of the dozen words with medical connections that I found in the Old English dictionary called the Epinal glossary are obsolete, with modern equivalents. For example, átr or atter.

Most of the dozen words with medical connections that I found in the Old English dictionary called the Epinal glossary are obsolete, with modern equivalents. For example, átr or atter.

“Atter”, meaning poison, gall, or, figuratively, bitterness, is not documented later than the 16th century, although it lived on, at least until the late 19th century, as a word meaning pus or the white fur that covers the tongue. The derivative attercop, a spider, fell out of general use by the end of the 17th century, but was still in figurative use in the late 19th century, meaning a venomous malignant person. “Attercop” may mean a cup of poison, but cop also itself meant a spider, as in cobweb. Although old fashioned, the word is still listed in modern dictionaries and occasionally crops up. Robert Graves, for example, published a poem called “Attercop: the all-wise spider” in a collection called Mock Beggar Hall (1924). And J R R Tolkien used it, first in a poem called “Errantry” (1933) and later in a ditty sung by Bilbo in The Hobbit (1937) when he leads giant spiders away from the dwarves trapped in their webs:

Old fat spider spinning in a tree!

Old fat spider can’t see me!

Attercop! Attercop!

Won’t you stop,

Stop your spinning and look for me?

Old Tomnoddy, all big body,

Old Tomnoddy can’t spy me!

Attercop! Attercop!

Down you drop,

You’ll never catch me up your tree!

Later Bilbo chants another song in which he calls the spiders “lazy Lob and crazy Cob”. In The Lord of the Rings Shelob is a giant female spider. The Northern version of attercop, ettercap, still appears from time to time in Scottish publications.

There is fossil evidence of an extinct spider-like species known as Attercopus fimbriunguis, literally the fibre-nailed spider, giving the earliest evidence of the use of silk by animals, not through spinnerets, as in modern spiders, but from glands on the abdomen.

Atterlothe, an antidote to poison, from lað, hostile, was a name given to various plants, such as Betonica and Morella species. Morella serrata is a South African plant that has been used to treat microbial infections and to enhance male sexual performance.

The Indo-European root ATR meant fire, and by association the blackening that fire can cause. Atrox in Latin, from which we get atrocious, denoted fierce heat, anything terrifying in appearance or alarming, and bitter feelings. Various dark colours were at one time described by words prefixed by atro-: atropurpureus, atrorubens, atrovirens; and atrosanguineous meant of a dark blood-red colour. The atrium, or hallway, of a house may have been a place where a fire was lit, its smoke blackening the ceiling; an interesting suggestion, but no more than that.

Atrabilious means literally affected by black bile and thus melancholic, which is the Greek for black bile. The Oxford English Dictionary surprisingly also defines “atrabilious” as “hypochondriac; splenetic”, terms that apply to other parts of the body. “Atrabilis”, also called “ater succus”, black juice, was, according to the New Sydenham Society Lexicon of Medicine and the Allied Sciences (1879), “a term anciently used for an imaginary fluid, thick, black, and acrid, supposed to be the cause of melancholia, when existing in excessive quantity [and] secreted by the adrenals.” I note that depression occurs in patients with hyperadrenalism and may be ameliorated by bilateral adrenalectomy.

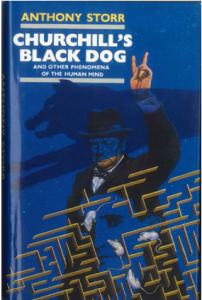

Hester Thrale described Samuel Johnson as having suffered from the black dog, a term that Winston Churchill later used to describe his bouts of depression. The late Anthony Storr suggested (picture) that Churchill’s achievements would not have been possible had he not so suffered, a phenomenon that George Pickering had already called “creative malady”. But for those of us who do not aspire to lead the country, perhaps what we need for the treatment of depression is an atrabilis receptor antagonist.

Churchill’s Black Dog and Other Phenomena of the Human Mind by Anthony Storr (Collins, 1989)

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.