Peter McIntyre, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute and University of Sydney.

Peter McIntyre, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute and University of Sydney.

Kristine Macartney, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute and University of Sydney.

Kristine Macartney, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute and University of Sydney.

Julie Leask, University of Sydney.

Julie Leask, University of Sydney.

Australia’s approach to improving low childhood vaccine coverage began with the “Immunise Australia” campaign launched by then Health Minister Wooldridge in 1997. A unique element was linkage of eligibility for social security payments to immunisation status, beginning in 1998 with eligibility for a single $200 payment, later escalated to include child care rebates, and in 2012 other family payments. Immunise Australia included other initiatives, such as incentives for general practitioners (GPs) to give and report vaccines and the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR), making it difficult to disentangle effects on uptake – an early study suggested linkage to child care payments was influential. Reported coverage for all vaccines included in the fully funded National Immunisation Program has been stable at around 92% since 2002, but is persistently up to 20% lower in small geographic areas. In 2013, reports of coverage down to postcode level were made publicly available for the first time. This created intense media interest, with one dominant theme being low coverage in more affluent areas, leading to “no jab, no play” – a newspaper campaign to allow childcare centres to ban unvaccinated children and for the federal government to stop paying family assistance payments to vaccine refusers.

Some state governments responded to this campaign by making documentation, but not receipt, of immunisation compulsory for childcare attendance in 2014.

Since benefit eligibility was linked to immunisation status in 1998, parents whose child was not fully immunised could retain eligibility by having an immunisation provider certify on a form that the risks of non-immunisation had been discussed on “conscientious” or religious grounds or that there was a medical contraindication to receiving a vaccine(s). On 12 April 2015, the Prime Minister and Social Security Minister announced that completion of a “conscientious objector” form would no longer result in retaining payment eligibility, and a week later following consultation with religious groups, that religious objection would also not be accepted. The Opposition Leader quickly agreed, cementing bipartisan agreement in the wake of polls indicating widespread public support and the broadly reported death of an infant from pertussis in February. These changes did not occur in a policy vacuum – major reviews of Australia’s welfare system and of early childhood learning had both recommended tightened immunisation requirements for benefit eligibility. The announced changes, some means tested and some not, could lead to an annual reduction in childcare rebate and other family payments approaching $A10,000, and government savings estimated by one source of $A50 million, and are set to come into force on 1 January 2016. On 19 April, Health Minister Ley announced a $A26 million package of measures to boost immunisation coverage, including additional payments to GPs undertaking catch-up immunisations , an immunisation awareness programme and expansion of the existing National HPV Vaccination Register to an Australian School Vaccination Register.

There are a number of uncertainties and logistic challenges around the implementation of these policy changes, but those voicing these have had short shrift with some sections of the media. The main uncertainty is the magnitude of any increase in immunisation coverage, both in low coverage areas and among the various distinct categories of incompletely immunised children. Review of initiatives to increase coverage from the US and from the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts of WHO found very limited evidence that financial penalties are effective while on the flip side, incentives remain effective. Logistic challenges include deficiencies in the ACIR – a recent study found that in more than half of cases, the reason no vaccines were recorded was failure of records to reach the ACIR (overseas delivered immunisation and mobility), whereas unregistered vaccine objection accounted for around 25%. Given bipartisan support, this Australian experiment seems certain to continue. If it can be comprehensively evaluated, this initiative will be an interesting addition to the evidence base on the impact of financial penalties on immunisation coverage. That evaluation would also need to consider any adverse impacts such as reduced participation in pre-school education and reduced trust in the immunisation program, as noted by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts review. Nevertheless, it is important to note that even at their now maximum level of enforcement, these measures still fall well short of as yet unpassed Californian legislation proposing that incompletely immunised children be required to home school in the absence of a medical exemption. It is equally important to note that clinicians interacting with vaccine-hesitant parents require a comprehensive set of skills and resources.

Competing interests: KM: None declared.

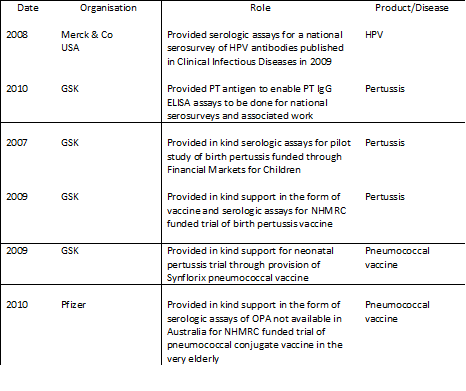

PM: I have read and understood the BMJ group policy on declaration of conflicts of interests and declare the following interests in addition to the organisation I head receiving funding from the Australian Government Department of Health :

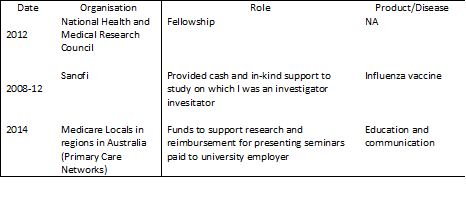

JL: I have read and understood the BMJ group policy on declaration of conflicts of interests and declare the following interests: