This blog is the first in a series about you, our readers. Fiona Godlee, the BMJ’s editor in chief, suggested I write a regular blog explaining some of our policies and procedures. Many of them have been in place for decades, but our readership of practising physicians and academic researchers may not be aware of many of them. I’ll aim to choose topics based on recent questions from readers around the world who see the journal in print, online, and on the iPad.

But firstly, why me? I edit bmj.com, and over the last five years I’ve written a number of articles about digital developments and future priorities at the BMJ. Secondly, a big part of that role is fielding reader queries. I and my colleagues in the web team get asked all sorts of questions.

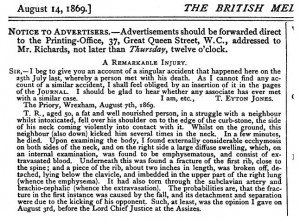

Yesterday, for instance, a US sports physician from Concord, North Carolina, wanted to know how to cite a BMJ article about first rib fractures, published in 1869. Readers like him were on our minds last week, when we held a BMJ editorial strategy session in Baltimore. I and some of my colleagues discussed what the hot issues are in US healthcare and how we should cover them in the journal.

Yesterday, for instance, a US sports physician from Concord, North Carolina, wanted to know how to cite a BMJ article about first rib fractures, published in 1869. Readers like him were on our minds last week, when we held a BMJ editorial strategy session in Baltimore. I and some of my colleagues discussed what the hot issues are in US healthcare and how we should cover them in the journal.

The BMJ is the first international medical journal to launch an online US edition. We now have 20 US employees, including a US news and features editor based in New York, and two research editors (one based in Washington, the other in Boston), plus a growing stable of freelance journalists and columnists working across the US.

One of the issues we considered in advance of the launch was how to accommodate US spelling and punctuation into BMJ house style. We resolved this by deciding that house style is to reflect the reader, not the author. This means that articles about the US that display online in the US edition should be in US English.

Laboratory values may be expressed using either conventional or Système international d’unités (SI) units, depending on what the author uses, with conversion factor expressed secondarily (in parentheses) only at the first mention.

Articles that contain numerous conversion factors may list them together in a box. In tables and figures, conversion factors may be presented in the footnote or legend. The metric system is preferred for the expression of length, area, mass, and volume. Conversion factors can be obtained via the Units of Measure table in the the AMA manual of style.

Our US edition launched in September 2012, so we now have some analytics data to help us decide what kind of articles are popular. This helps us to decide our editorial priorities for the coming year. Unsurprisingly, US readers have similar tastes to readers elsewhere. Investigations, research, and education articles get lots of traffic, along with Christmas BMJ articles .

But surprisingly, the most read article in the US in 2012 (34,231 US page views and counting) was a Finnish cohort study published on November 30. It explores the extent to which muscular strength in adolescence is associated with all cause and cause specific premature mortality.

So far the study has not been cited and has only had two responses, but it did attract lots of US press coverage, 1000 Facebook likes, and 128 tweets. The top five most read include Brian Deer’s January 2011 series on Andrew Wakefield and the impact of his 1997 Lancet paper false linking the MMR vaccine with autism. Here’s the top five articles read in the US in full.

- Muscular strength in male adolescents and premature death: cohort study of one million participants

- The truth about sports drinks

- Why Rudolph’s nose is red: observational study (Christmas paper)

- Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in Swedish women: prospective cohort study

- The difference in blood pressure readings between arms and survival: primary care cohort study

One response to the editorial published to make the launch of our US edition said: “I am attracted by the journal’s good writing, honesty, and relative absence of Marxist enthusiasm. This is in comparison to the NEJM and JAMA. Please remember that this American is interested in the mother country’s side of things.”

A second US reader who regularly responds to articles, told me: “I read the BMJ because it’s more than merely informative. It’s also appealing, personal, friendly, and diverse. In contrast, I find most US medical journals impersonal, pedantic, pretentious, and exclusive. But beneath these cosmetic differences, both BMJ and US medical journals share a subservience to Big Pharma, which limits medical progress.”

A third US reader told us: “The BMJ is more trustworthy than American journals, which rely on conflicted peer reviewers and depend on ads and supplements bought by pharma.

“American medicine is calculated so as to “not rock the boat.” In contrast, commentary on BMJ articles is much more intellectually-provocative with a more literate and livelier writing style. The BMJ provides maximum connection to cited materials. It is a pleasure to hunt down sources to assess accuracy of authors’ and commentators’ interpretations.

“The BMJ also provides many more open access reports than most American medical journals. [BMJ editor] Fiona Godlee is doing a first rate job. A world leader who displays great courage in addressing controversial issues that have domestic and international implications.

“Maybe “British” in ‘BMJ’ reflects the outlook of the former British empire. We Americans, in contrast, are so insular in our views! Dr. Godlee’s stance and the new BMJ policy relating to access to data underlying published research reports will profoundly affect the policies of medical journals everywhere. The mark of any great journal is its influence. The BMJ stands “heads and shoulders” above its peers.”

David Payne is editor, bmj.com