News and Events

“What happens when you die” event at Green Man Festival 2021.![]()

Listen to the event here.

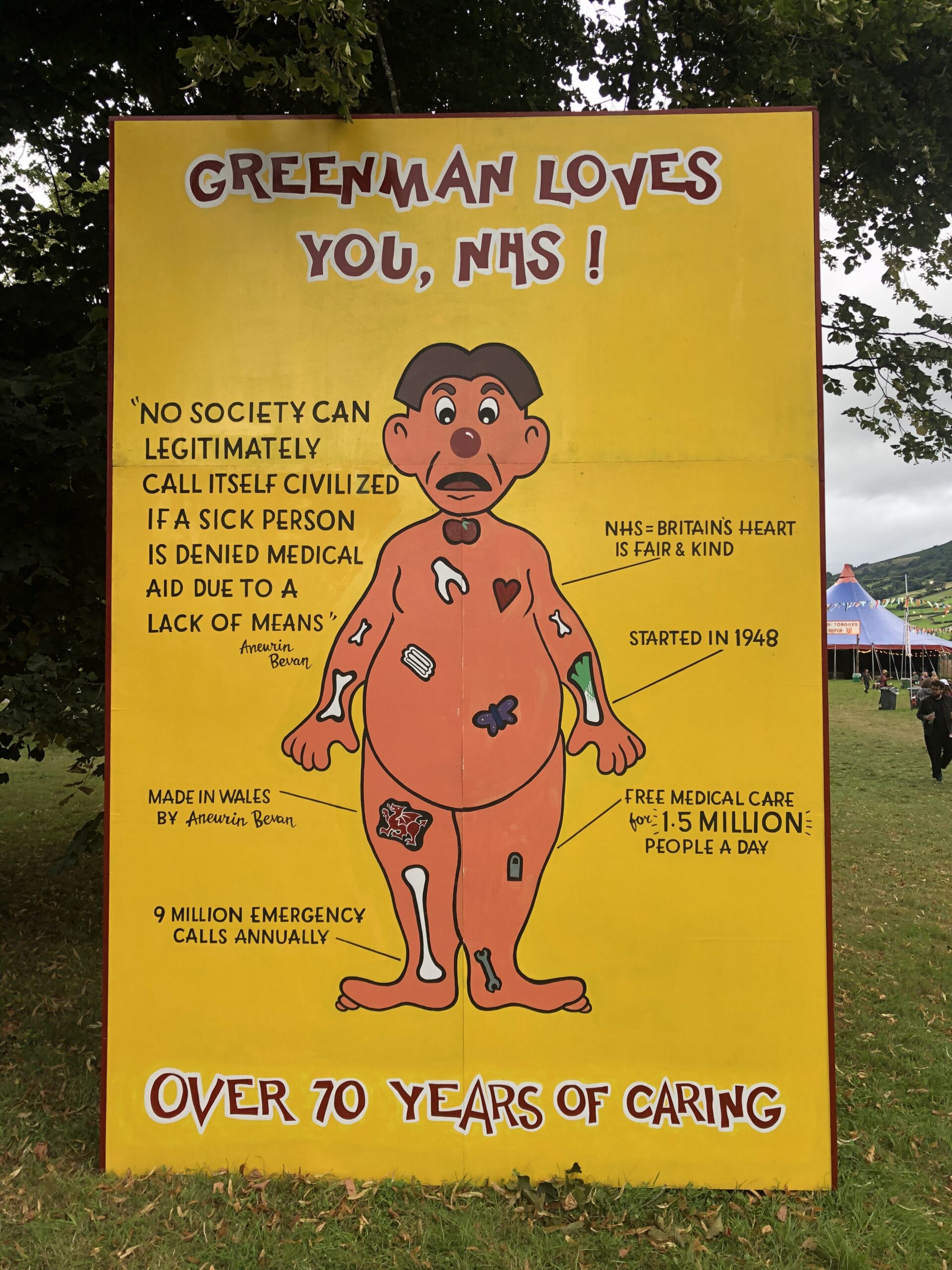

The Green Man Festival is Wales’ largest art festival, and it returned with furore and a large offering of musical and spoken word performances, after being cancelled in 2020.

Where better to discuss the important topic of death and dying? James Norris, Professor Mark Taubert and Guardian Arts journalist Jude Rogers were invited to do just this in Einstein’s Garden, which represents the science element that this festival prioritises. The title of the event, which was held in the Omni tent, was “What happens when you die?“.

The talk was chaired by Guardian music journalist Jude Rogers, who is writing a book on the topic of how music and culture affect every part of our lives, including the end. Jude met Mark at a ‘Nick Cave in Conversation’ event, where Mark asked the singer what his deathbed tune would be (to which Nick Cave gave a large scowl and replied: “No music at all, thank you!”). Mark also featured on a BBC Radio 4 programme produced by Jude called, ‘A Life in Music‘ about what music means to people at the end of their lives.

Attendees learned how much dying has changed, for the sheer complexity of our living. Questions from patients and their loved-ones about social media digital legacies after death are no longer uncommon in palliative care clinics, hospice visits and ward rounds and started a few years ago. Queries like, ‘Doctor, slightly random question, but what does actually happen to my Facebook when I die?’ have become more common. [1] And since Covid-19 has hit us, these questions continue, featuring in discussions on social media itself – often after a quite sudden and unexpected death. [2]

When asked, James Norris described himself as a ‘end of life technologist’ and possibly the only person in the world with that job title. His role has included developing an app that enables people to convey their wishes, thoughts, preferences and even fears well into posterity. Once documented they are shared with loved one’s when we are still alive. Sharing our wishes can be important and precious to relatives and next of kin, once we die. It can also be important when we are still alive (but less able to communicate, for example that we do not want Justin Bieber playing in the hospital/hospice room in our moments of frailty).

Heavy stuff, you might think, on a very mixed-weather Saturday afternoon, when in parallel tents, acts like Caitlin Moran or Ed Dowie were offering up their talent. But the Omni tent was packed, and there were also many young audience members and children. And there was much laughter, too. The notion, described by Mark, that palliative care wards and hospices are sombre places, can be put to rest. There is much welcome laughter and humour, and people don’t change their personality or their sense of what they find funny, just because they have been diagnosed with a life-limiting or terminal diagnosis. A sense of normality is what many people, who have had a serious illness diagnosed, want back desperately.

Jude wondered whether we have become better at exposing this as a taboo topic that needs to be openly talked about, and whether technology can help. James described that through apps and websites, the act of assigning a legacy contact, in Facebook, for instance, can be a real impetus for starting conversations about what will happen. Many have never considered how they want their Facebook, Twitter, PayPal, YouTube or even sports betting account managed after they have died, and it can be very difficult to access these accounts if there is no plan in place. Many people have not made a will, but even less have specified wishes to their loved ones around what they would want for their funeral (music, cremation, burial?). James Norris felt this was changing, with more and more people individualising their funerals a bit like is happening in the wedding industry.

“Do conversations about our preferences, including music at the end of life, lead to other, more serious topics, like a back door?” was a question put to Mark. Yes, music and culture can be a gateway to a person’s views on potential future medical interventions and ceilings of treatment. [3] This often includes discussions on advance care planning, and whether an individual with a serious illness where there is little prospect of cardiopulmonary resuscitation working, would want it considered or not. Topics like Do Not Attempt CPR forms can be tricky to broach [4], but remain very important. “We have them on a weekly basis and have to be open and honest when we think that certain treatments are unlikely to work”, Mark said.

What is, and what was important to you? Music, photos, videos? Would you prefer your phone to be locked into perpetuity after you die, or would you want others to access photos and videos on it? Would you (like James admitted to doing during this talk), like to record a rock tune that is to be played at your own funeral (gasps from Mark)? If the answer is yes, you need to put plans in place for this to happen. If good, comprehensive end of life care and advance planning is about making people feel more normal and helping them to conquer the demons of incurable illness, then surely this new digital connectivity must be addressed. Our social media presences are an integral property, a diary, an album, a life story with an address. Our lives and our personhoods are increasingly linked to the places of our online presence, and a Facebook, Instagram or Twitter page can take on a whole new meaning after someone has gone.

Dying without having laid out any plans at all for your digital content will make it complex for others. Help make things easier for those who remain. As an audience member pointed out later, ‘it is important to hold these conversations with your loved-ones BEFORE you have to.’.

If you would like more information on this topic, there is an accompanying article in the Metro newspaper which can be found here.

Listen to the event here.

References:

- Abel J, Kellehear A, Millington Sanders C, Taubert M, Kingston H. Advance care planning re-imagined: a needed shift for COVID times and beyond. Palliative Care and Social Practice. January 2020. doi:10.1177/2632352420934491

- Rietjens J, Korfage I, Taubert M Advance care planning: the future BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2021;11:89-91. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002304

- , , , , & (2018). Talk CPR – a technology project to improve communication in do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions in palliative illness. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0370-9

Addendum:

The Pagan mythology around the ‘Green Man’, and also the ‘Green Woman’, is often interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, the renewal of lush vegetation, representing the cycle of new growth that occurs every spring. The Green Man is most commonly depicted in a sculpture, or other representation of a face which is made of, or completely surrounded by leaves.