Blog by Swati Joshi

Still Parents is an award-winning exhibition that runs until 4 December 2022 at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester. The idea for it was born in the wake of the personal losses of its two curators, Lucy Turner and Imogen Holmes-Roe. In 2019, in collaboration with Manchester’s Sands (Stillbirth and Neo-Natal Death Charity), these women’s experiences of healing through art inspired their art workshops to help grieving parents cope with the trauma of losing a baby. The exhibition is an artistic sequel to grief sessions where parents share their stories of isolation and suffering. It shows how the grieving parents can express themselves through their art without the pressure of having to interpret the work. Artistic modes include anything from ceramics to embroidery to watercolour painting (and many more crafts and visual arts genres). The exhibition itself incorporates artworks made by the parents, who also designed the exhibition space, choosing the works they wanted to be displayed. This constituent-led curation empowers the grieving parents in the truest sense.

The exhibition took me back to a time when my mother and grandmother would sit me down and narrate my great grandmother Panji’s experience of losing her babies. I remember her as a frail, old, white figure wrapped in a thin, cotton saree expressing her feelings. She felt as if her uterus had loosened and that she would defecate it someday. While seeing the Still Parents exhibits, I could hear again my great grandmother’s traumatic experiences. Panji and her husband Anna (a Marathi sobriquet for my great grandfather) suffered three stillbirths, two boys and a girl. My maternal grandmother, Aji, was the first of their children to survive, and she was raised by foster parents until they were certain she would make it past infancy. Through this piece, I aim to help others appreciate the founders’ initiatives and to pay tribute to the babies lost in my family, whom I have always remembered as the yet-to-be-known, hovering in that limbo that is the space of memory and mourning.

During their grief sessions with the Still Parents project, participants express their pain with no pressure to interpret their artwork. The activity gives them an opportunity to birth an artistic mode of self-care, and to “parent” an artistic creation that distracts their minds from trauma. One of the participants shared this insight with me: “The task would keep the hands busy.” And that is the beauty of the artistic sessions conducted by Turner and Holmes-Roe. Since the participants are not expected to describe or explain their artistic creations, they can liberate themselves through impactful visual narratives.

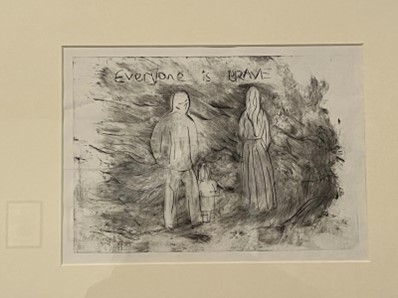

During my visit, I was fascinated with how various participants interpreted Edward Munch’s painting, “Two People: the Lonely Ones” (1899). One of them described it as a lonely experience of suffering for the couple represented in the painting, whereas another said that each partner was giving the other space to heal and grieve. Ruth Chester-Lees (see Figure 2) interpreted Munch’s painting by sketching the portrait of her daughter in it, while Laura Brunt (see Figure 3) made a ceramic sculpture.

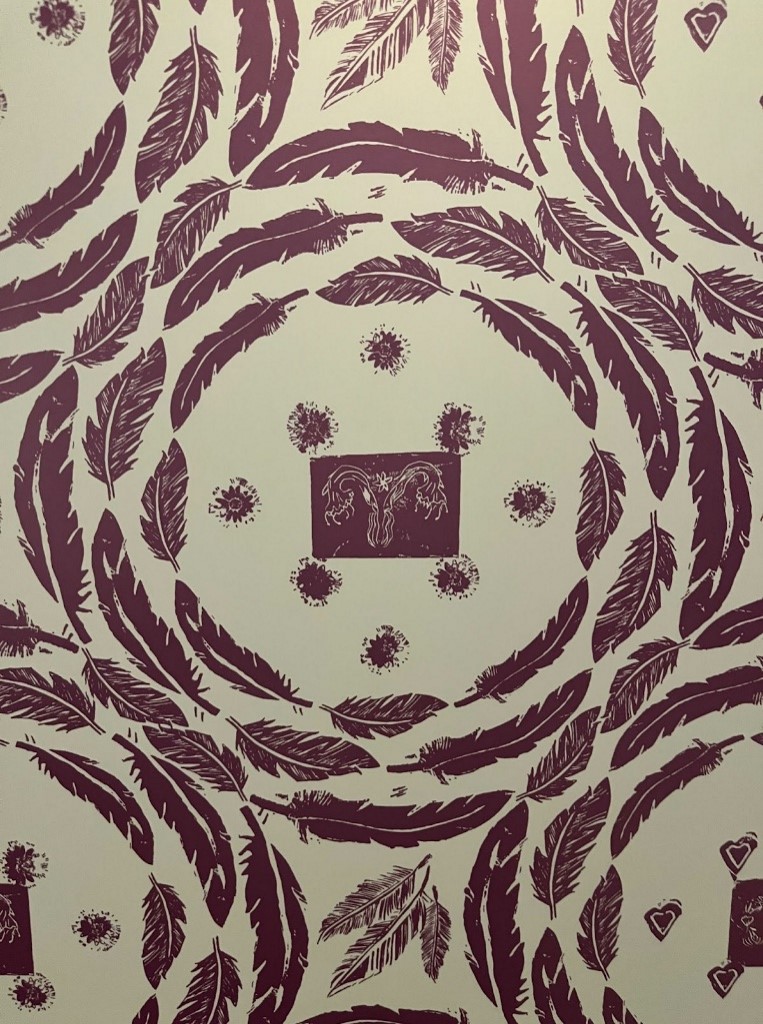

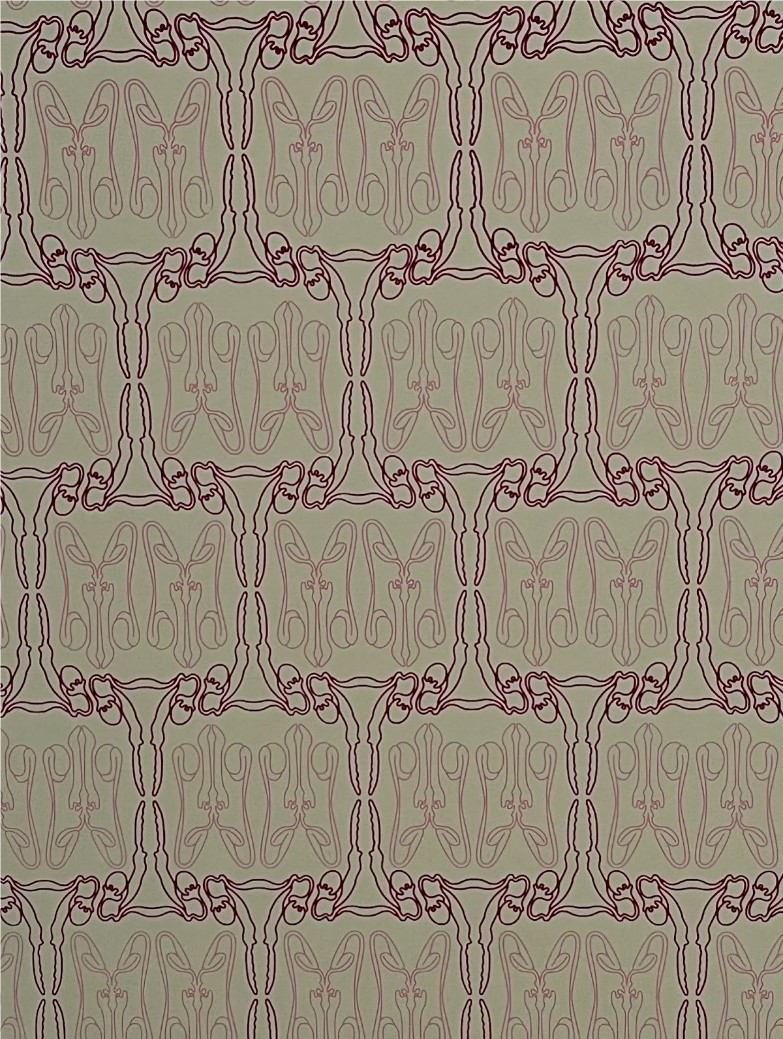

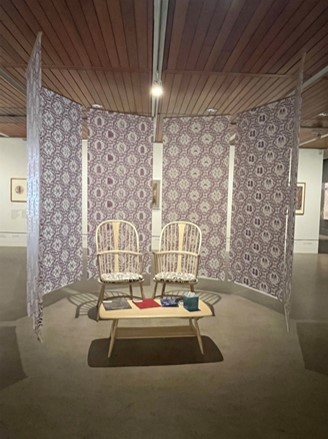

The other two striking features of the exhibition are the reflection space and the relaxation room. Wallpaper surrounds the reflection space, featuring uterus images repeated in symmetric, rhythmic patterns (see Figures 4 and 5).

The relaxation room is a tranquil space for visitors if they are triggered by any of the exhibits and is located behind revolving wooden doors that separate it from the rest of the exhibition.

The relaxation room allowed me private space to meditate on the experience of a woman’s pregnancy. While reflecting on pregnancy, I could think of morning sickness, labour pains, kicks of the baby, and delivery, but not stillbirth or losing a child. Meditating on the experience of bearing the child for nine months in the body, the mother eagerly awaiting the great event – meeting the baby —I thought of the various kinds of pain (physical, emotional, social pressure for some to birth a son, etc.) women experience during the pregnancy, which further get intensified with the traumatic event of stillbirth. It is difficult to cope with a family member’s death. Yet it is much more difficult to cope with the death of a member who is yet to be welcomed into the family.

My conversations with the curators and the participants made me more aware of the role and power of the arts in healing trauma. I also attended the Beautiful Care event, an impactful initiative by The University of Manchester, which included participants from Still Parents. These participants and other curators discussed the impact of the arts in the process of healing and the difficulties of procuring funding for arts projects. Still Parents participants shared that creative arts projects helped them to express their grief. Sometimes both the partners would collaborate to create a pot or a painting. They also shared that making creative artworks helped them contemplate coping mechanisms they could adopt to battle their grief. Moreover, making artwork associated with the loss of one’s baby is making a memory of the child that parents have yet-to-know and it is a creative process. As a doctoral student pursuing medical humanities and especially Care Studies, I wish to acquaint grieving families with the activities of the Still Parents project so that they feel encouraged to visit or know about the artistic care narratives curated at this impactful exhibition that bespeaks a journey of healing.

Swati Joshi is pursuing doctoral studies in medical humanities at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar.