Podcast with Stuart Murray and Amelia DeFalco in conversation with EIC Brandy Schillace

Today we are pleased to speak with Stuart Murray, Professor of Contemporary Literatures and Film, and Amelia DeFalco, Associate Professor of Medical Humanities in the School of English, University of Leeds. We at Medical Humanities have been following a new project they are both working on, LivingBodiesObjects (Twitter: @LBObjects), and today they provide us with some insight into this ground-breaking (and mind-mending) work. We’ll talk about what the term “transhumanism” has come to mean, its social justice implications, and ways that the medical humanities seek to bridge gaps. Transcript follows below!

Dr Amelia DeFalco is the Principal Investigator of Imagining Posthuman Care. Amelia is Associate Professor of Medical Humanities in the School of English, University of Leeds. Her research focuses on contemporary cultural depictions of ageing, vulnerability and care, particularly in relation to technology. She is author of Imagining Care: Responsibility, Dependency, and Canadian Literature (University of Toronto Press, 2016) and Uncanny Subjects: Aging in Contemporary Narrative (Ohio State University Press, 2010), essays on cultural representations of ageing, disability, gender, care, technology and the posthuman, and co-editor of Ethics and Affects in the Fiction of Alice Munro (Palgrave, 2018). She is the Co-I of two Wellcome-funded research projects, Imagining Technologies for Disability Futures and LivingBodiesObjects (beginning January 2022). She is currently writing a monograph, Curious Kin: Fictions of Posthuman Care, and co-editing a Special Issue of Senses and Society on the theme of affective technotouch. @AmeliaDefalco

Stuart Murray is Professor of Contemporary Literatures and Film in the School of English at the University of Leeds, where he is also the Director of the Leeds Centre for Medical Humanities. His research focuses on contemporary cultural depictions of disability and mental health, particularly in relation to technology, cultural theory and ideas of futurity. He has worked extensively with disability communities and is committed to disability inclusion in research. Stuart is the author or editor of 10 books, the most recent being Disability and the Posthuman: Bodies, Technology and Cultural Futures (Liverpool University Press, 2020). In 2008, he was the founding Editor of Liverpool UP’s Representations: Health, Disability, Culture and Society monograph series, and currently he is one of the Editors of Bloomsbury’s new book series Medical and Health Humanities: Critical Interventions and on the Editorial Board of BMJ Medical Humanities. Stuart’s next book, Medical Humanities and Disability Studies: Beyond Disciplines, will be published by Bloomsbury in 2022.

TRANSCRIPT

DR BRANDY SCHILLACE: Hello, and welcome back to the Medical Humanities Podcast. This is Brandy Schillace, and I’m the Editor-in-Chief. And today I have two guests with me, Stuart Murray, who was on before with us to talk about the LivingBodiesObjects Project, and also Amelia DeFalco, both of them in the School of English and also in the Medical Humanities Research Cluster at the University of Leeds. Thank you both for joining me.

DR STUART MURRAY: Thanks very much, Brandy.

DR AMELIA DEFALCO: Hello.

SCHILLACE: Hello! [laughs] Now, Stuart, you’ve been on before, and so, and you’re also on our editorial board here at Medical Humanities. But Amelia, I was wondering if you could introduce yourself as well for those of our listeners who might not be as familiar with your work.

DEFALCO: Sure. So, I’m an Associate Professor in Medical Humanities, as you mentioned, located in the School of English, working mostly on the contemporary, specifically on literature and film, care, and increasingly, the posthuman.

SCHILLACE: That’s fantastic. And Stuart, of course, I’ll have you give a brief introduction just in case people are joining us for the first time and haven’t had a chance to get to know you before.

MURRAY: Thanks. So, I’m Stuart Murray, and I work in many of the same areas as Amelia. Actually, we find ourselves in a lot of meetings and conversations together. So, I work particularly on depictions, representations of disability, and increasingly, on the technologized body and posthumanism.

SCHILLACE: Yes, that’s fantastic. And of course, I know what posthumanism is, and I’ve been really interested in it for a long time, particularly from the, you know, through the lens of Disability Studies. But I was wondering if you could say a few words to those in our audience who might not be familiar with posthumanism. What does it really mean when we talk about this?

MURRAY: Ooh. Do you wanna go first, Amelia?

ALL: [laugh]

DEFALCO: Well, the…. I guess one thing to keep in mind is that there are many posthumanisms, so it can be used to signify a wide range of approaches to embodiment, longevity, technology, and the more-than-human world. The way that I, the aspect of posthumanism that I’m interested in, which is often referred to as critical posthumanism—often to kind of differentiate from the more kind of transhumanist area, which embraces body modification as a kind of way to elude vulnerability—that the critical posthuman perspective is helpful for me for thinking about well, the shorthand is often in decentering the human in theories of living and being and knowing. But it also foregrounds embodiment, embeddedness, the connections between, and the not just interconnections, but intra-connections. And those are the areas that I’m particularly interested in, the degree to which an incredible array of bodies, human and more-than, are inevitably connected and entangled is the favored word of posthumanism.

SCHILLACE: Right, right. Well, because I think a lot of, one of the things that is true is that humanism, obviously, kind of gives it away, right? Humanism makes human the center of the world, center of everything. It’s very, it’s a kind of well, it’s not dissimilar, in fact, of the way that things were looked at in the 19th century, right? The human is the top, it’s the best thing ever, and that’s what we focus on. Of course, the downside of moving away from humanism is the fear that we will, that the people who are already disenfranchized will then become less centered than they already are. And so, I think it’s interesting to say posthumanism and transhumanism isn’t saying humans don’t matter. It’s almost the opposite. It’s saying that we need to center all human beings in their relationships to the world, to the environment, to each other, to technology, to society, to all the things that we’re part of. Would you say that that’s kind of an important differentiation to make?

DEFALCO: Absolutely. I think that’s a key point, because there are many ways that posthumanism can potentially, can be alienating for, as you say, for modes of activism that are looking to increase inclusion. Because if it, if there is this sense of moving towards what some have called this horizontalizing of the ontological plane, right, where there’s, you’re kind of moving away any kind, from hierarchy to the point where there’s no, the anthropocentricism is completely discarded, then what happens to those efforts, right—

SCHILLACE: Right.

DEFALCO: —for inclusion if there’s no longer any human? But I think some of the most exciting work happening in posthumanism, whether it’s kind of termed posthumanism or not, is the work of Black and Indigenous scholars who are, you know, have been interrogating the very idea of the human and demonstrating the degree to which it’s always been a exclusionary construct and one—

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm. White, Western.

DEFALCO: Yeah. And one that, I think a lot of them suggest, can’t really be rehabilitated. So, we have to find other modes of thinking.

SCHILLACE: Right. And one of the things that, one of the criticisms I’ve heard leveled at posthumanism is, well, don’t we already have a society that says material objects are more important than people, that money is more important than people? That, you know, why do we want to promote something which suggests somehow, you’re taking humans out of the equation again? And so, I think that’s why I’m leaning on this, and I’d love to hear you say a few words about this, Stuart, about when you’re, when, in fact, it can be a really a good way of honoring these systems and saying, no, we are not, in fact, saying somehow people don’t matter, but rather almost the opposite.

MURRAY: Yes, because I think like Amelia, I would’ve immediately gone for the word the “decentering” as part of understanding posthumanism’s critical practice. And what I think is so effective there, then, is precisely the kind of assemblages and networks—which are two other big posthumanist phrases—that can be built as a consequence of thinking through that decentering. And that’s where I think posthumanism and the Medical Humanities is so interesting and posthumanism and medicine and health more generally. Because if you look back to early models of the Medical Humanities, where much of the reason given for the involvement of history, of art as therapy, or ethics was precisely this idea that those subjects humanized what was otherwise a process of medical science.

And I feel that there’s been great profit in using those decentering practices to think about, for example, how ideas of wholeness were constructed around the body, and not just the body. Ideas of wholeness were constructed around the physician, say. So, the idea that there was a singular physician looking at a singular patient and trying to think of their body in terms of restitution or recovery as the primary outcome of health. I think that the critical turn in lots of subjects, whether that be Medical Humanities or posthumanism or something analogous like Animal Studies, I think that’s done great work, particularly in our subject, particularly for helping us to understand what we might think of as cultures of health, yeah. Interconnectedness, human animals, non-human animals. So, I absolutely get the points about suspicion. I think there can be a real problem, as Amelia says, in making an assumption that you can just jump away, I think in particular, from structures and communities of vulnerable populations. So, I think it’s a balance then between working out the incredible effectiveness of the decentering practices, but not being so lost in abstraction that you leave behind the people you would want to talk most about.

SCHILLACE: I think that maybe one of the issues for me is I don’t think it needs to be so much about decentering the human as decentering the center. The center that has always been, which tends to be White and Western and frequently masculine, is what I think is valuable to decenter or to queer, as it sometimes posited. This idea that you can pitch back at wholeness, using wholeness as a word. I think this is great in the concept, or I’m sorry, in the landscape of Disability Studies. What does it mean to be whole?

So, for instance, I was just on a, helping with a book tour. Lindsey Fitzharris just wrote a book called The Facemaker about plastic surgery in World War I. And one of the tensions that she discovered in that book and that I think is really fascinating is the difference between arriving at functionality—so, you’ve been injured, you’ve had your jaw blown off or something—arriving at functionality versus continuing for another 30 surgeries to try and arrive at a space where you think you are whole enough for society. And this concept that you can’t return to society unless you achieve a kind of normative wholeness, right? And this was difficult for soldiers who lose limbs or other amputees. But it also, I think, people who are in wheelchairs, they don’t consider themselves not whole. [chuckles] But yet medicine, as you point out, has a tendency to center on this idea of the whole, perfect human in ways that’s really problematic and, in fact, stigmatizes and causes all kinds of other problems.

MURRAY: So, really good example of the First World War, I think. And to take up the point you rightly make, it’s not entirely about decentering the human because it’s about decentering structures as much as anything, isn’t it?

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

MURRAY: And I think there’s been great writing from historians on disability in the First World War. I think of the work of somebody like Julie Anderson. And what’s so effective there is not just to see how medical practices followed this idea of a stress on a recovery of wholeness, but how that equally was built into governments and state policies of public health.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, mmhmm.

MURRAY: And when those things come into play, you’re absolutely right, Brandy. It’s the point, isn’t it, about, you know, those are not structures of the human per se. Those are structures of governance and structures and systems of health care. So, I think when we track that back to what we mean by posthumanism, it’s carrying forward a critical impetus of the positive offsetting, I think: what we can see positively from those processes, and certainly, the intersections between them and Medical Humanities. I think what Amelia and I would say working on the project as we are, LivingBodiesObjects, is that we’re not over-focusing on the posthuman, but it’s definitely something which is making the approach of the project. You know, it’s giving it insight.

SCHILLACE: Right, right. Well, and let’s return then to LivingBodiesObjects, which is in process. This is something that’s really unique in the sense that we’re not waiting until you have a thing, but rather, we’re investigating and engaging as you create and come up with and dig and do all of the things around that project. So, could you tell us a little bit about the launch, about where you are, about where you’re headed, and where we are in this particular space of time?

MURRAY: Sure. We had the launch last month, and it was wonderful. And it was wonderful for lots of reasons. And I was thinking back to the conversation I had with you, Brandy, before we had the launch, because we were talking a lot about ideas of research, how it started, why it started, what you took for granted, and all those things that are aligned with that. And so, one of the things that we’ve been doing for many months was talking in those open terms. We talked about the whole idea of pausing before you start.

But with the launch, of course, we were tasked with lots of people coming to see things that we had made and for us to be able to articulate why we had made these things to showcase the project and in order to engage with our audience. So, what was one of the, I think, really powerful things about it was the way in which we felt challenged to turn our thinking into making and to come up with a set of exhibits, which is precisely what we did, that we could point to, if you like, and say to the audience, “Go touch these, go engage with these, and you will see what it is that we’re trying to do.” And so, I think for the whole team, that challenge was very, very meaningful in the questions that it asked of us about putting into practice, putting into making, the whole ideas about living and bodies and object and research systems that we’ve been talking about for three months or so.

SCHILLACE: Hmm. Mmhmm. Yeah, I can see that. And Amelia, how, I mean, this is actually really fascinating to me how once we put those, all those words together, right—”living, bodies, objects”—it elucidates sort of what you were saying about why we might want to use a posthuman or transhuman lens or a decentered lens as we approach a project like this. Because, of course, research projects tend to have a certain kind of expected center that is unfortunately the same kinds of centering on White and Western ideas. And so, do you wanna say a bit about that? Because I feel like there’s ways in which this project and posthumanism could potentially have deep value for social justice. And of course, Medical Humanities as a journal is a social justice journal. So, can you tell a little bit about that and about your experiences of that?

DEFALCO: I’ll try. [laughs] So—

SCHILLACE: Sorry. That was like three questions. I’m sorry. [laughs]

DEFALCO: Well, I mean, I’ve been listening and just reflecting on what you were saying earlier, Brandy, and the way that Stuart responded. And just, I wonder, I mean, in some ways, I guess what I was going to say about the project maybe links back to what you were saying earlier about kind of questioning the degree to which this idea, the decentering of the human, is something, is consistently what the posthuman is about or should or wants to be about. But I wonder, in that case, if it’s kind of helpful to think about “the human,” in quotation marks for the entire phrase in the article there being so important. And it has to do with the notion of singularity, not “the singularity,” but the idea of the human as a kind of identifiable, singular entity, right?

SCHILLACE: Mm, mmhmm.

DEFALCO: And the degree to which—

SCHILLACE: And a whole, you know, and a whole idea, at that, right? Yeah.

DEFALCO: A whole. And as…and which, as you rightly point out, is, you know, it tends to be racialized, gendered, etc., in a very particular way, right, that we’re all very familiar with. So, I think for me, that’s a part of the posthuman that’s integral, right? Is the interrogation of the human as a singular, as a discrete, as kind of, and thinking, as Stuart was saying about networks, assemblages, but also, and ecologies, right? The degree to which there’s a kind of constant connection that requires addressing or acknowledgment and the degree to which there’s a real loss when one focuses on, say, dyads or triads, the kind of, like the doctor-patient relationship, for example, that Stuart was talking about is a place to start, but the entire structure and the entire kind of larger ecology has to be taken into account.

SCHILLACE: Yeah.

DEFALCO: And so, coming back to our project, I think the fact that the words, you know, we’re not using articles, but also, if you see the way that we’ve written it, there are no spaces between the terms.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

DEFALCO: I think it’s partly getting at the idea of kind of that kind of mesh and entanglement and the degree to which LivingBodiesObjects is as much a kind of interr-, a kind of question or interrogation as a statement. And thinking about the degree to which these blur and blend and can’t always be differentiated and how we might investigate that. And as Stuart said, it’s an unusual project in how open-ended it is, and which is incredibly liberating and exciting. And it also can be very daunting.

SCHILLACE: I was gonna say overwhelming, maybe.

DEFALCO and SCHILLACE: [chuckle]

DEFALCO: Yeah, it really can be, but in a very positive way. But it feels, you know, there is a kind of potential limitlessness that’s, you know, many people talk about how useful boundaries are or limits are for kind of creative practice, right? Having to kind of come up with creative solutions to barriers or boundaries or limitations. And in this case, the openness is perhaps one of the biggest challenges.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

DEFALCO: But we are very lucky in being, in having such a diverse team in terms of disciplines, but also that includes a creative facilitator. And soon we’ll have a staff member devoted to documentation. So, there’s a kind of range of skill sets and experiences, and that’s been, for me, the most exciting thing so far is that we’re kind of being pushed into areas that we, that speaker of myself [laughs], I’m not as comfortable with initially, but have been incredibly illuminating for thinking about the topic, making things together, imagining kind of material, the way the material world might address some of the topics that we want to consider. And then putting something together and then seeing it as a thing, as a living thing was incredibly satisfying.

SCHILLACE: I’m really—

MURRAY: Brandy?

SCHILLACE: Yeah, go ahead.

MURRAY: Oh no, I was just gonna, if it’s okay, I was gonna pick up on one of the, one of your comments about social justice, if I can. Yeah?

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

MURRAY: Because I remember after you and I last talked, I took away a set of ideas around justice as you were framing it and as I know that the journal frames it. And one of the things I was thinking of post-our launch was, well, when something might be overwhelming or when it’s open ended, how can that be a vehicle for justice, in the sense of it maybe not having the kind of boundaries that Amelia was talking about, the kind of materiality? And I was thinking back to the actual things we did in the launch, the things that we made.

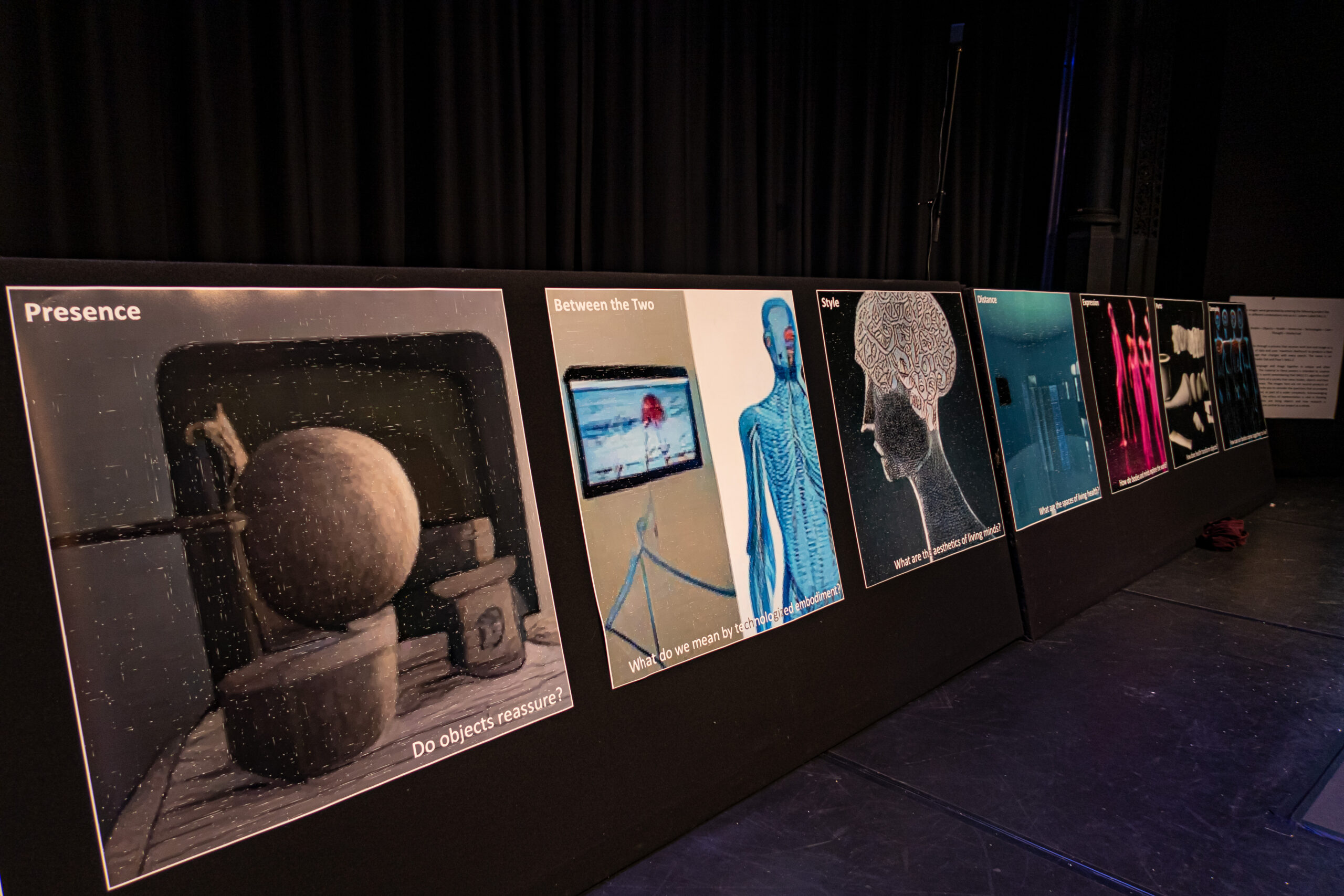

So, we have some mannequins and some body parts, for example, and we projected images on them of viruses and of living organisms. We had posters that were produced by putting the keywords from our project title into a AI generator. We had a series of physical objects that were mounted as if they were in an exhibition. And all of them, we came to realize, were provocations.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

MURRAY: And I think there was something in the way that we were not just asking, as it were, basic questions of our audience, that we were provoking them to think about these three key words. And I thought, well, yeah, this is connected. This can be connected to an idea of justice because the invitation to interrogate and to reflect, I think, can be a platform for the kind of justice within Medical Humanities work that I think we would want to happen.

So, even if there is this hard work that needs to come with the open-ended-ness of the project, we get moments like that where you realize that the provocations you’re making do become this space in which ideas and questions of justice, from which those questions might flow.

SCHILLACE: I think that that’s, and actually, what I was gonna tag back to something Amelia said that now actually connects well with what you’ve just said. So, you set this up for me brilliantly! But I love the concept of questioning quote-unquote “the human,” Amelia. And I think, I used to work in a museum, so I worked in a medical museum. I did do exhibits, and I know the Wellcome Collection has its share of exhibits. And all the time when you’re curating, you’re setting yourself up to be like, “I’m telling you what’s important,” right? “This is ‘the’ history of ‘the’ human in ‘the’ medicine.” And so, I think interrogating that and breaking that down is hugely important. So, if you created an exhibit where the people who see the exhibit get to go, “No, that doesn’t mean that to me,” [laughs] or “I have questions” or “I think you should take this in another direction” now, we’re creating a space that is very different, that is doing a very different kind of work, that’s asking people to create with you in this experiential space. And I think that’s, I didn’t get a chance to go to your launch or to the exhibit, as I was not in the right country, but—[laughs] it makes it difficult—but I do think that that’s really a powerful thing. If you can invite people in to be part of that process, that in itself is opening a door to social justice because of course, it’s what I always say at the journal that we want to speak with, not about. I wanna hear from, not talk at, not hear about. So, when you’re inclusive in that way, and open ended in that way, I think it creates spaces for new things to happen. And in that sense, I love the idea that what we’re really doing is saying, “What is ‘the’ human, what is ‘the’ history, what is ‘the’ medicine?”

DEFALCO: [chuckles] Well, I was thinking something really similar, Brandy, because one of the elements of the launch, one of the installations, as Stuart mentioned was a series of objects that were kind of displayed in a similar style to a museum exhibition. And I had recently developed an exhibition at our local Thackray Museum of Medicine here, and it was a really interesting experience to do the two back-to-back. Whereas with, as you say, working with the museum, I felt really tasked to tell the story, to tell, to at least explore a narrative, to develop a narrative that had a kind of consistency to it. In this case, what we did was create, include objects that had multiple potentially conflicting placards associated with them.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm, mmhmm.

DEFALCO: And so, depending on your approach, you would get a different version, and then you could go around them and kind of chart your own response in relation to these. And some were quotations, some were descriptions and that were more or less obviously explicitly stemming from the object. So, using that one instance, there was a really clear sense of what was really different about what we were doing and the degree to which the project has facilitated a different kind of, a different mode of working than I’d ever had the opportunity to explore before.

SCHILLACE: Right.

DEFALCO: So, I think it was very fortuitous that they were back-to-back [chuckles] ‘cause I mean, it was the first time I’d ever put an exhibition together in a museum. Prior to the launch anyway, I wouldn’t have had that to compare it to. And then recently, the group, part of the LBO group, Stuart wasn’t able to come, but we went to London last week to go to the Wellcome, and that was also a good reminder of the varied ways that an exhibition can tell stories and the way that within an exhibition itself there can be a kind of dialogue, a kind of speaking back to the conventions of display. So, I think, yeah, I think that’s something we wanna carry forward as we continue.

SCHILLACE: Yeah. Digital displays, actually, when I worked on an NIH-funded project, a big one at a museum in which we developed a digital project so that you could actually build your own narrative through it. You could almost give your own, take yourself through the museum in the ways that you wanted to. But, and obviously, there’s limits to that, too. But I think increasingly, especially with this new virtual world in which we live, post-COVID, that there’s some expectation that there’s gonna be abilities to engage, right? That we’re looking for point and click options that you might not have originally had those expectations. So, it’s a good time for a project like this. Though I will say I’ve had people ask me, “So, what is their project?”

DEFALCO: [laughs]

SCHILLACE: And I do find answering that question is somewhat complex. I’m like, “Well, it’s about being about things.”

DEFALCO and SCHILLACE: [laugh]

SCHILLACE: But that is part of the joy of the project, too. Did you wanna say a bit more about that specifically? Stuart, I know that we grappled with this some the last time, and I figure at each stage you’re gonna know a little bit more about where you’re headed.

MURRAY: I think so. I mean, it’s true. A slight anecdote, but when we were successful getting the funding for the grant, the university press office said they’d like to release a statement about it. And they asked us what the project was about, in a very press office type way. You know, they needed a hook, and they needed to be saying, well, who benefits from this and in what way? And we had this rather problematic back and forth about me not being able to supply them with the kind of taglines that they wanted.

I think that you described it very well, actually, about the about. But one of the things that the launch did was definitely make some of that more concrete. I mean, because listening to what you’re saying and you not knowing the details of it, you’re nevertheless talking about things we did.

SCHILLACE: [chuckles]

MURRAY: So, we did have a VR experience. We did have an incredible amount of kind of digital input. We had a dancer who danced to body sounds, who was dancing to a heartbeat of one of our team members. And then when she danced faster, the heartbeat increased. And whilst that is a certain amount of playfulness, it’s also going back to those points we’re trying to make about how bodies operate in the world. So, I guess what we feel is that we’ve put together four or five months in which we’ve kind of done a deep dive, not just into some foundational ideas of bodies and objects and the whole idea of living, but how you do the research on them.

And the next phase is to start working with specific partners to kind of both continue and develop that. So, from July, we’ll be working with a theatre company in Leeds called Interplay Theatre, who work a lot around sensory theatre, and we’re really excited about the kind of dynamics that are going to emerge from that. But we’re still being guided by that kind of openness. You know, we’ve had initial conversations with them, and we want to go where they want to take us, in many ways. But we’ve got a set up now. We know how that can start. We can build on what we’ve done. So, we are finding out about it.

But I think the fact we made things that really spoke of our work has been incredibly enabling because I’m sure we’ll be able to provide you with some of the photographs of what we did.

SCHILLACE: Yeah, I’d love that.

MURRAY: And hopefully, they can go with, you know, when you put this podcast on the site. And that will give people listening now a sense of what we’re doing. And the website is only, is not very far away, I was told today as well, actually.

SCHILLACE: That’s good.

MURRAY: So, that’s gonna be really great.

SCHILLACE: Well, don’t you think in some ways, I mean, you’ve made things with your bodies. I mean, that’s, it’s a very different thing from coming up with an idea in your mind. And I think there’s a tactile and haptic response that goes into creation of that sort. And so, I’m not at all surprised that it had those kinds of outcomes for you, but also that that’s what this project is trying to get at the heart of.

I will say two things. One, absolutely, we will include images, and we also do a transcript of all of our podcasts, so that’ll be available as well on the blog that’s attendant. But two, doctor, sorry, the Medical Humanities project, as a journal, is also attempting to grapple with those questions. How do you research? How do you, if research itself has structures that you need to get around, how do you research, how to do research [laughs] when you’re coming from this? It’s sort of like trying to see the back of your own head.

But we’re doing something like that at the Medical Humanities Journal as well, which is there’s huge problems with the fact that publishing as an industry, and academic publishing in particular, is exclusionary by its very nature. It’s hard to get in. It’s hard to, there’s paywalls, even, and there’s paywalls whether it’s open access or not. It’s either at the user end or at the producer end. So, you’re either paying to open it as an author, or you’re paying to access it as a reader. And that means that we’re not hearing all of the voices, and it is very difficult. How do you get into press? How do you? You can say all day that you want diversity in publication, but how do you actually make that happen? So, we’re having to deconstruct and work around what the, what publishing normally looks like, and that’s partly why we’re doing path to publication now, which works with people from the Global South. But also, we’re having an issue on neurodiversity written entirely by neurodiverse people, and we’re taking that through this two-year process in order to get them in a place where they can publish. Because you almost have to deconstruct the very nature of what you do in order to achieve the ends that you want for the purposes of diversity.

So, I wanna just ask one last question, and then I’ll let you guys go. I really appreciate your time. And that’s this. Even though at the moment you’re still working out exactly what these research questions will be, what do you hope that the outcomes are? What are your larger goals for opening up these kinds of conversations? What do you hope will achieve by doing a project like this?

MURRAY: Just for my part, I will say that it’s not all about kind of gazing towards the horizon in which anything is possible. I mean, my hopes are that at the end of the three years, in many ways, we will have got a kind of critical methodology that we can then turn to, or turn into rather, research questions. That there will be some element of health experience, some kind of dynamic of health that suddenly, we realize we have critical tools to discuss.

SCHILLACE: Mm, mmhmm.

MURRAY: And they hopefully will be not just about research and publication or about research that takes different forms but will be able to look at whatever they are, those texts, those oral histories, those kind of, you know, different kinds of manifestations of health. And we’ll be able to say, because we’ve done what we’ve done, we can now do, if you like, phase two. We can now look towards taking forward this methodology. So, that’s on the one hand. The other thing is that we hope we can then turn round and face our university and say, “Well, look. You can do research in this way. You can include these people. You don’t have to abide by these metrics. Or maybe you do. I don’t know,” you know.

SCHILLACE: [chuckles]

MURRAY: But you can have a research environment which doesn’t have to simply perpetuate current dynamics, which is, as you said very eloquently that are frequently exclusionary.

SCHILLACE: Exactly. So, I think that this is a really brilliant way for you guys, the way you’re opening this up. And I’m really excited that Medical Humanities as the podcast can be part of this and that we can keep having these conversations. So, if you’re just listening to this podcast for the first time, we had Stuart on before, and we will be having additional ones in the future. There will be other colleagues, other colleagues of Amelia and Stuart, that will take part and tell us more about this experience as it moves forward into the future of what it’s going to produce and how. So, thank you both for being on here. I really do appreciate your time. And I know everyone here has really enjoyed listening to you. Anything to leave us with?

DEFALCO: Well, I’m very excited, as Stuart mentioned, for the website to, [chuckles] to happen, so that we have a place where we can collect and share all of these various outputs, which are for me, for me anyway, rather unconventional outputs.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

DEFALCO: You know, I’m pretty accustomed to the more conventional kind of text-based work that you would find in journals and books. But the way that we’re incorporating a degree of kind of embodied practice has been really exciting for me. And finding ways to make those available is part of the challenge of the project, and the website will be the first port of call for that. You can follow us on our Twitter, which Stuart knows. [laughs] Sorry, Stuart.

SCHILLACE: [laughs]

MURRAY: It’s @LBObjects.

DEFALCO: @LBObjects. And these are all kind of, I have to admit, quite nascent, you know. They’re just coming into maturity soon we hope. But because we’ve spent so much time really focusing on what ended up being called, I believe, the start before the start was our first period.

SCHILLACE: Yes. [chuckles]

DEFALCO: So, we were focusing on our group as opposed to outward facing.

SCHILLACE: Which is again, super, super awesome and not done nearly enough. I think that’s, it’s fascinating. It’s a project that’s decentering the center, but it’s also at the same time really centering on the people that are part of it. I think it’s really brilliant.

DEFALCO: Well, it’s been, I have to say, it’s been a delight so far. And then as we work with Interplay, as Stuart mentioned, there will be, certainly be events happening that will be posted on that website that will be, some of which will likely be open to the public.

SCHILLACE: Mmhmm.

DEFALCO: So, please do stay posted if you’re in the Leeds area, in the Yorkshire area. But we’re also going to have all kinds of really wild and wonderful forms of documentation [laughs] available.

SCHILLACE: Yes.

DEFALCO: So, I would say, from now till the end of the year, things will be emerging quite rapidly.

SCHILLACE: That’s fantastic. That’s fantastic. Well, I just appreciate having both of you on. Listeners, please tune in again, and thank you, as always, for being part of the conversation.