Blog by Sarah E. Rowan, Michelle Haas, Lilia Cervantes, Kellie Hawkins, Lilian Barahona Vargas, David Duarte-Corado, Alonzo Ryan and Carlos Franco-Paredes

Days ago, a clinician in Denver looked with anger at a patient who laid dying in the ICU. “Why didn’t she access care earlier? There are resources available and now she’s dying!” The patient was the mother of two young children, and, as it turned out, undocumented. The risk of engaging with any type of program and being separated from her kids was likely too great for her.

The Covid-19 pandemic wrenches our fault lines wide open and exposes our inequities to the open air. In nearly every case with full hospitals, student learning loss, shuttered businesses, and overextended frontline workers, the harm of the pandemic exacts the greatest toll on communities of color and lower-income individuals. Federal, state, and local governments initially appeared helpless. In many cases where disparate impacts went unchecked, it was not for lack of good and willing officials on the ground, but rather for want of a clearly articulated and conspicuously stated vision of their roles—a north star.

Justice as our true north

We need guiding principles to drive our actions. As we tread through our emergency responses and tackle rebuilding, the identification of our communities’ “true north” will lead to activities that are more thoughtful, coordinated, focused, meaningful, and durable. Equity is a pillar of social justice that we must uphold; equity elevates fairness. Thus, equity is the most effective way to remediate unfair social arrangements, seeking to eliminate disparities and start repairing damage done. Equality alone perpetuates the system that upholds white supremacy and will prolong the pandemic by shunting resources away from communities with the highest COVID-19 burdens.

“The fierce urgency of now”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of “the fierce urgency of now” as a rebuke to the “tranquilizing drug of gradualism” that had permeated the changes driven by the civil rights movement. In particular, school desegregation was progressing slowly under the clause of “all deliberate speed” in the second Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

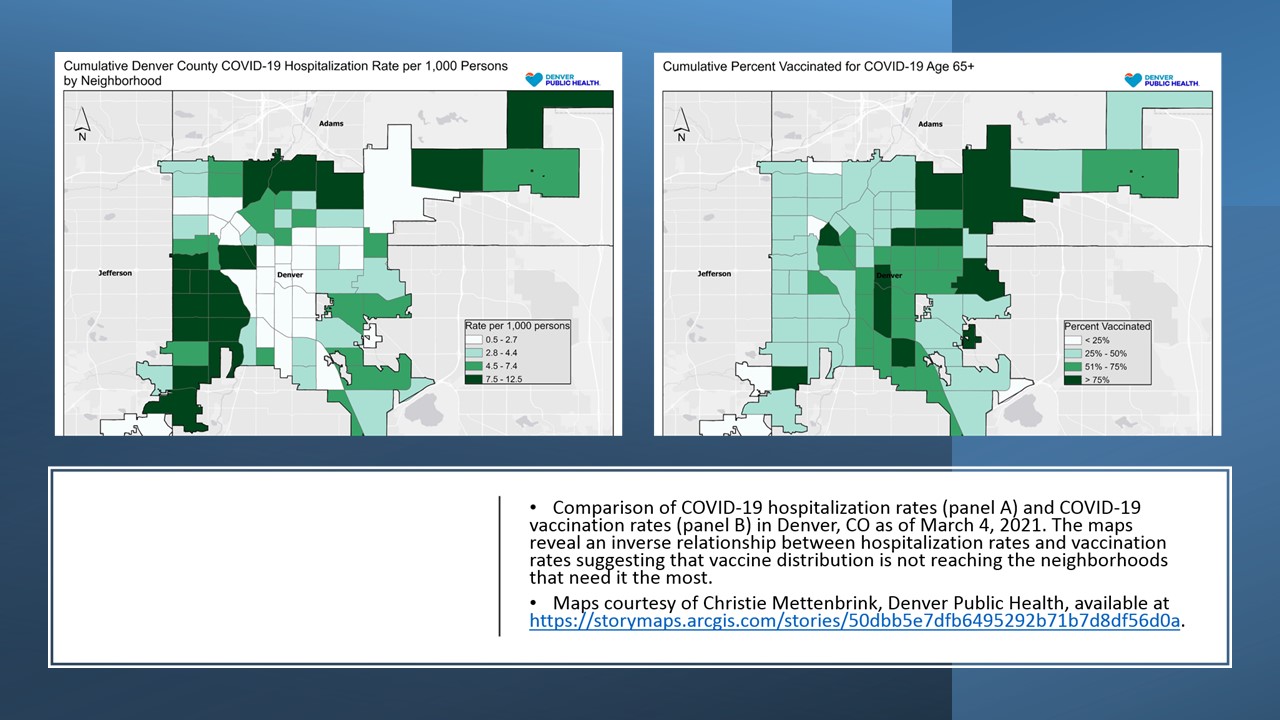

In the spring of 2020, communities struggled to devise emergency response plans. In many cases, approaches were “well-intentioned, well-designed, but with a sense of moral equivocation at a crucial moment,” to apply Charles Ogletree’s observation of the post-Brown era. When healthcare resources became scarce, our systems—and the policymakers acting within them—acted without an equity framework, a north star, leading to disparities in Covid-19 testing, hospitalizations, and death. It is not too late to act with fierce urgency toward vaccine distribution. Before more lives are damaged, our society must agree that social justice is our true north and work quickly to ensure that Covid-19 vaccine distribution is equity-focused.

Defining an equity framework

Leading with equity means sending resources where they’re needed rather than giving everyone equal slices of pie, regardless of how much pie they already have. A better analogy is that of a firetruck going to where the fire is rather than spending equal time on every city block. Vaccines, testing, and support services need to be in neighborhoods where Covid-19 has caused the most harm.

Leading with equity also means prioritizing those who are least able to advocate for themselves. This includes those experiencing homelessness or incarceration, or children, and intentionally reaching out to politically disenfranchised communities. These may be immigrant or those communities still reeling from the lingering toll left by redlining.

Social marginalization versus individual risk

Societal imbalances rooted in policies that reinforce inequitable access to power, opportunities, and resources are being magnified during the deployment of COVID-19 vaccines nationwide. Age-based vaccination policies ignore the social radiograph driving COVID-19 morbidity. Disparate prevalence is the result of food and housing insecurity, discrimination, multigenerational households, and insufficient information. Vaccination strategies that target socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals will reduce social inequity and interrupt community transmission. It is clear that prioritizing racial justice will help all communities to prosper.

A call to action

The following actions would improve equity in the Covid-19 response, ultimately leading to better outcomes for everyone.

- Use of data to track disparate effects of the pandemic and efficacy of the public health responses

- Ensuring that testing and vaccines are free and easily accessible

- Distribution of information in many languages and through multiple modalities: phone, internet, mail, and in-person

- Partnering with community organizations to provide what communities need to thrive

- Consideration of whether an action will improve or worsen racial disparities

- Prioritization of vaccines for communities hardest hit by the pandemic to expedite their medical and economic recoveries

- Responding to vaccine hesitancy with truth and not blaming hesitancy for the disparities that have arisen from lack of access

- Provision of medical and financial support for those who are sick so they can isolate safely

And finally, we must address the underlying structural forces that created the glaring social disparities of the Covid-19 pandemic. We must not go complacently back to systems that allow for preventable deaths of young mothers, or anyone.

Sarah E. Rowan is an Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Colorado and the Associate Director of HIV and Viral Hepatitis Prevention at Denver Public Health where she leads public health preventive efforts and health equity initiatives.

Michelle Haas is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Colorado and who oversees the care of people with tuberculosis in Denver, Colorado and directs the COVID-19 Enhanced Patient Support program which aims to empower communities most impacted by COVID with free medical care, connections to resources and trusted health information.

Lilia Cervantes is an Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado. Her research focuses on access to care for underserved populations.

Kellie Hawkins is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Colorado who cares for structurally marginalized populations at Denver Health Medical Center

Lilian Barahona Vargas is an Infectious diseases fellow at the University of Colorado who provides medical care to underserved populations in Denver Colorado.

David Duarte-Corado is first year medical student at the University of Colorado, School of Medicine

Alonzo Ryan is a second-year internal medicine resident at the University of Colorado, School of Medicine

Carlos Franco-Paredes is an Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Colorado who currently works in decarceration efforts along with civil right attorneys and advocacy groups