Review by Neil Singh, a primary care physician and senior teaching fellow in the Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Brighton and Sussex Medical School

‘Cooked: Survival by Zip Code’ (Judith Helfand, USA, 2018, distributed by Bullfrog Films) (Streaming free on PBS, also available on Amazon)

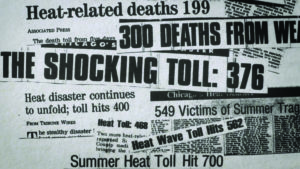

“What’s the best way to prepare for disaster?”, Judith Helfand asks, in the opening scene of this important, independent documentary film. Helfand’s probing film focuses on the record-breaking 1995 Chicago heatwave as a case study. I have always pictured heatwaves at the shallow-end of natural disasters. I was wrong. Heatwaves kill more Americans than all other natural disasters combined. And the 1995 Chicago heatwave was one of the worst. Between July 13 and July 20 1995, bursting thermometers recorded a high of over 52 degrees Celsius, streets had literally melted and buckled, and 739 people had died (1). A tragedy, no doubt, but surely nobody could be blamed for such a freak weather event?

“What’s the best way to prepare for disaster?”, Judith Helfand asks, in the opening scene of this important, independent documentary film. Helfand’s probing film focuses on the record-breaking 1995 Chicago heatwave as a case study. I have always pictured heatwaves at the shallow-end of natural disasters. I was wrong. Heatwaves kill more Americans than all other natural disasters combined. And the 1995 Chicago heatwave was one of the worst. Between July 13 and July 20 1995, bursting thermometers recorded a high of over 52 degrees Celsius, streets had literally melted and buckled, and 739 people had died (1). A tragedy, no doubt, but surely nobody could be blamed for such a freak weather event?

This film—inspired by Eric Klinenberg’s 2002 book, “Heatwave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago” (2) will make you rethink your answer to this question. It drills down into the events of that dizzyingly hot week to reveal sobering lessons about just how ‘natural’ those deaths were. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the deaths were not distributed evenly across the city. Rather, we see how deprivation, race, crime, and sickness became mutually reinforcing curses piled on the south and west of Chicago communities.

We first meet the granddaughter of Alberta Washingtonn elderly black woman who was found dead by paramedics in her small apartment. Like many residents in her deprived neighbourhood that is notorious for drugs and crime, she had her windows nailed shut for security. She, similar to dozens of others who died of heatstroke that night, decided to stay safe rather than stay cool. Air-conditioning units are laughably unaffordable to tenants in this part of town, and there are no safe public parks or communal meeting spaces to shelter from the heat. It is painful to watch footage of bodies lined up, like logs, in refrigerated trucks, finally getting in death what they could not get in life: cool air.

Many of Helfand’s interviewees offer words of wisdom on what happened that week in Chicago. “It’s about a lack of compassion,” one Church elder tells Helfand. “It’s not really about the heat.” Chicago’s chief epidemiologist at the time, Steve Whitman, describes his attempts—discredited by politicians—to reveal the true number of people who had died. His team calculated the death rate that July to be 40% higher than an average year. ‘’But never would the word ‘heat’ appear anywhere on the death certificate”, Whitman explains. In a sense, ‘heat’ too would be an inaccurate summation; by analysing the impact of poverty on the deaths rate, one realises that communities that suffered the most deaths also had the greatest burden of other preventable deaths, regardless of the temperature. As Whitman puts it, one way or another, “they would have died too soon anyway.”

The film challenges the then-Mayor Richard Daley’s description of heat-stroke fatalities as “non-violent deaths”, urging us instead to see this loss of life as part of a bigger story of structural violence against communities of colour. The way society is set up, including the solutions and policies devised to address such problems, systematically disadvantage those who are already most disadvantaged. We see how white speculators buy homes, and then sell them at extortionate prices to black families who are then unable to maintain their homes and often get evicted—literally drawing red lines around black communities, creating ghettos of poverty, which was a contributory factor in the excess deaths. Little has changed in the century since Upton Sinclair wrote “The Jungle”, also set in Chicago, which narrates how vulnerable migrants became victims of such “contract buying” (3).

So, we watch in disbelief as a Chief Environmental Officer unveils his pet-project to cool the city: roof gardens, like the one on city hall. It shows how detached policymakers often are from the daily realities of deprived communities. “We’re pretty far from city hall,” notes Orrin Williams, a dread-locked community organiser in Englewood, as he drives through a boarded-up neighbourhood in the south of the city. “I don’t know about any rooftop gardens around here.”

Helfand visits a disaster preparedness convention, only to find that the priorities, and even the very definition of disaster, is totally unfit to meet the needs of communities like those in the Chicago south side. As we reflect on the affliction of deprived communities ravaged by the coronavirus worldwide, this film reminds us of a hauntingly familiar situation. We need to change our definition of both disaster (to include socially-patterned deprivation) and preparedness (to deploy ample resources of rich nations towards education, health, and broader social goods) if we are to respond better to the next society-wide catastrophe in a way that leaves no community behind.

References:

- Whitman, S., Good, G., Donoghue, E. R., Benbow, N., Shou, W., & Mou, S. (1997). Mortality in Chicago attributed to the July 1995 heat wave. American Journal of public health, 87(9), 1515-1518.

- Klinenberg, E. (2015). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

- Sinclair, U. (1906). The Jungle. Doubleday, Page & Co.