Blog by Claire Horn

In our accessibility series, Claire Horn reflects on the moral dilemmas presented by the advent of a new reproductive technology that allows for gestation outside the womb.

—Cristina Hanganu-Bresch

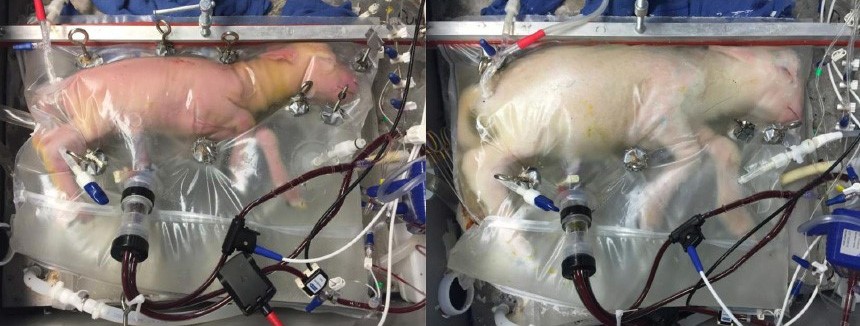

The last several years have seen significant progress toward the development of an artificial womb which would facilitate the survival and growth of prematurely born fetuses from approximately 23-24 weeks gestation onward. This is the current cusp of fetal “viability,” the point at which a fetus has a chance of survival outside of the womb, though morbidity and mortality for premature babies born before approximately 28 weeks gestation remains high. Artificial wombs, anticipated to be ready for human trials within the next five years, are innovative in that, rather than acting as a form of emergency life support for a neonate, they treat it as a fetus that has not yet been born. Surrounding the extremely premature baby in artificial amniotic fluid, they create an environment analogous to the uterus, allowing the fragile organs of the neonate to continue to develop as though it remained within the pregnant person’s body. If successful, this technology could significantly improve health outcomes for neonates and perhaps ultimately be engaged to support the health of pregnant people who encounter complications late in term.

Elsewhere, I have engaged a comparative approach to abortion law and drawn on feminist care ethics and reproductive justice scholarship and activism to contest a recurring claim in the literature on artificial wombs that this technology could or should mark the end of abortion rights.[1] But throughout this work, the question of access permeated my research: access to abortion without criminalization, access to safe, free, and appropriate reproductive care, access to the enabling conditions for reproductive choice to be more than lip-service to a discourse of liberal rights. The artificial womb, like many reproductive technologies before it, is likely to be expensive and limited to use in highly equipped neonatal intensive care units. Global disparities in health outcomes for pregnant people and neonates, as well as racialised disparities in these outcomes within the wealthiest nations stand only to be increased by the introduction of this technology. In the pursuit of technologies widely perceived to be fundamentally positive, such as interventions to sustain prematurely born babies, access is too frequently an afterthought. Technology is first produced, and questions are then posed about how it can be distributed equitably.

Elsewhere, I have engaged a comparative approach to abortion law and drawn on feminist care ethics and reproductive justice scholarship and activism to contest a recurring claim in the literature on artificial wombs that this technology could or should mark the end of abortion rights.[1] But throughout this work, the question of access permeated my research: access to abortion without criminalization, access to safe, free, and appropriate reproductive care, access to the enabling conditions for reproductive choice to be more than lip-service to a discourse of liberal rights. The artificial womb, like many reproductive technologies before it, is likely to be expensive and limited to use in highly equipped neonatal intensive care units. Global disparities in health outcomes for pregnant people and neonates, as well as racialised disparities in these outcomes within the wealthiest nations stand only to be increased by the introduction of this technology. In the pursuit of technologies widely perceived to be fundamentally positive, such as interventions to sustain prematurely born babies, access is too frequently an afterthought. Technology is first produced, and questions are then posed about how it can be distributed equitably.

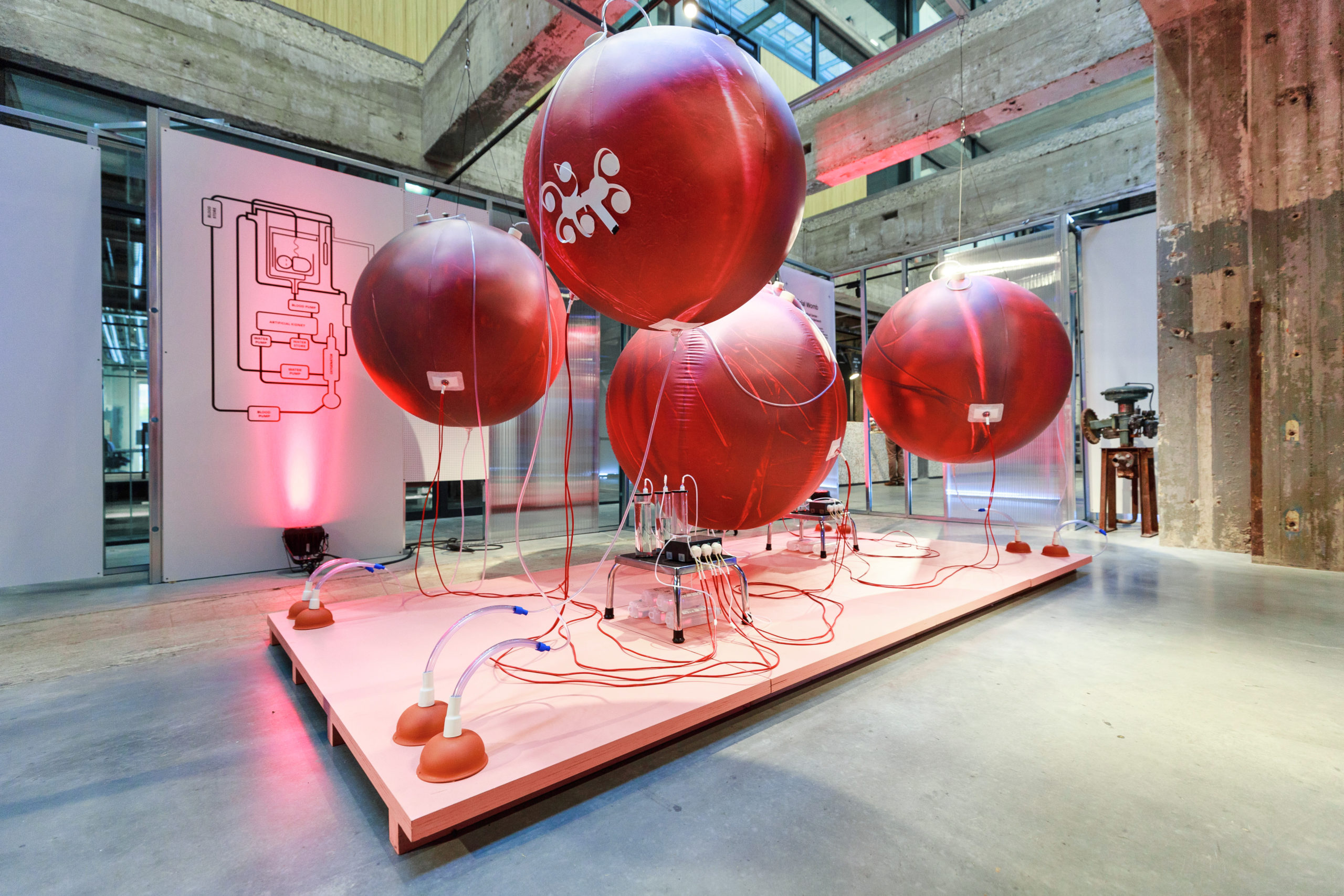

But in this period in which research toward an artificial womb prototype is ongoing, I argue that justice, accessibility, sustainability, and adaptability should be treated as fundamental to its development. These are concerns that begin at the level of design, with the question of precisely what materials and what systems will play a role in the technology’s use and function. How, for instance, might the social impact of the artificial womb change if it were constructed to be adaptable for non-expert use in multiple environments? This is at its heart a speculative question, but I argue that where we are imagining a technology still in its early stages, the process of such speculation, of considering the different forms that such an object might take, is vital to exploring issues of access and of care.

My new work takes as a departure point Murphy’s compelling invitation to consider that “the same bit of technology could—by being animated in different assemblages of technique, discourses, and subject positions—be meaningfully said to be two different things” (2012, 152). In one context, a costly artificial womb built for expert use in a neonatal intensive care unit, while deeply meaningful to those who are able to utilize it, can be said to be anathema to justice in closing stratified gaps in care. But in another context, in which each aspect of the technology’s design and implementation was informed by an imperative for access and adaptability, this technology might come to mean something very different. Experiences of reproductive care, from abortion to antenatal support to labour, are shaped by the environments in which they occur, and the extent to which a pregnant person feels safe, informed, and able to enact autonomy. Access is not solely about the cost and distribution of this resource, though these are vital considerations. It is also about in which settings, and by whom, an artificial womb might be used. How, for instance, would the meaning and experience of this technology change if it could be engaged by midwives, doulas, or pregnant people themselves?

There is a further point I am exploring, here too, pertaining to the relational experience of the artificial womb. The authors of the original biobag study cited the appearance of a baby in a bag as one possible design limitation, one which they have sought to address in part through features such as sound permeability allowing heartbeats to be played to the fetus within. But there is much more to be done here in understanding how (in)tangible elements of gestation might shape a relational encounter, and how these encounters might be altered depending on who (or what) is facilitating them. It is with these concerns in mind then, that I seek to speculatively explore the ways in which artificial wombs might be “animated” through questions of accessibility, adaptability, and justice. I would invite those whose work is preoccupied with designing, assessing, or legislating on such technologies to consider these questions as well.

Claire Horn is a Wellcome ISSF researcher at Birkbeck School of Law, where she recently submitted her PhD dissertation, “Gestation Beyond Mother/Machine: Frameworks for Artificial Wombs, Abortion, and Care.” Her research interests include ectogenesis, feminist legal theory, and reproductive technologies. Follow @clairemlhorn

[1] My previous (and forthcoming) work focused on comparing abortion regulation in Canada, the US, and the UK where the Abortion Act 1967 is in effect to demonstrate that artificial wombs could pose a challenge to abortion rights where these rights are regulated through criminal law and where viability is engaged as the point at which abortion is more heavily regulated. By contrast, in jurisdictions such as Canada (where abortion is decriminalized throughout pregnancy), the capacity of this technology to improve care for wanted preterm babies need not challenge abortion rights. Ahead of artificial wombs then, I argued for the necessity of decriminalization and improved access to all forms of reproductive care.