by Austin Lam

While ‘patient-centred care’ is an often used phrase, the question bears asking: what underlies such a broad concept?

As a medical student with a background in philosophy, I have endeavoured to integrate my journey in medicine with a philosophical sensibility. Part of that has led me to reflect on the meaning of the term patient-centred care.

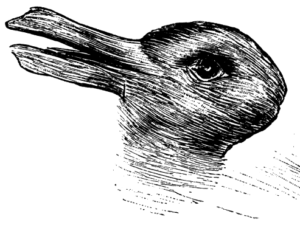

Professor Jennifer Gibson and Dr. Andreas Laupacis discussed patient-centred care as having several different meanings depending on one’s role in the health system. Patients, clinicians, hospitals, and organizations all bring their own points of view on the care experience. Notwithstanding the term’s variable meanings, philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer’s idea of a ‘Fusion of Horizons’ reveals an underlying thread, enriching our understanding of what we might more commonly refer to as perspective-taking.

‘Fusion of Horizons’ captures how our background, history, culture, education, language, and so forth enter into the conversations that we have with one another. Professor Fredrick Svenaeus elaborated on this Gadamerian concept and applied it to the practice of medicine in insightful terms: the patient-physician encounter is one that is fundamentally carried by their communication with one another – a dialogue.

A practice of perspective-taking (putting oneself in the patient’s shoes), as contextualized by a fusion of world views, is critical in shaping meaningful dialogue with the patient at the centre of the conversation. Professor Fredrik Svenaeus says:

The clinical encounter can be viewed as a coming-together of the two different attitudes and lifeworlds of doctor and patient – in the language of Gadamer, of their different horizons of understanding – aimed at establishing a mutual understanding, which can benefit the health of the ill party. Doctors are thus not first and foremost scientists who apply biological knowledge, but rather interpreters of health and illness. Biological explanations and therapies can only be applied within the dialogical meeting, guided by the clinical understanding attained in service of the patient and [their] health.

Vitally important to carrying out an effective perspective-taking approach is the recognition of the asymmetrical relationship between the patient and the physician. Professor Svenaeus rightly emphasized that: ‘The patient is ill and seeks help, whereas the doctor is at home – in control by virtue of [their] knowledge and experience of disease and illness. This asymmetry necessitates empathy on the part of the doctor. [They] must try to understand the patient, not exclusively from [their] own point of view, but through trying to put [oneself] in the patient’s situation.’

Gadamer’s ‘Fusion of Horizons’ enriches our understanding of what perspective-taking might look like because he viewed health as ‘a condition of ‘being there,’ of being in the world, of being together with other people, of being taken in by an active and rewarding engagement with the things that matter in life. … It is the rhythm of life.’

Thus, when perspective-taking, informed by a ‘Fusion of Horizons,’ forms the underlying architecture of a patient-physician encounter, physicians might be better equipped to:

- Reflect on how patients engage life in their own manner;

- Engage in a dialogue with patients where there is an understanding of the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and predicaments;

- Appreciate the patients’ interpretations of ‘the good life’ and the meaning of life.

Thinking back on my own experiences as a patient, I find that the notion of intersecting horizons becomes more vivid. I recall episodes of feeling unwell and wanting to know what was occurring and how I could feel better; I recall feeling anxious about my surgeries and seeking reassurance; and I recall the desire to tell my story to my doctor.

As patients (which we all have been, are, and/or will be), we give unprecedented access to our doctors not only to our physical bodies but also our minds and the ways in which we live our lives. The vast universes of our experiences are opened for examination. The doctor has the maps to navigate these universes which we each embody.

Notably, the patient, as the ‘liver’, the person who lives this universe, invites the doctor to guide them through the mysteries of their own universe. Here, the doctor brings in their own universe of experiences, including medical knowledge and know-how as well as their own life history. An intersection of horizons, then, entails a co-navigation process: the doctor is ‘at home’ in their knowledge, but they are working within the patient’s universe of experiences.

Drawing on my philosophy background, I have found it to be an illuminating experience to reflect on the meaning of patient-centred care and the conceptual foundation that allows it to ‘come to life’ in patient-physician encounters.

References

Svenaeus, F. (2003). Hermeneutics of medicine in the wake of Gadamer: The issue of phronesis. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 24(5), 407-431.

Acknowledgment: I am grateful for the support of Ms. Michelle Tremblay, formerly with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario as Senior Outreach Coordinator, who provided feedback and comments in the drafting process of this piece.