This guest blog post comes from Emma Barnard, a London based visual artist specialising in lens-based media and interdisciplinary practice and research within Fine Art and Medicine. Her solo retrospective exhibition Primum Non Nocere, focuses on the patient experience. The show has its private viewing on the 15th September 18.00-21.00, and then runs from the 16th September to the 7th October at Berlin’s Blue Art Gallery.

‘Without your medical file you don’t exist within this environment’. I will never forget those words, spoken to me by an ENT Consultant at what was the beginning of several years research as an artist into patient experience. This led me to the writings of French philosopher Michel Foucault and his book The Birth of the Clinic. It is said that Foucault coined the term ‘medical gaze’ to denote the dehumanizing medical separation of the patient’s body from the patient’s person or identity. Already at one of the most vulnerable times in their life, the patient can sometimes be viewed by their consultant as their diagnosis rather than as a person.

We’ve all heard the stories. As a further education lecturer, I remember after a particular class in which I happened to mention that my work as an artist involved coming into contact with patients, some of whom had been given a cancer diagnosis, a learner approached me and told me that he was diagnosed with cancer several years ago. The diagnosis, he said, was delivered so badly that he was left without hope. On his return home he gathered his family together and prepared them for the worst. When he attended subsequent treatment he was advised that they were hopeful of a recovery. He looked haunted when he told me his story, tormented for years by the delivery of that diagnosis. Another time, a healthcare professional told me that after her diagnosis she walked outside, fell back against the wall, and collapsed sobbing as a result of what she’d just heard. At that point, I was horrified to hear, she told me that she thought that she would rather die than go through with the advised treatment.

I felt led to do my small part as an artist in offering patients a voice. After observing the consultation I invite the patient into another consulting room and discuss how it feels to be them: right here, right now. I’ve now spoken to hundreds of patients from various departments. Every single person has answered that question differently, often surprising the consultant when they are shown the patients’ drawing afterwards. During the consultation process patients’ show little emotion; it’s quite difficult to read how they really feel about the impact of the words spoken during the clinical encounter.

So many different patient stories flood my mind as I write this. The reality of cancer was brought home to me fairly early on as I witnessed a patient who was without their larynx and therefore communicated through writing to ask the doctor how long he had to live, he needed to get ‘his house in order’. It was difficult for me to remain unmoved as I sat and watched this scenario play out in front of his wife and grandchild. I still have that writing as a powerful testament. In our current climate, with the richness of many different languages being spoken and the issues that this situation may pose when there is no one to translate, how much more difficult must it be when a person is unable to use the ‘voice’ that they are born with?

Patients facing life-threatening illnesses are heroic; they have allowed me to witness the brutality of a treatment that is intended to cure them, from surgery, through to radiotherapy, chemotherapy and subsequent complications that may arise from being the recipient of these. I am constantly humbled by their generosity in allowing me an insight into their world, but also their sheer courage when faced with a diagnosis that rocks their very existence.

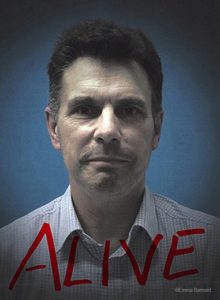

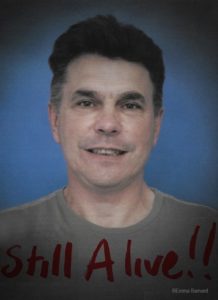

Out of hundreds of images I choose to show Martin’s. I know he will not mind me mentioning his name as, like many others, he is supportive of the work and keen for its exposure to a bigger audience. His writing cuts to the heart of what many cancer patients face when presented with their diagnosis.

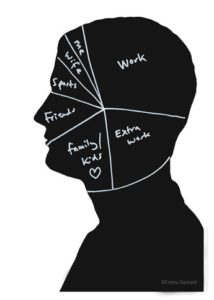

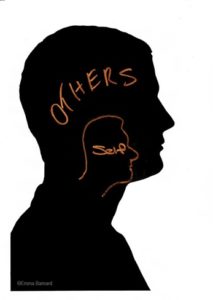

This work has now grown to encompass the surgeon’s view, the patient pathway, the surgeon/patient dynamic, and to include the experience of being a doctor in a busy outpatient clinic. The following images contain snapshots of the doctors’ experience in clinic between patients.

As an artist working collaboratively with doctors I feel privileged to have been given a fascinating insight into the field of medicine and I have a huge amount of respect for them, the work that they do and the immense pressure that they are under. They have incredible workloads, are overbooked in clinic, coping with funding cuts whilst often dealing with potential projections from patients of being ‘miracle workers’ and ‘life-savers’. I’ve seen the exhaustion, the despair, heard about the strikes, and know that currently many doctors are leaving the NHS to go abroad – consequently, there are not enough doctors to cover the workload. In their 2002 presidential address, neurosurgeons Stan and Raina Pelofsky write:

Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre suggested that alienation occurs when we divide the world into two distinct parts: the ‘true’ world of science is on one side, and the ‘flawed’ world of human perception is on the other. It’s as if we try to strip ourselves of human values in order to understand this perfect scientific world, and we begin to substitute science for meaning. But science alone is empty, and it threatens to separate us from our human connections…we neurosurgeons may become separated from our patients through our use of new technologies, by the hassles of our professional lives, or by lack of time. This in turn makes us isolated.

We might think to ourselves: We are the doctors – they are the patients. They are sick – we are healthy. We are objective and scientific; they are objective and emotional. This is a form of alienation and we have to understand it if we are to find ways to soothe it and become connected to our patients and to the essence of medicine.

This solo exhibition will allow me an incredible opportunity to showcase the perspectives that I have witnessed over several years as an artist working within medicine. I am selecting from hundreds of never-before-published images taken over the years. Primum Non Nocere will provide an insight into patient experience and the surgeon and patient dynamic, and it will expound on the air of mystery surrounding the surgeon’s practice, the immense pressure that they are under, and the harm that this may cause them.

Private view: 15th Sept 18.00 – 21.00

Exhibition dates: 16th Sept – 7th Oct