I was recently involved in a project which explored the histories and memories of St. Davnet’s Hospital, Monaghan. St. Davnet’s was founded as the Cavan and Monaghan District Lunatic Asylum in 1869, and its name changed to ‘Monaghan Mental Hospital’ in the late 1920s, and later to ‘St. Davnet’s Hospital’ in the 1950s. I was involved in this project through my engagement with Stair: an Irish Public History Company Ltd. This was a company which I co-founded with colleagues from the UCD School of History and Archives, with the support of Nova UCD. We saw the project advertised on etenders.gov.ie and put a bid together. The final project involved a number of strands, including an archives scoping exercise, the production of a book on the history of the site based on the archives, an oral history project, a community engagement project and primary schools programme, and the development of an exhibition on the history of the site at Monaghan County Museum. We were extremely lucky to have Monaghan County Museum as partners on this project, as they shared essential expertise, as well as part of their collection for the exhibition. Preparing an exhibition on the subject of mental health and mental illness, and on the history of one particular institution within the local town was not without challenges and difficulties. I wanted to write about the decisions that we made in selecting objects and stories for the exhibition, and in how we structured the overall narrative of the exhibition. Some further information on the project can be found here, in a site created by project manager and oral history lead researcher Fiona Byrne.

Nuts and bolts: We had a modest budget for the exhibition, which largely went towards the printing and production of panels for the exhibition, the creation of replica outfits and uniforms, and design and print of the catalogue, and other display-related costs (such as the glass heads for displaying nursing caps, above). We were lucky to be able to use the display cases, space and lighting at the museum, which cut down costs considerably. Some of these costs were also shared with the museum, which will be hosting the exhibition for a year. Installation and conservation of some objects brought from the hospital campus were taken care of by museum staff. As objects in the exhibition came from the hospital campus, from the museum collection and from private family donations, we needed to carefully document the provenance to avoid confusion at the end of the process.

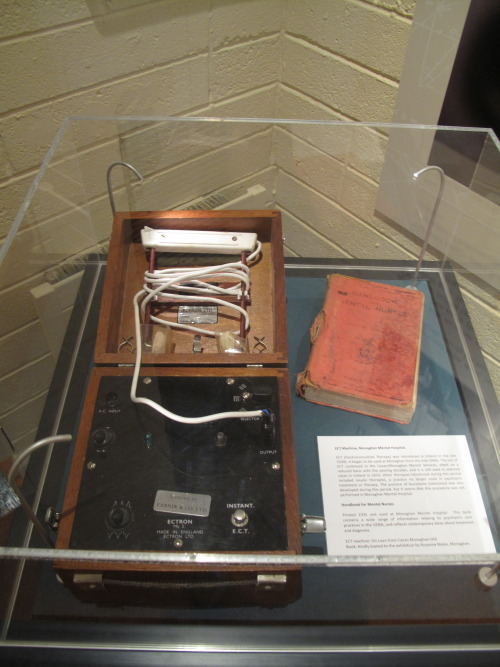

Putting the collection together: As with many exhibitions, the final selection of objects reflect a series of compromises between what we wanted to include, what we had access to, what we felt was appropriate to include, and what we could physically deal with in the exhibition space. Interestingly, our own process of creating the exhibition reflects that described by several of the contributors to the volume of essays Exhibiting Madness in the Museum: Remembering Psychiatry, edited by Catharine Colebourne and Dolly McKinnon. As in many of the cases outlined by Colebourne and McKinnon, we found that the history project commissioned by the HSE was precipitated by institutional change, with the hospital closing for admissions in 2012. The large site is now mostly used for administrative and community care purposes, with some long-stay patients still living in one ward. The ‘collection’ of the hospital was largely put together and defined in the process of creating the exhibition – again reflecting several of the examples mentioned by Colebourne and McKinnon. Throughout the process of talking with former and current members of staff, certain objects and spaces were marked as significant and important carriers of memory, and were included in the site. These included, for example, the Monaghan Mental Hospital fire helmet, the brown straitjacket and the large wooden table in the laundry building. Other objects were selected as part of our own investigation into the site, for example, drama trophies that had been presented to the St. Davnet’s Players and the Belfast sinks from the laundry. Some objects, such as the staff ration box from the early twentieth century, or nursing certificates and medals, were donated by former staff members living locally, who were extremely interested in the history of the site and who were very involved in the exhibition. Several items in the exhibition had already been collected by the museum – these included the chalice and paten from the asylum, an early wooden ECT machine, examples of modified knives and forks for patient safety, and a staff white coat from the 1960s.

The archiving process in place at the hospital also created something of its own collection – while this largely involves highly confidential hospital records, which will be archived, stored and managed by the National Archives, it also included architectural maps, plans and drawings, and a collection of personal effects, such as hair pins, pocket watches, rings, glasses and religious medals. These objects were removed from patients on entering the asylum or hospital – in many cases, they were returned, or returned to family members following the death of a patient. The personal effects that remain, therefore, are likely to have belonged to people who had been patients in the asylum or hospital, and who died there without relatives to claim their possessions. These items provide a very personal connection to the lives of those who experienced life within the walls of St. Davnet’s. The idea of personal effects has also been explored by artist Alan Counihan in his exhibition at the Grangegorman campus, another of Ireland’s large-scale Victorian asylum buildings. The use of personal items representing the transition between everyday life and the life of the asylum or hospital can also be seen in the exhibition ‘The lives they left behind: suitcases from a state hospital attic’, based on the suitcases of personal effects found at the former Willard Psychiatric Centre in New York State. Important items within the archive at St. Davnet’s also include the first admissions register and the first minute books of the asylum – the admissions register was included in the exhibition, but it was closed and locked to protect the privacy of those named.

The ‘World Within Walls’ project involved communication with members of the local community, former staff members, and former and current service users – reflected in the oral histories which were available via listening posts throughout the exhibition. An important part of the collection came from the items which had been kept by the families of former staff as important mementos of their time there. These will return to the owners at the end of the exhibition, but form an essential part of the overall collection represented in the museum. These items included very personal items, such a teapot given by a patient to a member of staff by patients and staff at the hospital on the occasion of her marriage, and a lace collar which had been given to the mother of the same staff member, made by a patient. Other items included official items, such as a key book which would have been held by the gatekeeper, recording each key being checked in and out, nursing exam slips, prizegiving booklets, photographs of sports teams and drama groups, nursing pins and certificates in both English and Irish. This brief description gives some sense of the variety of objects which were included in the exhibition collection, and the different processes by which they were collected.

Creating a narrative: One of the challenges in putting an exhibition like this together was to find a way to create a narrative which was both historically informed, and which presented information in a clear and valid way to visitors, without avoiding or over-emphasizing judgements on past practices in mental health care in Ireland. It is very clear that, from our contemporary position, many of the practices in mental health care were unacceptable, and many of those who were committed to institutional care could and should have been cared for at home. Indeed, many of those committed should never have been committed in the first place, while it is clear that others did need institutional care. The history of asylums and mental hospitals are inextricably linked to broader social histories of families, of sexuality and ideas of sexual morality in the country, and ideas about mental health and illness. We needed to find a way of presenting histories within their historical context, providing as much information as possible about the broad social context and contemporary ideas about mental health care in order to allow visitors to make up their own minds. This was absolutely essential as visitors to the exhibition, located in a local authority museum, would almost certainly include former staff members, former service users, current service users, and family members of both groups. Ideas of appropriate mental health care have changed radically, and we wanted to present information as accurately, sensitively and appropriately as possible. While certain groups – particularly former staff members – often had very positive memories of working on the site, where they formed strong friendships and often met their life partners, this had to be balanced with the (harder to source) memories of patients and service users, which were often more mixed, and could be negative. In presenting these differing views on such a recent, and profoundly local history, we wanted to make sure that each view was adequately represented equally, allowing people to explore them and to make up their own minds about the histories and memories being presented.

We were also mindful of the advice given by curator Nurin Veis in Colebourne and McKinnon’s book, mentioned above. According to Veis, ‘in presenting narratives of psychiatric history a curator must examine and determine whether one particular story is being emphasized at the expense of another. There is sometimes a tendency in museum displays to perpetuate the concept of past gruesome medical horrors in order to venerate the successes of modern psychiatric medicine’. We absolutely did not want to fall into the trap of emphasising the most negative aspects of the history of the site. It was overwhelming clear to us throughout the research process that a lot of genuine care existed within what could be a very harsh system. We found that there was sometimes an expectation that the very worst would be emphasised – that the history of this institution would be similar to the absolutely horrific institutional histories being uncovered with regard to the Mother and Baby Homes and the Magdalene Laundries, for example. While there were, undoubtedly, many examples of unjust and sometimes horrific treatment within institutions of mental care, these must be balanced with a representation of daily reality. At the end of the process, it felt to me that the greatest injustice was the boredom, monotony and loss of liberty and self-determination suffered by many patients, particularly up to the 1960s. We wanted to present this history fairly and honestly. In trying to understand these systems, it can be difficult for people to accept that there was no one driving force, no one figure or institution that can be vilified and perhaps punished, but rather a whole range of social forces that contributed to the situation. At some of the public events where we presented our ideas for the exhibition, we sometimes felt under pressure to fit this history into a larger story of institutional abuse in Ireland – whereas there are some points of connection, it is a very different history, and must be engaged with on its own terms. The local context for the exhibition was also in our minds in creating these narratives – together with the advice given by Veis, we were loath to perpetuate stereotypes about what happened ‘inside’, risking reinforcing stigma around mental illness and mental health care. The balance between providing accurate and accessible information about life within the asylum and the hospital without falling into potentially damaging stereotypes was certainly a challenge for the exhibition team (myself, Fiona and Liam Bradley, curator at Monaghan County Museum, supported by the staff there and the steering committee of overall project led by the HSE).

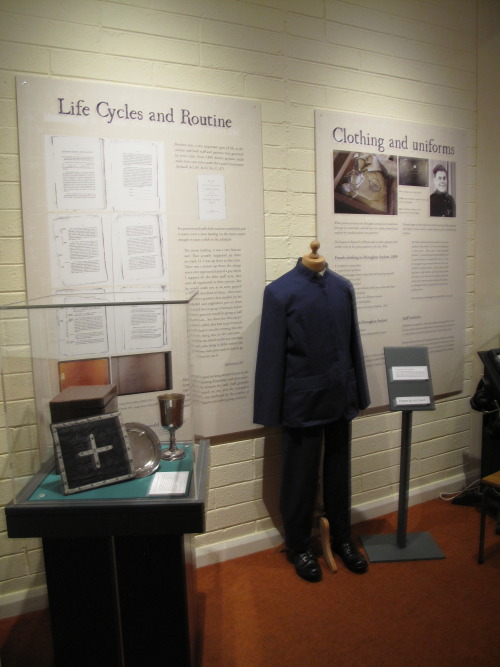

In the end, we decided to focus on the shared life experiences ‘within the wall’s of St. Davnet’s through a number of key themes, rather than trying to deal with patient and staff life separately. This emphasis on the lives and experiences of those who spent so much of their lives within the walls of the hospital was signalled by the first object encountered by visitors – a replica of a female patient uniform (made by a local dressmaker using early 20th century photographs as a guide, as no originals remain). This decision reflects the fact that patients, on first entering the asylum or hospital, would have had their clothing and personal belongings removed, been given a hot bath, and the serviceable but anonymous uniform of the hospital. The themes chosen were ‘Building St. Davnet’s’ (maps and plans, an overview of the site, a timeline with major events within the hospital, put in context by major national or world historical events, a video walk-through of the site which provided an overview of the buildings and campus as it exists, an interactive map which people could use to orient themselves around the campus, and an 18th century book of maps which showed the site in relation to Monaghan town before the asylum was constructed). If you are interested in this aspect of the history, you can read my essay from the book on the asylum and hospital architecture here. The next section focused on the ‘World of Work’, and explored the kinds of work carried out by both patients and staff on the hospital grounds. The objects chosen for this part of the exhibition included sinks, a large wooden table and a fabric brand used in the hospital laundry, a place where many female patients would have spent long hours working, a fire helmet from the hospital fire brigade, a whistle used in reporting escaped patients, as well as images of staff in uniform, reflecting changes throughout the years. Information from the archives on staff and patient work (including when patients started to get paid for their work) was on the panels – we did not include any photographs of identifiable patients or service users in order to protect anonymity, but aimed to represent their experiences as fully as possible from the archives. The oral histories were an important part of this section, reflecting memories of work on site in the farms and on the wards. We also included a section on the well-known ‘Soviet’ or strike at St. Davnet’s in 1919, led by Peadar O’Donnell, and a section on nursing, including information on training, exams and everyday patterns of life as a nurse on the wards.

The next section was based on ideas of illness and recovery, and included a bed from the hospital, an early ECT machine and handbook on nursing and mental illness, as well as key information on reasons for committal, types of treatments used (including highly controversial treatments such as insulin comas), and experiences of illness that crossed the boundary between staff and patient, such as the Spanish Flu and the TB epidemic in Ireland, when part of the new buildings were used as a TB hospital for a period of time. We used doors from the hospital as dividers between the exhibition sections – many of the visitors to the site itself during a Heritage Week tour in August 2014 remarked on the sense of repetition and monotony produced by the endless wards and doors throughout the vast complex of buildings – while we could not replicate this within the temporary exhibition space at the museum, we tried to give a sense of the internal environment by using these doors, and also through the video walk-through, the use of hospital screens from the campus, a commissioned soundscape which gave an idea of the aural environments on site, and a video of a sports day on campus from the 1930s (which doesn’t show any patient faces clearly), displayed at the back of the exhibition).

The final section was based on the idea of everyday life within the asylum and hospital. This, in some ways, was one of the most poignant aspects of the exhibition, reflecting the lives spent, often isolated and removed from the wider world, within the walls of the hospital. Oral histories which told of patients missing the moon landing on television as their routine meant that they had to go to bed – this is a microcosm of the world of routine and structure experienced by many, where they lacked self-determination and autonomy. A section on the development of mental health care policies included at the end of the exhibition, and prepared by the HSE, gave an overview of how new policies from the 1970s aim to change this, with a more patient-centred approach. Some of the objects from this section of the exhibition are listed above, but also included the removable taps from the baths (for patient safety), the keys allowing access to either the male or female wards, but not both (patients were segregated by gender to the latter years of the 20th century), the modified knives and forks used by patients, and also the chalice and paten from the asylum, marked as such, reflecting the role that religion played for patients – there is a Catholic and a Church of Ireland chapel on campus, as well as a graveyard, where some patients who died in the asylum or hospital were buried.

Finally, the last section of the exhibition included a panel on mental health and language, explaining the different terms used throughout the exhibition (including some terms that would be offensive today such as ‘lunatic’ and ‘imbecile’), and a panel on current mental health care directions provided by the HSE. The desk of the Resident Medical Superintendent was included here, and visitors could sit down, and write their own thoughts and reflections on the exhibition, to be hung on a clothes line with wooden pegs behind the desk. Further reading material on the history of the site was provided here, as well as information on mental health care services in the area, and contact numbers for people to use if they were impacted by any of the issues raised by the exhibition. We thought long and hard about including trigger warnings, but in the end, felt that the initial exhibition materials outside the room provided adequate information about its content, without sensationalising the subject matter. A final note – the exhibition was produced in association with the HSE, and therefore does reflect their views on current mental health care policies. We retained as much curatorial and scholarly freedom as possible throughout the presentation of historical material, and based this on best practice developed by curators and scholars on the subject internationally. There is a lot more that I could write about this subject, but I wanted to quickly put together a blog post before I forgot some of the discussions and debates that we had in putting it together. We would have been happier to have the strait jacket at the back of the space, rather than having it front and centre, but this was the only place that this exhibition cabinet could be placed due to the need to use the space for education workshops throughout the run of the exhibition, so some compromises had to be made. The exhibition will run until Feb 2016, and will then be available to tour to other venues.

For more information on the history of mental health in Ireland – Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland (CHOMI) at UCD, as well as the publication of several recent books and collections of essays on the subject of psychiatric history by scholars such as Catherine Cox, Lindsay Earner-Byrne, Brendan Kelly and Pauline Prior, adding to the work carried out by those such as Mark Finnane on mental illness in Ireland after the Famine, and Joseph Reynolds on Grangegorman asylum.

Correspondence:

Dr. Niamh NicGhabhann,University of Limerick

niamh.nicghabhann@ul.ie