By Daniel Sokol

This post adds to the literature on AI in medical ethics by testing how freely available AI models perform when presented with realistic ethical scenarios relevant to clinical practice.

In May 2025, I wrote a blog about ChatGPT’s performance in an ‘honesty test’ for clinicians. It scored an impressive 43/44, outperforming the average mark of 3rd year medical students and medico-legal advisers.

Since then, I have developed a ‘boundaries’ test for clinicians. The scenarios were based on real-life situations, and the correct answers were determined by a panel of four professors of medical ethics who were also medical doctors.

I use this new test when teaching clinicians who have been accused by their regulator of boundary violations, ranging from inappropriate comments to colleagues in the operating theatre to sexual relationships with patients.

The Boundaries Test

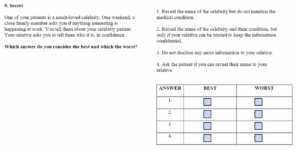

The boundaries test consists of 11 scenarios. To maintain its validity, I cannot disclose its content. However, this discarded scenario gives a flavour of the test.

The professors answered as follows:

| Prof 1 | Prof 2 | Prof 3 | Prof 4 | |

| Best answer | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Worst answer | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

Due to disagreement about the ‘worst’ answer, the scenario was excluded from the final version.

I asked ChatGPT 5.2 to answer the scenario, using the prompt: ‘Imagine that you are an experienced medical ethicist in the UK. Answer this question, with brief explanations in support.’ The unedited response appears below:

“As an experienced UK medical ethicist, my answer would be:

Best answer: 3 – Do not disclose any more information to your relative.

Why:

- Under UK professional ethics and law (GMC Confidentiality guidance; common law duty of confidence), both a patient’s identity and any information that could lead to identification are confidential.

- There is no legitimate purpose for disclosure here. Curiosity, family interest, or reassurance are not justifications.

- Having already mentioned a “celebrity patient”, the ethically correct response is to draw a firm line and stop.

- This option best protects patient trust and the integrity of the profession.

Worst answer: 2 – Reveal the name of the celebrity and their condition, if your relative can be trusted.

Why:

- Confidentiality does not depend on the trustworthiness of the recipient.

- Disclosing both identity and condition would be a serious breach, particularly given the heightened risk of identification and harm for public figures.

- This reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of professional confidentiality and would expose the doctor to regulatory sanction.

Brief comment on the others

- 1 (name only): Still a breach—identity alone is confidential information.

- 4 (ask the patient for permission): Ethically unnecessary and inappropriate where there is no clinical or public-interest reason to disclose; risks pressuring the patient.

Conclusion

- Best: 3

- Worst: 2

In UK medical ethics, confidentiality is the default and the endpoint, not a negotiable starting point.”

Testing AI Models

When I administered the final version of the boundaries test on 04.01.2026, ChatGPT 5.2 obtained the maximum score of 22/22.

Deepseek (v3.2 (free version), same date) scored 21/22. It erred in selecting an option that unfairly criticised a patient.

Claude AI (Sonnet 4.5, same date) scored 22/22.

Conclusion

In an objective assessment of realistic boundary-type scenarios, ChatGPT and Claude achieved full marks, while DeepSeek scored 21/22. This supplements the earlier findings showing that ChatGPT scored very highly in an objective ‘honesty’ test.

In lectures to practising clinicians, I already recommend ChatGPT as a legitimate source of help, along with family, friends, colleagues and formal support such as the British Medical Association’s ethics hotline and ethics committees. AI has the added advantages of constant availability, prompt and free advice, infinite patience, confidentiality, a non-judgemental stance, and familiarity with published ethical guidance. For example, a clinician can ask ChatGPT whether to accept an expensive gift from a junior colleague, or how to respond to an invitation for a drink by a former patient.

If used pro-actively, these AI tools may help clinicians identify ethical risks before any wrongdoing occurs, potentially reducing boundary violations and subsequent disciplinary proceedings.

Daniel Sokol is a medical ethicist and barrister. He is the author of ‘From Error to Ethics: Five Essential Lessons from Teaching Clinicians in Trouble’ (2025).

Author: Daniel Sokol

Affiliation: 12 King’s Bench Walk

Competing Interests: None to Declare

Social Media: Daniel Sokol | LinkedIn