By Rafael Escandon

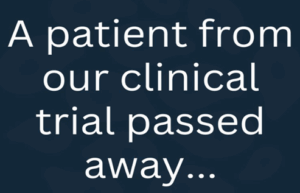

A recent social media posting got my attention for a couple of reasons. First, because it is quite unusual and second, because the detail behind the headline tells a different story than the headline suggests.

This was the first posting since the advent of social media where I have seen a company or their representative report a trial participant’s death in such a way. Contrasting this headline with the additional details behind it inspired an examination of what, if anything, our common morality says about permissible ways to attract attention to and to report consequential things such as deaths, harm and cutting-edge developments in science, medicine and clinical research.

From the perspective of a clinical trialist and ethicist, read in isolation, the headline indicates that the worst thing that can happen in one’s clinical trial did, i.e., a trial participant died while on-study. That conclusion would be a mistake however, as the further detail clarifies that the participant died from a cause other than their serious and refractory primary disease after having received an investigational intervention in a trial sponsored by the poster’s company. The post does not include a notation of adverse events or risks and trade-offs but also reports similarly positive responses for another five recipients with similar prognoses. Thus, potentially transformative news for a group of patients with limited reasons for hope was reported behind a headline that, viewed in isolation, led at least one clinical trialist/ethicist to a much more disquieting conclusion.

My broad concerns with this post are four; 1) that appropriate consent was obtained from the participant or their survivors to report their death in such a fashion, 2) because this was a current or previous trial participant – was adequate privacy, dignity and respect for them maintained, 3) that all claims within the post are objectively verifiable and 4) was the intent of the headline pure in its intention to honor the research participant, or was it (even unintentionally) used to draw attention to something else?

To examine this case, a clinical researcher might likely reference elements of the Declaration of Helsinki or Kraft and colleagues’ work that make clear the research team’s responsibility to respect and maintain participants’ dignity and, therefore, the public’s trust. These principles are also embedded in the more “how-to” standards of Good Clinical Practice. A bioethicist might be most apt to reference the positions of Immanuel Kant, and his stated duties of truthfulness and imperative for not using a man as a mere means to one’s desired end, in both research and of its reporting.

But what proportion of the population has studied Kant or finds his positions relevant? And what proportion of business leaders are familiar enough with the Declaration of Helsinki and with GCP principles to have either impact company communications on social media? The post’s nearly 60 written comments (and over 1,100 positive reactions) are broadly congratulatory, with only two comments expressing concern or disapproval at the time of this writing. Considering the reactions, it seems reasonable to conclude that those who engaged largely looked beyond the headline and focused on the positive, though anecdotal, message. What is less clear is whether the reactions are a tacit endorsement of this style of communication for anyone reporting clinical research results.

Assigning weight to anecdotes unchecked by clinical/scientific experts with no peer-reviewed publication(s) referenced is also hazardous. In the early stages of clinical development, language has traditionally been highly transparent and cautious for good reasons. Highest among those reasons is respecting participants and their decision to volunteer. Presenting clear, objective, peer-reviewed and unbiased data through a trusted expert practitioner and research team prepared to answer questions is a fundamental way to respect autonomy and to responsibly solicit volunteerism.

The transformation in the ease and speed of collection and integration of trial data that digital tools have introduced is remarkable – ideally making emerging data on efficacy and harm available to stakeholders in near real-time. However, it is the assessments of the data quality, its analysis, and application of wisdom by clinical experts that adds time to the process – time which enables a greater understanding of risks, benefits and outcomes to be communicated to participants in the consent process. A question for society is whether we believe that the speed and limited context of social media posts can meet these information quality, completeness, and context bars that current and prospective research participants deserve.

We’re now in a zone of experience that occasionally diverges from the days in the not-too-distant past when, for example, cytotoxic chemotherapies demonstrated incremental improvements in progression or survival with numerous tradeoffs in quality of life. Complete and transparent presentation is essential in avoiding giving those with severe, refractory or orphan conditions false or over-indexed hope. The stakes are especially high now because health misinformation from social media can introduce significant tension into every aspect of the trust-bound relationships between participants and the research team.

Nonetheless, the occurrence of real and transformative outcomes is beginning to test the traditional framework for presentation of trials to potential participants. Now, some patients with genetic and hematologic malignancies may have the possibility of transformative effects, even in First in Human (FIH) studies. Increasing possibilities for remission have major implications to the informed consent process, and must be examined by disease, standard of care, investigational agent and each participant’s risk tolerance and support system.

This case, and another, summarized in a recent article about the ramifications of stillbirth to those involved in surrogacy emphasize the same challenges. Can or should evolution of our societal norms, standards for bioethics and reporting of information match the rapid pace of innovation seen in virtually all areas of medical science? Failure to engage in discussions about ethics and best practices risks turning human subject research and adoption of new treatment practices into “transactions” bound more by purely legal contracts than by the valued human components and quality standards of today. If we do not engage, those human elements may be irretrievably forgotten.

Author: Rafael Escandon, DrPH, PhD, MPH, HEC-C

Affiliation: DGBI Clinical Research and Ethics Consulting, Bainbridge Island, WA, USA

Competing Interests: None declared