By Daniel Sokol

In February 2023, I wrote on this forum about a new honesty test for doctors.[1] Developed with an experienced clinical psychologist, the test was a Situational Judgement Test of 22 real-life scenarios involving truth-telling problems. The ‘correct’ answers were determined by six professors of medical ethics who were also medical doctors.

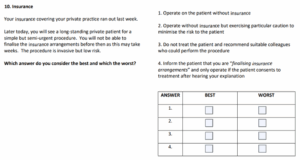

To give a flavour of the test, I included an example of a scenario which was ultimately discarded from the final version:

The best answer, according to the panel of learned professors, is 3 and the worst is 1.

As there are two answers per scenario, the maximum score in the honesty test is 44.

Previous testing

In July 2023, I administered the test to 19 medico-legal advisers and paralegals at a medical defence organisation. The median score was 40 and the mean was 39.4.

In November 2023, 139 4th year medical students at the University of Birmingham took the test under supervision. The median score was 41 and the mean 39.8.

Since then, hundreds of clinicians on my remedial ethics course have taken the test. Most score between 39 and 42.

Testing ChatGPT

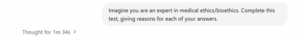

On 22nd May 2025, I asked ChatGPT, version o3, to complete the test, using the prompt below:

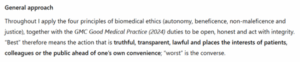

ChatGPT is a principlist, with a twist

The first surprise was that ChatGPT purportedly used Beauchamp and Childress’ four principles of medical ethics. It made the common error of calling one of the principles ‘autonomy’ rather than ‘respect for autonomy’.

ChatGPT appeared to supplement a principlist analysis by reference to other values such as integrity, professionalism and prudence.

The score

The second surprise was its test result: 43/44. This exceeds the vast majority of medical students, medico-legal advisers and clinicians who have taken the test to date.

In its reasoning, ChatGPT referenced:

- Ethical notions, such as integrity, truthfulness and consent

- Legal concepts, such as theft, fraud and duty of candour

- Regulatory guidance of the General Medical Council

- Expectations set by COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics)

- Guidelines from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)

The error

ChatGPT’s sole error resulted from a failure to recognise the mandatory nature of a requirement.

When I pointed this out to ChatGPT, it responded ‘Thank you for pushing on the nuance here’ and reached the right answer.

An example of ChatGPT’s ethical reasoning

To preserve the validity of the honesty test, I am unable to disclose its scenarios or ChatGPT’s comments on them. However, I have asked ChatGPT to answer the insurance scenario above, using the same prompt as before. The full response, which appears below, sheds light on ChatGPT’s methodical approach to such ethical problems.

‘Best answer → Option 3: “Do not treat the patient and recommend suitable colleagues who could perform the procedure.”

| Why this is the most ethical course | Key principles it satisfies |

| Meets statutory & professional duties. The General Medical Council (GMC) requires every doctor who practises in the UK to have “adequate and appropriate insurance or indemnity” in place at all times; practising without it can trigger fitness-to-practise action and loss of licence. (GMC UK, The MDU, BMJ) | Professional integrity, Justice |

| Protects the patient’s right to compensation. If something goes wrong, the patient retains a clear route to redress because the colleague you refer to will (or should) be properly indemnified. | Non-maleficence, Justice |

| Maintains timely care. A prompt referral honours the patient’s clinically semi-urgent need while avoiding unlawful practice on your part. | Beneficence |

| Is transparent and honest. You openly acknowledge your current limitation and arrange an alternative rather than obscure or down-play it. | Autonomy (truth-telling) |

Worst answer → Option 1: “Operate on the patient without insurance.”

| Why this is the poorest course | Key principles it breaches |

| Contravenes GMC rules & the law. Performing private work with no indemnity flagrantly violates GMC Good Medical Practice and statutory obligations. (GMC UK, The MDU) | Professional integrity |

| Leaves the patient unprotected. The patient would have no guaranteed means of compensation if an adverse event occurred. | Non-maleficence, Justice |

| Provides no disclosure or consent about the risk. The patient’s autonomy is ignored because you conceal a material fact. | Autonomy |

| Exposes you to personal liability and reputational harm. In addition to ethical failings, you risk personal financial ruin and GMC sanctions. (BMJ) | Prudence (self-care), Professional integrity |

Brief comments on the remaining options

- Option 2 – Operate without insurance but “exercise particular caution.”

Trying to be extra-careful does not cure the core problem: the act remains professionally unlawful and leaves the patient uncompensated. Ethically it is marginally better than Option 1 because at least you show concern for safety, but it is still unacceptable. - Option 4 – Tell the patient you are “finalising insurance arrangements” and proceed if they consent.

Transparency is an improvement, yet the practice is still prohibited; a patient cannot waive your statutory duty to hold indemnity, and the wording risks misleading them into thinking cover is imminent or already partly in force.

Hence, Option 3 is the only answer that simultaneously respects the patient’s welfare and autonomy and keeps you within professional and legal boundaries, while Option 1 is the clearest violation of both.’

Conclusion

ChatGPT, version o3, performed impressively – though not perfectly – in a situational judgement test focussed on medical ethics. Its answers aligned closely with those of experienced medical ethicists and its reasons were generally sound.

It outperformed most 4th year medical students and doctors on my remedial ethics course, as well as a small group of medico-legal advisers.

Doctors facing ethical problems should seek advice from friends, colleagues, ethicists or an ethics committee. However, ChatGPT is now a credible ethics adviser, with the added advantages of constant availability and infinite patience. Doctors with a smartphone and internet connection can have their own, on-call medical ethicist at hand.

ChatGPT is nonetheless fallible and, for important matters, a second opinion from an old-fashioned human is advisable.

Daniel Sokol is a medical ethicist and barrister. He is the author of ‘From Error to Ethics: Five Essential Lessons from Teaching Clinicians in Trouble’ (2025).[2]

Author: Daniel Sokol

Affiliation: 12 King’s Bench Walk

Competing Interests: None to Declare

Social Media: X: DanielSokol9

[1] https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2023/02/14/developing-an-honesty-test-for-doctors/

[2] https://shorturl.at/HdGID