By Helen Lynne Turnham, Sarah-Jane Bowen, Sitara Ramdas, Andrew Smith, Dominic Wilkinson, Emily Harrop.

Children with medical complexity and technology dependence are at constant risk of sudden death or catastrophic complication. In some cases, their diagnoses may mean that their lives are likely to be short regardless of treatments offered, and remaining in hospital, particularly in an intensive care unit, may greatly limit their quality of life.

Some of these children will never reach the conventional levels of stability described in guidelines for community care. The choices available to them are a life of limited quality, away from home and normal family life, or a tolerance of higher than usual risk of morbidity or mortality.

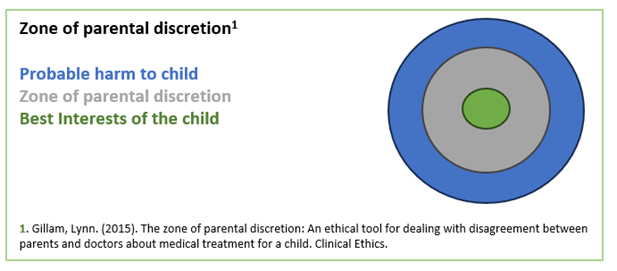

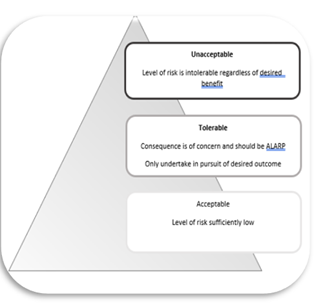

In our paper ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP), a Moral Model for clinical risk management in the setting of technology dependence’ we discuss the ethics of decision making for these children, for whom there is no obviously ‘good’ option. We use the concept of the Zone of Parental Discretion to examine the navigable space between best interests and significant harm.

Working with a safety expert from the airline industry, we have used the ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) model to examine risk, which cannot be fully mitigated.

Dr Helen Turnham, consultant paediatric intensivist with Dr Sara-Jane Bowen, consultant in paediatric respiratory medicine shared : ‘Working with children and families to make difficult decisions for children who cannot make decisions for themselves is often challenging, but more so when there are no good options and only difficult choices open to the child. Chloe has been extremely generous in allowing us to share Gracie’s story, to share the challenges and pain of children and their families living with difficult decisions. As clinicians responsible for supporting high risk choices for children, we live with moral distress and understandable moral fear of potential consequences. Meeting with Chloe, so many years after Gracie died, sharing her belief that they ‘would fight to do the same again’ highlighted the importance deliberating on this moral problem and developing a moral framework to support families and clinicians making difficult decisions when children and their families face similar circumstances as Gracie and Chloe.

Andrew Smith, air safety expert reflected that ‘assessing risk for children with complex medical problems is far more challenging than for aircraft and aviation systems. Each assessment must be completed individually, balancing the potential positive and negative outcomes for the child and their families. The concept of ALARP allows skilled medical staff to work with families to document the risks within a consistent framework. It allows staff, patients and families to accept some level of risk in order to also accept an improved quality of life for patients where a traditional risk assessment approach might lead to a risk-adverse rather than a risk-aware decision. Applied diligently, I believe the ALARP concept can bring access to improved quality of family life for some children whilst mitigating the risks as much as possible within the constraints of what is possible outside of a clinical setting’.

Dr Sithara Ramdas, Consultant Paediatric Neurologist said: ‘As a neurologist, many of my patients have life limiting conditions. However, most do for several years have excellent quality of life, enjoying normal day to day activities with loved ones despite their complex neurological problems. But sadly when the underlying disorder progresses to an extent that medical interventions may sustain life but limit the ability of child to have any quality of life, ALARP provides a framework for families and professionals to acknowledge that there will be level of risk involved in the decisions made to prioritise quality of life over sustaining life at all costs and this risk is entirely acceptable.’

Dr Emily Harrop, consultant in paediatric palliative care, stated ; ‘I see the value of a child with a life limiting illness being able to leave hospital very clearly within my patient population. Some children will not have left an intensive care unit for months, and may have had very little access to normal family life. Just being outdoors, or seeing a much loved pet can make all the difference. If the alternative is a slightly longer life, with no opportunity for discharge, the options should be discussed openly with families and with the multidisciplinary team involved. ‘

Prof Dominic Wilkinson concluded: ‘One of the features of a true ethical dilemma is that there are no obvious right answers. In fact, as in the cases we discuss, sometimes the only choices available all involve significant ethical costs, indeed they all appear to be harmful to the child in one way or another. In a situation where all options involve harm, we argue that clinicians should aim for the least worst option – aiming to ensure that risks are as low as it is reasonably possible to make them. Such choices are inevitably uncomfortable, but we hope that this model and paper helps clinicians navigate these difficult decisions and reach the right decisions for this group of vulnerable children.

Authors and affiliations:

Helen Lynne Turnham: Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

Sarah-Jane Bowen: Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

Sitara Ramdas: Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

Andrew Smith: Royal Aeronautical Society, London, UK

Dominic Wilkinson: Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK; Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Emily Harrop: Helen and Douglas House, Oxford, UK

Competing interests: None declared