By Tara Hurst, Tess Johnson, Euzebiusz Jamrozik, Phaikyeong Cheah and Michael Parker.

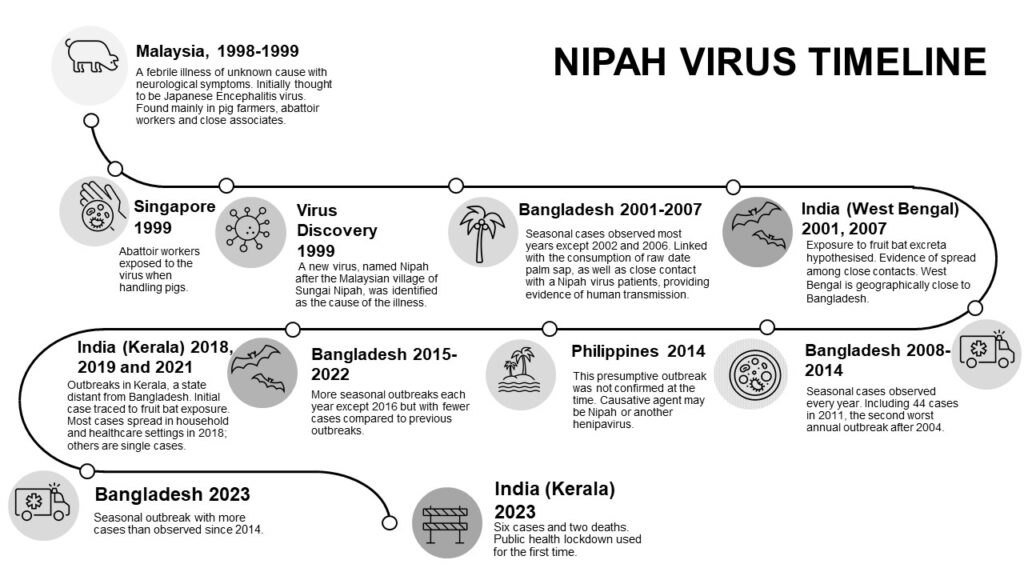

Nipah virus made the international news recently for an outbreak in Kerala, India. This bat-borne virus has occurred seasonally in Bangladesh since the first outbreaks were identified in Malaysia and Singapore in 1998-1999 (Figure 1). The course of Nipah virus disease may be mild or severe; patients present with fever, headache and respiratory symptoms and may develop encephalitis, which can lead to seizures, coma and death. The virus is notable for its very high case fatality rate, causing death in 40-75% of cases. What with this and an absence of medical countermeasures, Nipah virus has earned a place on the World Health Organization’s priority pathogen list (Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts (who.int)).

In the latest Kerala outbreak, there were six cases and two deaths, giving a case fatality rate (CFR) of 33% (Figure 1), lower than many past outbreaks. The Kerala Minister for Health, Veena George, attributed this to excellent medical treatment and monitoring efforts against the outbreak. These efforts included a regional lockdown, school closures, mask mandates, contract-tracing, and travel restrictions. Since the outbreak was contained, these measures could deemed successful.

However, the public health response to the outbreak is open to ethical scrutiny and debate, as are other aspects of public health measures and research efforts against Nipah virus disease. Despite the ground being ripe for ethical discussion, there is almost none in the academic literature. In our article (Ethical issues in Nipah virus control and research: addressing a neglected disease), we highlight why ethical work is needed on this topic. For instance, we ask whether the outbreak response in Kerala was consistent with the transmission dynamics of the disease, which passes from person to person via close contact. Where transmission is limited in this way, measures like contact-tracing and isolation of infected individuals can be particularly effective, but other measures like lockdowns may provide little to no benefit to the population. This begs the question of whether it is ethical to enforce such restrictions.

There are multiple risk factors for increasing the spread of zoonotic viruses to human populations and these are related to human activities characteristic of the Anthropocene: altered and increased land use for agriculture and urbanisation, as well as climate change. With these environmental pressures intensifying, the risk of outbreaks of known and novel zoonotic pathogens, including Nipah virus, is increasing. Global attention is finally turning towards Nipah virus, including the development of vaccines and the design of non-pharmaceutical measures that could help manage exposure to Nipah virus.

Widely varied measures are up for consideration and debate. The first outbreak was curtailed by mass culling of infected pigs, which were the intermediate species that then transmitted the virus to workers in the pork sector. The presumptive reservoir host, fruit bats, have a wide geographical spread and so culling them is not possible; it is also likely that other species may carry and transmit the virus, so targeting bats alone is unlikely to work even if it was ethical (Nipah outbreak: ‘Driving away bats is not the answer’ – Frontline).

Others suggest monitoring bats as a way to be prepared for a new outbreak (Monitoring fruit bat colonies could provide early warning for Nipah outbreaks (nature.com)). This is indicative of a One Health approach, which involves approaching outbreaks of pathogens in the context of the wider ecosystem and animal populations. Indeed, a One Health centre has just opened in the Government Medical College in Kozhikode, the district of Kerala affected by the Nipah outbreaks in 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2023 (Kerala One Health Centre for Nipah Research opened). The debate on how best to manage such outbreaks opens the door for world-leading clinical, epidemiological, and policy work on Nipah virus, and ought to be supported by embedded ethical work.

Our paper (Ethical issues in Nipah virus control and research: addressing a neglected disease) explores the ethical issues particular to Nipah virus disease. Largely, these issues emerge from reflection on how the virus impacts the affected communities, including the disease itself and potential related effects such as stigmatisation, surveillance, or threats to communities’ traditional food practices. We also outline the ethical questions raised by research into vaccines, therapies, and non-pharmaceutical measures to limit exposure or transmission. There is not a body of ethical work to draw on for Nipah virus – yet. It is our hope in writing the article that this will encourage an ethical appraisal of Nipah virus disease.

Paper title: Ethical issues in Nipah virus control and research: addressing a neglected disease

Author: Tess Johnson1,2, Euzebiusz Jamrozik1,2,3, Tara Hurst2, Phaikyeong Cheah1,4,5, Michael Parker1

Affiliations:

1 Ethox Centre, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

2 Pandemic Sciences Institute, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

3 Royal Melbourne Hospital Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

4 Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

5 Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Competing interests: None declared.

Social media accounts of post author:

@drtessjohnson @ID_ethics @phaikyeong @michaelethox