By Charlotte Duffee.

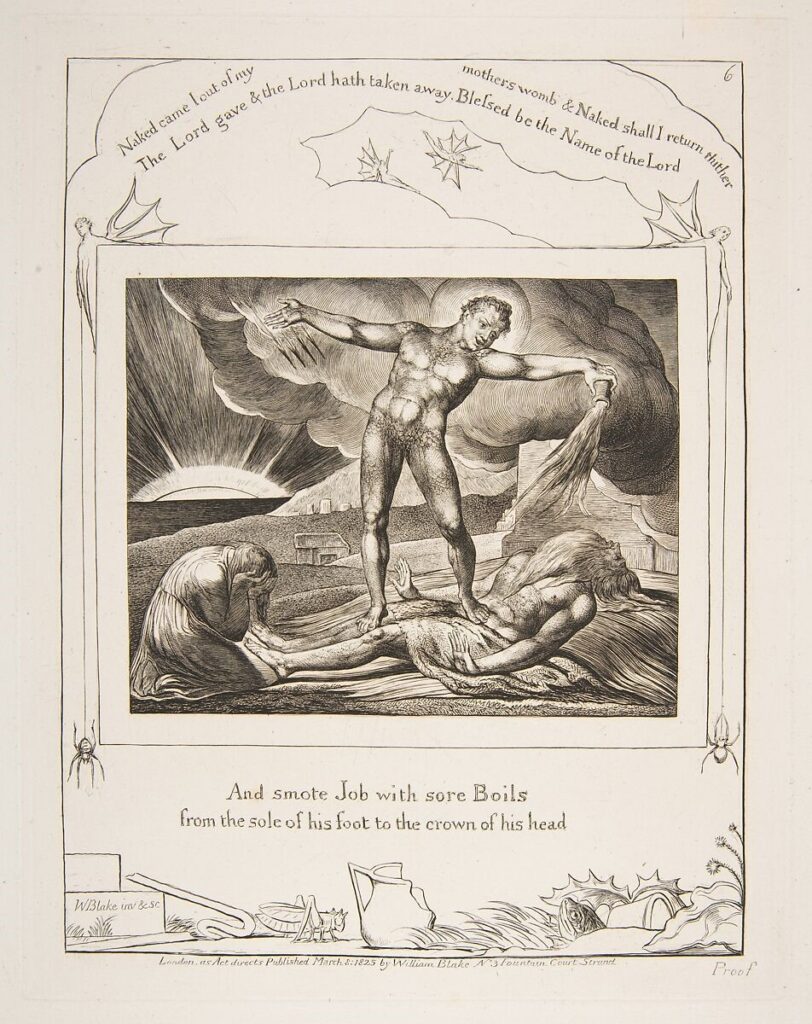

William Blake’s famous painting, Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils, pictures the devil pinning the Old Testament saint to the ground while afflicting his flesh. We see Job in great physical distress: neck bent—almost broken—backwards; fingers splayed stiffly; widened eyes wild with alarm. In his drawing of this same scene, Blake places it within a box, marked off and contrasted, as it were, with Job’s famously tranquil response to his plight which appears above the display: “naked came I out of my mother’s womb and naked shall I return thither. The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.” The quote paradoxically mingles distress with contentment, placing Blake’s work in a formidable religious tradition that for centuries has depicted saintly figures combining suffering with serenity.

Despite their prevalence down the ages, combinations like Blake’s are not to be found in bioethical literature on the nature of suffering, which everywhere appears as only distressing. It is fitting, then, that we do not find Blake’s paradoxical print but rather his painting, which lacks Job’s quote, on the cover of what is arguably medicine’s most well-known book about suffering, Eric Cassell’s The Nature of Suffering. The book jacket acts as a metaphor for an argument made explicitly by Cassell and implicitly by many others: that the sweet melancholies of the saints are an impossibility.

Yet what a break this is from so much earlier reflection on saints like Job, a point I came to realize in the course of my own illness. In the midst of my suffering, I coped by turning to the stories of other sick people; memoirs, biographies, and, as I waded deeper into history, hagiographies. Enthusiastically were the saints said to have embraced their illnesses, at times even courting them—licking lepers’ wounds, for example. None of it made any sense to me, so completely contrary was it all to my defeating experience. I did not understand the opportunity the saints saw in sickness. I found myself on the outside of a logic I could not penetrate. So, I turned to medical ethics for clarity but found little, with most authors assuming a position like Cassell’s.

What troubled me most was the facility with which bioethicists had arrived at such a monumental historical revision. Scarcely could an argument for it be found. It was beginning to look like we had rather forgotten that the traditions we denied were the same ones that gave us our acute concerns about suffering in the first place, as Charles Taylor and others have so persuasively demonstrated. What initially appeared to be a concerted revision proved little more than an accidental oversight.

A reconciliation with our history was therefore in order. This seemed especially pressing if we were to grasp the subjectivity with which most scholars characterize suffering. For, if suffering is idiosyncratic, then it must proceed from the vicissitudes of those undergoing it, making it all the more important to contextualize our theories. We must rediscover what our traditions have handed down to us, both in the questions that we think to ask about suffering and in the answers that seem most intuitive. Just as my attention was brought (dragged) to bear on suffering by something as unreflective and raw as sickness, so too is our intellectual inheritance rooted in the mangled stuff of history. To wade through that wreckage is both our responsibility and our privilege.

It was to tend to that lofty duty—however modestly—that I wrote my article.

Author: Charlotte Duffee

Affiliations: Human Flourishing Program, Harvard University Institute for Quantitative Social Science

Competing interests: None declared