By Max Drezga-Kleiminger, Joanna Demaree-Cotton, Julian Koplin, Julian Savulescu, and Dominic Wilkinson.

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) is moving rapidly. In the (recent) past, we could hide behind the knowledge that much of the ethical discourse around AI was in hypothetical terms – we were discussing what we should do in case technology progressed to the point at which it would be feasible to use AI to make decisions or fulfil tasks for us. Now, millions of people across the world are using AI, such as the large language model ChatGPT, for these purposes. And sure, using ChatGPT to do your year 9 maths homework may seem relatively harmless but clearly using this sort of AI to make medical decisions with life-or-death consequences has more ethical implications. However, there may be good reasons to use AI to make certain medical decisions.

How could AI be used to assist in liver allocation?

Let us consider the use of AI to allocate livers to those waiting on the liver transplant waiting list, which is clearly an ethically challenging area. Algorithms have been used to assist in liver allocation for some time and have been increasing in complexity. Since 2019, the UK has used the Transplant Benefit Score to allocate livers, a predictive algorithm which uses 21 recipient and 7 donor characteristics to predict a patient’s “survival benefit” from a transplant. Algorithms are useful for making empirical predictions, but they are also useful because they require us to make our values explicit and how these values should be weighed. The US is beginning to implement a new algorithmic organ allocation system where specific factors (such as urgency and predicted post-transplant survival) are chosen and given a weighting, and patients are then ranked based on those factors. More complex AI models have also been proposed for use in this area, which may be only a small step away from the current, accepted algorithmic allocation policies.

There are challenges of using algorithms and AI in ethical decision-making. A main obstacle is the difficulty of achieving sufficient agreement on normative values to distil them into programmable variables. There are two broad ways of programming AI for such decisions. A bottom-up approach could involve training AI on previous decisions to predict human choices. Alternately, AI could be programmed top-down, with either single or multiple objectives (or values) being explicitly programmed (such as the US proposal for organ allocation explained above). This would not necessarily need to be an AI program: after all, a simple rule-based algorithm could even be written on paper. However, this could be combined with more complex machine learning algorithms to predict relevant factors such as survival likelihood, which could then be input into the rule-based algorithm.

There is good reason to think that AI would be more accurate at making relevant predictions about implementing values and make decisions more consistently, impartially, and efficiently, although this is partly a contingent empirical claim. If it turns out that AI were less accurate or less consistent than human decision-makers, we should certainly not use it. However, the opposite also applies – if AI is more accurate/consistent, it may be ethically problematic to make decisions without using AI. There are also concerns regarding the use of AI for such applications. There is much debate about AI bias and the uninterpretable nature of AI decision-making processes. Broader concerns, such as the “dehumanisation of healthcare” and the idea that AI may miss some of the nuance involved in complex decisions, are also common.

Public attitudes

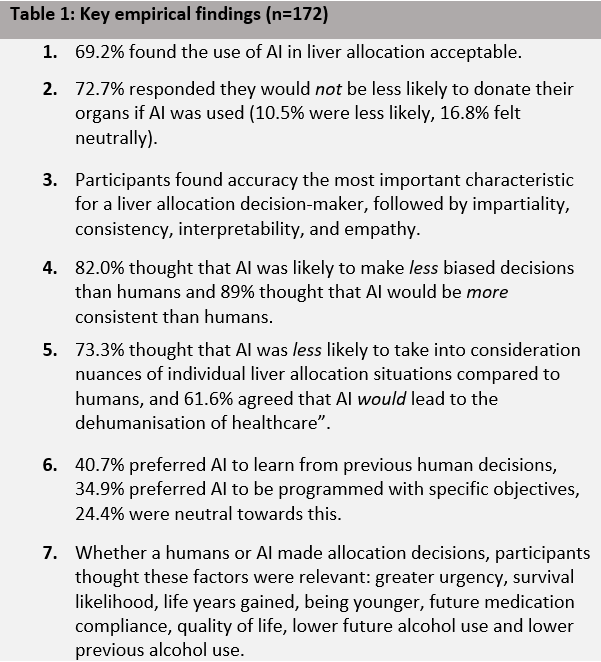

Public attitudes should also contribute to this discussion, particularly as the public controls the supply of organs via donation. In a recent paper not yet published, we examined UK public attitudes towards the use of AI in liver allocation via an online survey (key findings in Table 1). Of note, the first three findings indicate that the majority of participants support the use of AI in this context. This includes the importance participants placed on accuracy, consistency, and impartiality in liver allocation, compared to interpretability and empathy, areas where AI may have the advantage over human decision-makers. Furthermore, concerns voiced about nuances of decision-making and the dehumanisation of healthcare, indicate what issues may be important to address if AI is to be implemented. Finally, our findings also show that participants are ambivalent towards whether AI is programmed top-down or bottom-up, but that many of the factors which are used in current allocation practice around the world are still relevant in the public eye. Further work is required to assess how these allocation factors should be traded off, as well as to appraise some of the more contentious factors.

This survey was conducted in 2022, before the development of ChatGPT, and it would be important to assess whether increased public exposure to AI would decrease or increase acceptance of AI. However, generally it appears that the public thinks we should use AI in liver allocation and while the ethical issues are not conclusively resolved, this warrants further exploration.

So, when will this technology be ready to use? Well, even ChatGPT could technically allocate livers if we gave it a set of ethical values and weightings (top-down), or by asking it to summarise previous decisions (bottom-up). Clearly, this would require more rigorous testing of this technology (we tested this in ChatGPT and responses were inconsistent and at times contradictory), however it is clear that AI could allocate livers. Whether it should, remains to be seen, but these questions require answers soon.

Paper title: Should AI allocate livers for transplant? Public attitudes and ethical considerations [under review]

Authors: Max Drezga-Kleiminger1,2, Joanna Demaree-Cotton1, Julian Koplin3, Julian Savulescu1,5,6, Dominic Wilkinson1,4,6

Affiliations:

1. Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Oxford, UK.

2. Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

3. Monash Bioethics Centre, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

4. John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

5. Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia.

6. Centre for Biomedical Ethics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore

Competing interests:

Julian Savulescu is a Bioethics Committee consultant for Bayer and an Advisory Panel member for the Hevolution Foundation (2022-).