By Daniel Sokol.

When not working as a barrister, I teach medical ethics to doctors who are going through disciplinary proceedings. The majority are in trouble because of dishonest conduct. They may have lied on a job application, cheated in a membership exam, or forged a document for personal gain.

Medical Practitioners Tribunals have often noted the difficulty of remediating dishonesty. If a doctor harms a patient because they cannot put in a central line safely, then a practical course on this clinical skill should remedy the problem. But what is the equivalent intervention if the failure is not a demonstrable skill but a character flaw?

My goal was to find a way of helping doctors show their knowledge and understanding of honesty.

I discovered that some employers used ‘integrity tests’ to screen suitable candidates. However, these tests were focused on selecting productive and dependable employees and were of limited application to doctors. Personality tests, like the HEXACO Personality Inventory, were too broad in scope, assessing honesty but also emotionality, agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Following discussions with a number of testing experts, it was decided that a situational judgement test (“SJT”) that encompassed a range of clinical and non-clinical scenarios would be best.

I worked with Rob Williams, a Chartered Psychologist with over 25 years’ experience of designing tests. He recommended producing scenarios which asked respondents for their best and worst answers, with each correct answer scoring one mark.

I compiled 31 scenarios from a mix of my own cases and published cases of the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (“MPTS”). It was important, I felt, for the scenarios to be based on actual cases to avoid the criticism of a lack of realism.

Initially, doctors were asked what they would do if faced with the scenario. The feedback from my erstwhile PhD supervisor, Raanan Gillon, was that this would unfairly penalise those doctors who answered honestly. Rob Williams agreed.

Doctors are therefore asked what they believe is the best and worst answer. Although there is no guarantee that the respondents would act honestly in these scenarios, the test at least shows their capacity to distinguish right from wrong in the domain of truth-telling and honesty.

The SJTs were then sent to Simon Fanshawe, a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion consultant, to check for bias and other impropriety in the scenarios.

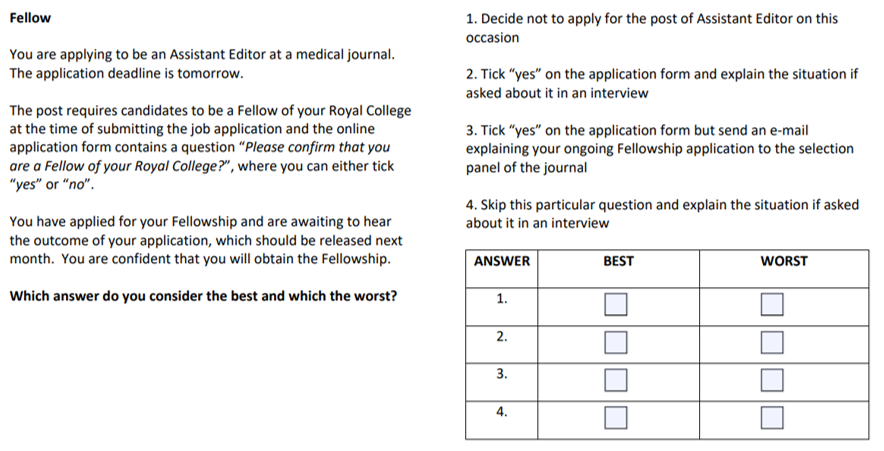

Next, the SJTs were tested on 12 doctors, who were not told that this was an honesty test. A modest payment was offered to each volunteer. After this exercise, the number of scenarios was reduced to 23. The dominant reason for removal of a scenario was that the circumstances were too unfamiliar for the average doctor. The second reason was excessive variation in the answers selected. Below is an example of a discarded scenario:

After the testing phase, I contacted the MPTS to ask if tribunal members could be approached to take the test. Their anonymous answers would represent what is “right” and “wrong”. The MPTS was reluctant and so I turned to UK-based professors of medical ethics who are also medical doctors. The medical requirement greatly limited the number of eligible respondents but it was necessary to avoid the likely criticism that the experts were unfamiliar with the realities of clinical practice and life as a doctor. A sum of £100 was offered for their participation. Six professors took part. Again, I did not present this as a test of honesty but described it as a tool to be used in the ethical training of doctors.

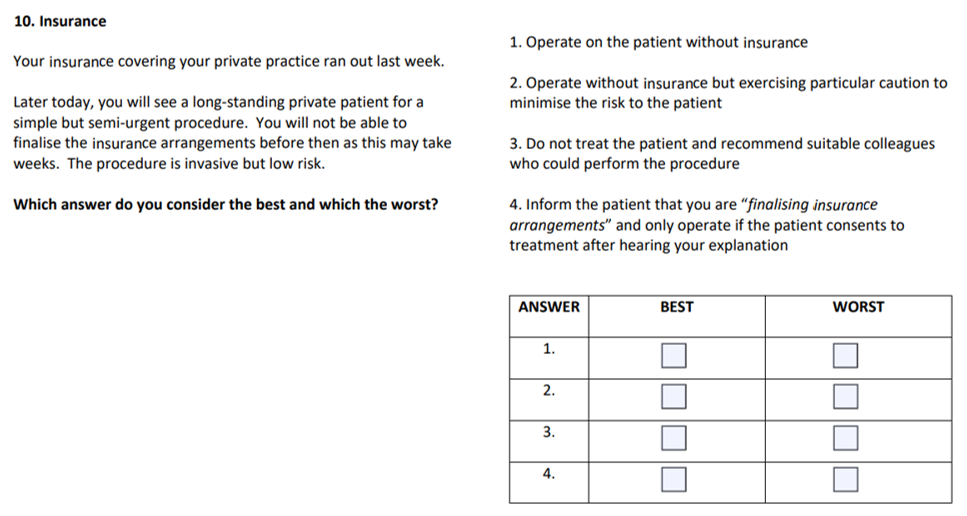

As a result of the professorial feedback, one scenario on practising medicine without insurance was removed. It was deemed of limited relevance to doctors without a private practice. The scenario appears below:

In the remaining scenarios, there was unanimous agreement in 32 answers and, for the remaining 12 answers, 5 out of 6 experts selected the same responses.

To the best of my knowledge, this test is the first honesty test for doctors. It cost approximately £4,300 to create, excluding my time and that of my assistant. It was funded privately. Everyone who has seen a version of the test has been asked to maintain strict confidentiality. Only my assistant and I know the collective answers of the Professors of Medical Ethics. To minimise the risk of a leak, the test is only administered in person.

At the end of the ethics training, I invite the doctors to complete the test. This takes approximately 25 minutes. Afterwards, we discuss each scenario, spending more time on those which the doctor found trickier.

Once they have completed the test, I invite the doctors to create their own scenario, based on their circumstances. This encourages them to think critically, and from a different vantage point, about their case. This genial idea came from Raanan Gillon, who told me that medical students at Imperial College had been asked to conduct a similar exercise in their ethics exams.

The feedback by doctors has so far been positive, with several observing that they had encountered some of the scenarios in their practice.

Recently, I approached a commercial research organisation to administer the test to 300 UK-based doctors. This would establish an average score, against which an individual doctor’s performance could be measured. However, as the proposed cost was close to £42,000, I was unable to implement this stage. It would be fascinating to administer the test to a large number of doctors and, indeed, members of the public. How would the scores of doctors undergoing disciplinary proceedings differ, if at all, from other doctors? Would doctors score higher in the test than members of the public? Would there be variations in test scores within the medical profession and, if so, why? It is an area ripe for empirical research.

Author: Daniel Sokol

Affiliations: 12 King’s Bench Walk Chambers, London, UK; medical ethicist

Competing interests: Daniel Sokol is the creator of the Situational Judgement Test

Social media account of post author: @DanielSokol9; Website