By Rasita Vinay and Annina Bauer.

On 13th April 2022, the third webinar for the Forum of Global Health Ethics webinar series took place, focusing on the issue of offering financial incentives to participants in health and breastfeeding research.

Offering financial incentives to research participants is a common practice in health research; however, its use remains controversial in some cases. The forum shared special focus on the ethical discussions surrounding financial incentives, particularly emphasising breastfeeding research. In this context, exploitation, undue Inducement, biases, and inequality are still highly debated topics, which may raise ethical concerns. In the following, we outline the key messages from the webinar by summarising the general views of the speakers on financial incentives.

There were 292 attendees present in the webinar from 104 countries, whose views on the topic were collected prior to the discussion, to be compared with post-discussion polling of the same questions.

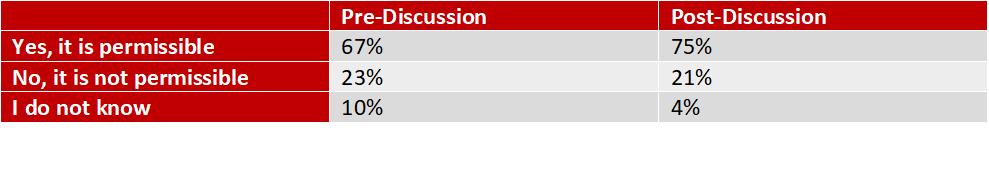

Table 1 shows the audiences views to the question, “Is it permissible to offer financial incentives (e.g. payments, vouchers, gifts) to participants in health research?”. After the discussion, the participants clearly showed a positive shift considering financial incentives to be permissible.

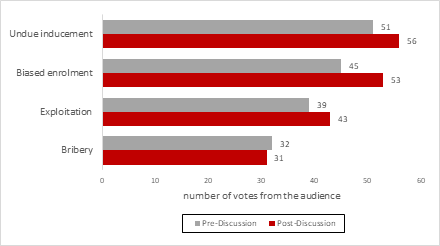

Figure 1 presents the topics determined by the audience to be the main ethical concerns regarding the use of financial incentives in health research. The poll revealed that undue inducement and biased enrolment were selected the most, followed by exploitation and bribery. The proportionality between the selected items were similar, before and after the discussion.

Table 1. Audience members views on whether it is permissible to offer financial incentives to participants in health research

Table 1. Audience members views on whether it is permissible to offer financial incentives to participants in health research

Figure 2. Polling results on the main ethical concerns regarding the use of financial incentives in health research

What is the current state of research on the use of financial incentives?

At present, there is a general need to optimise research procedures so that vulnerable populations can be safeguarded from existing injustices and social needs. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and other ethics committees often stress that participants must be rightfully compensated for their time and effort. However, there are growing ethical discussions surrounding incentivisation, in particular of undue inducement, exploitation, biased enrolments, as well as bribery. Financial incentives can be seen to encourage participation in research studies; however, they can also bring harm, especially to regions with socioeconomic deprivations, i.e., low-income, or low-middle income countries (LIC or LMIC, respectively). However, it is important to note that also vulnerable populations (i.e. racial and ethnical minorities, migrants or socioeconomic disadvantaged groups) from high-income countries (HIC) can be affected by this problem. Despite a lack of consensus within the literature, there are obvious trends emerging from these regions, which indicate that money is a quick motivator and incentive for participation.

Within breastfeeding research, financial incentives can be seen to increase the prevalence of breastfeeding rates, however, if breastfeeding is seen as a parental duty, then is there a need for incentivisation? The Convention on the Rights of a Child (1990) stipulates that there should be appropriate measures by the community to:

“Combat disease and malnutrition … through the provision of adequate nutritious foods, clean drinking water and health care”

It must also be considered that some families may only be seeking support or resources rather than financial incentives, for which they might not otherwise have equitable access. Other reasons that could provide altruistic reasoning for participation include curiosity, acquiring scientific knowledge, gaining access to medical treatment, perceptions of receiving additional attention from healthcare workers or a presumed therapeutic benefit. Monetary incentives can be seen as problematic for undue inducement, which would ultimately undermine an individual’s autonomous decision-making to become more financially motivated. Not only is this an essential element of receiving informed consent, but it could also lead to participants purposely taking excessive risks to remain in the study or overestimating the benefits as opposed to the risks. However, undue inducement can also be present in the form of non-financial incentives, for instance, receiving treatment in clinical trials. Participants in phase I clinical trials would never receive any direct medical benefits, and therefore it might be possible that incentives could play a major role in the participant’s enrolment. In phases II and III, participants would often receive medical or therapeutic benefits, which would then become the leading factors for participation. In Switzerland, for instance, financial incentives are not allowed when a clinical study is expected to have a direct benefit on participants. Hence, the discussion on whether study participants are being paid too much or too little doesn’t apply in such cases.

In order to avoid issues of inducement, researchers are being pressed from the international community to find alternatives for instituting behavioural changes. For how long can researchers continue to sustain financial motivations to promote positive behaviours around breastfeeding? The risks that this would have for local economies, because of the infusion of financial incentives, could prove to be destabilising.

Can we apply an economics lens to health and breastfeeding research?

While there are mixed findings in the literature, some studies showed that financial incentives can influence participants’ behaviour. However, aren’t individuals always better off receiving money than not – even if this is a minimal amount? Or are there situations in which money is actually a bad thing? For instance, when a research intervention is known to cause a direct benefit to participants, it becomes difficult to argue whether they are being paid too much (undue inducement) or too little (exploitation). This would be because paying too much could result in higher participation, therefore an increased number of individuals would receive a beneficial health intervention. If you paid too little, it could still be argued that participants received a positive health intervention, and therefore, a monetary incentive would not be the only benefit, appropriately justifying the smaller amount of money distributed to participants. Alternatively, when benefit from health interventions are not guaranteed, a paternalistic view would suggest that the participants enrolled in the study just to receive the financial incentive, however, they didn’t receive the benefits assumed or are worse off from the intervention.

We can also bring an economical principal-agent problem to health research, in which the researcher would be the principal and the participant as the agent. The problem here would be that there is an asymmetry in the information disclosed, where the researchers might have much better understanding or knowledge about the potential risks or uncertainties involved, while the participants may not. If you introduce high incentives to such scenarios, it would be brought to question whether the welfare of the participant is changed. While high incentives may increase participation numbers, there is a likelihood that it would reduce the attention a participant may pay to the risks described by the researcher. Additionally, there are also strong incentives for the principal, or the researcher, which would be to conduct research and attain a publication. This might also encourage researchers to downplay the risks or uncertainties, or altogether fail to provide this information to participants.

What are the other ethical concerns of incentivisation?

Exploitation

Exploitation involves taking unjust or unfair advantage of a person or a group of people. This can be seen in health research when you provide financial incentives to human participants, where there are unfair advantages to individuals or groups in a transaction or relationship. Additionally, there are questions of exploitation when involving research participants from vulnerable populations, as these participants may not be in a position to make decisions for their best interest. There are also trends where participants from LICs disproportionately participate in no-benefit and high-risk studies. In the context of breastfeeding research, it brings to question whether mothers are also exploiting their infants by enrolling them in research studies?

Biases and inequality

Issues of biased enrolment, as well as other ethical risks (e.g., undue inducement, exploitation, bribery), can threaten a study’s integrity. Individuals from low socio-economic backgrounds are normally more likely to participate in studies for monetary benefits. However, it can also be assumed that studies which do not offer incentives can still be biased in their recruitment, where individuals who may not need money are more likely to become participants – especially those from a stronger socio-economic background.

Unequal payments for participation in similar studies is also another ethical issue to be discussed. There are marked differences in the amount of payments offered as incentives in different parts of the world for similar (or the same) research. In LICs or LMICs, only the out-of-pocket costs for participants’ attendance to a clinical trial visit is considered for compensation. This is usually around USD $5-10. In high-income countries or wealthier nations, the amount of the incentives observed is around USD $100, sometimes more. Such differences can threaten principles of equity.

What can be reasonably expected from future researchers or ethics committees?

Ideally, there needs to be identification of who is responsible for determining if, and how much, financial incentive needs to be offered. IRBs sometime consider financial incentives to be coercive, but conceptually, coercion involves the force, intimidation or the threat of harm, and money does not bring any harm to individuals, but can rather be a potential benefit. Typically, decisions on financial incentives would need to be based on the assessment of the benefits and risks of the study, the time invested by participants, economic evaluations of the demographics and communities involved, as well as the ability of the incentive to actively encourage participation in the research. Further, ethics committees also need to come up with different ways to monitor the research that was promised, with the research that is conducted. Currently, research carried out on the field is done in good faith, but there needs to be systematic processes of ensuring that research continues to be ethically implemented and reported. It would also be worthwhile to create a system in which stakeholders also have the opportunity to exchange views and ideas for alternatives to monetary incentives.

There is also the need for further research to understand the relationship between demographic variables (i.e., income, race, ethnicity, and education), and the influence of money on the willingness to participate, the perception of risks, and the participants’ willingness to lie.

ABOUT THE WEBINAR

The webinar was jointly organised by the Institute of Biomedical Ethics and History of Medicine (University of Zurich), The Swiss Medical Weekly, The Global Health Network (University of Oxford) and LactaHub. This event complemented the first LactaWebinar that took place in March 2022, offering an introduction and conversation on EFBRI – An Evolving Ethical Framework Informing Breastfeeding Research and Interventions, whose summary can be found here.

The forum was co-chaired by Nikola Biller-Andorno (Co-creator of EFBRI; Director, Institute of Biomedical Ethics and History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Switzerland) and Tania Manríquez Roa (Coordinator of the Forum for Global Health Ethics, University of Zurich, Switzerland). The panel of experts consisted of Mary Ani-Amponsah (Researcher, University of Ghana; Country Representative for the Council of International Neonatal Nurses, Ghana), Farah Asif (Clinical Research Administrator, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre, Pakistan), David Yanagizawa-Drott (Professor, Department of Economics; Managing Director, LRF Centre for Economics and Breastfeeding, University of Zurich, Switzerland) and David B. Resnik (Bioethicist, National Institute of Health, USA).

A recording of this webinar is available here.

Author names: Rasita Vinay1 and Annina Bauer1,2

Affiliations: 1. Institute of Biomedical Ethics and History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Switzerland

- Clinical Trials Centre, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Competing interests: None to declare

Social media accounts: (Twitter) @uzh_ibme

(LinkedIn – Rasita) https://www.linkedin.com/in/rasita-vinay/ ;

(LinkedIn – Annina) https://www.linkedin.com/in/annina-bauer-3280501b5/