By Charlotte Blease, Catherine DesRoches, Maria Hägglund, Adam Hayden, Hanife Rexhepi, & Liz Salmi

Most of us now use the internet to check the health of our bank balance. Worldwide, however, the majority of patients still cannot inspect their actual healthcare records online.

From April 5 in the USA the law changed. With few exceptions it is now mandatory to offer patients access to their electronic health records, including the very words written by clinicians – a practice known as ‘open notes’. In Scandinavia, this innovation is already advanced.

But do patients really need access to their health information, or should electronic health records be the sole preserve of physicians? We explore this question using our own case studies.

Case 1: “Compelled to Google”

In the Spring of 2018, my [CB’s] partner – a journalist on a UK national newspaper – was diagnosed with stomach cancer, a moment we’ll never forget. As a highly experienced writer and interviewer – never without a notepad and pen to dash off shorthand – beyond the actual diagnosis, he could recall scarcely any details of that consultation. As a result, between oncology visits, he requested copies of his clinical notes – several times. Awaiting more info, and feeling mystified and exhausted, both he and I spent sleepless nights on Google in a desperate attempt to try to understand his diagnosis.

Case 2: “The post-it note”

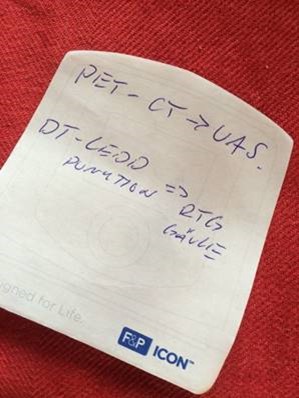

When an x-ray revealed that my [MH’s] father’s lungs were full of metastatic tumours, I took on the role of tracking all referrals and contacts with the different healthcare providers. In Sweden, I’d experienced the benefits of reading my online clinical information, but the region where my father lived didn’t yet provide such access. At one visit, after asking for copies of his referrals, we were eventually offered scribbles on a post-it note. On good days, I blame the lack of proper technical solutions, on bad days I cannot help but discern an unwillingness to provide us with the information we so desperately needed.

The post-it note (photo credit: Maria Hägglund)

Case 3: “What patients say and what doctors hear”

“If there were something seriously wrong, you’d be in much worse shape,” a general practitioner reassured me [AH]. My gut told me otherwise. Six months later, and 15 months after first symptom presentation, I was sent for an MRI scan that revealed a 71mm primary brain tumour: glioblastoma. Turns out that I was, in fact, in much worse shape. I had tracked my own symptoms for months. Access to my clinical notes might have afforded an opportunity to compare, as Danielle Ofri, MD writes in her book of the same title, “what patients say and what doctors hear.”

Case 4: “Averting medication error”

In the fall of 2019, my [CD’s] elderly aunt fell and fractured her pelvis. Arriving at the hospital emergency department, a nurse was preparing to give my aunt her “regular medications.” “How do you know what medications she takes?” I asked – knowing that C was not cognitively capable of remembering her many medications. “I looked in our EHR,” said the nurse. The medications listed in the hospital’s EHR were from a hospitalization two years prior and woefully out of date. It was only because I was able to access all of C’s health information through a patient portal that I was able prevent a serious medication error.

Case 5: “Above average”

After my hospital launched open notes, I [LS] read someone had added above average health literacy to my record. I smiled at the compliment, but a nurse practitioner friend had a different take all together. “That’s not a compliment,” she said. “That’s a warning to watch what you say around this patient.” I stopped smiling. I had heard clinicians sometimes use coded language in patient records but never thought it would apply to me. How could being a savvy, engaged patient be a threat? Might clinicians be forming preconceptions about me, or dumbing down their communication to avoid discussion or disagreement?

Case 6: “Trust through transparency”

In 2015, I [HR] was diagnosed with a brain tumour. This distressing period of my life led to anxiety and depression. I started seeing a therapist. During our first meeting she recommended I access my mental health clinical notes. By reading her words, I began to better understand my depression. The meetings with the therapist together with the clinical notes helped me develop self-care strategies. Trust in my therapist also increased. By reading the notes I was able to identify misconceptions that occurred during our conversations and correct them at the next meeting.

In our paper, “Patients, clinicians, and open notes: Information blocking as a case of epistemic injustice” we go beyond personal case studies. Drawing on a range of international surveys and findings we explore the practical, ethical, and patient safety consequences of denying individuals online access to their clinical notes and records.

Paper title: Patients, clinicians, and open notes: Information blocking as a case of epistemic injustice OPEN ACCESS PUBLICATION

Authors:

Charlotte Blease; Twitter: @crblease

Catherine DesRoches; Twitter: @cmd418

Maria Hägglund; Twitter: @mariahagglund

Adam Hayden; Twitter: @adamhayden

Hanife Rexhepi; Twitter: @haniferexhepi

Liz Salmi; Twitter: @TheLizArmy

Affiliations:

CB, CD, LS: Division of General Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA.

CD: Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

MH: Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University and Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden.

HR: Department of Informatics at the University of Skövde, Sweden.

AH: Indiana University, Indianapolis, USA.

Competing interests: None.

Social media accounts of post authors: @crblease; @cmd418; @mariahagglund; @adamhayden; @haniferexhepi; @TheLizArmy