By Thibaud Haaser

The Covid-19 constitutes a real global crisis, going beyond the sole medical dimension. Medical, socio-economic or educational issues have highlighted the need to identify specific therapeutic or preventive agents as soon as possible. The necessity to build reliable medical knowledge is part of the response to such a crisis. Although the crisis is not over yet, we can already reflect on what should or could have been done in handling this unexpected episode. Indeed, similar situations may arise in the future and there is an ethical requirement to identify what might be the most appropriate way to handle such a crisis.

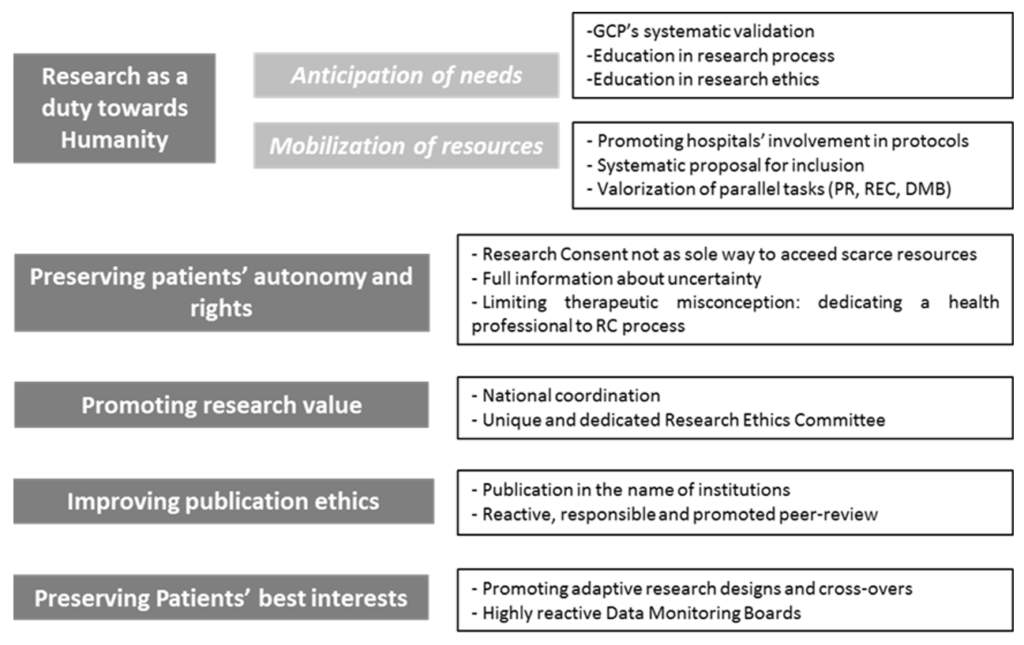

Our ethical analysis is based on the double agency of physicians, at the same time health professionals, but also biomedical researchers facing an unknown pathology. Covid-19 pandemic has stressed out the close entanglement between care and research in the case of an emergent and pandemic infectious disease. Indeed, scientific knowledge is built alongside the realization of cares of the first patients, with the same persons (health professionals) having simultaneously two roles. In such a context, ethical frameworks of both care and research are simultaneously deployed and sometimes may be conflictual. In this post we identify five ethical imperatives and we also propose some practical ways to implement those five ethical imperatives.

Reaffirmation, adaptation or implementation of ethical imperatives in times of pandemic

First, facing an emergent infectious pandemic disease, the need to identify efficient and secure therapeutic should be identified as an imperative for physicians. The specificity of an emergent infectious disease imposes to underline the social responsibility of physicians which may also consists in building knowledges in a context of high uncertainty. Improving the possibility to gain medical knowledges appears as an ethical requirement . Physicians are called to escape from their sole duties towards patients and to consider themselves as major stakeholders within society (see the forthcoming article from AJ London). This duty towards the global community takes the shape of participating to biomedical researches. This activity must be promoted and seems to be as essential as (but not more than) duties towards patients.

Thus this imperative needs anticipation of the needs and mobilization of the means during crisis. Anticipation should be assured by preparing physicians to their possible role of researchers in case of new global medical crisis. Systematic validation of Good Clinical Practices and repeated education in research process (especially reporting of adverse events) are means for such a preparation and in research ethics (especially concerning consent procedure in case of cognitive impairment or high socio-educative vulnerability). This would aim to reduce as much as possible the adaptation time of physicians in a time of emergency for research. This preparation phase should also concern other health professionals including nurses. Mobilization for research during crisis consists in the promotion and the facilitation of care institutions’ involvement in clinical trials. Systems of valorization (even financial ones) should be thought in order to promote hospitals’ participation to research (including university and non-university hospitals). At a smaller scale, a systematic proposal to integrate clinical trials should be considered for every patient. This can be possible only if research protocols have been locally implemented which reinforces the need for hospitals’ involvement. The systematical proposal does not mean to impose participation to patients and it cannot be seen as the only way to access to possibly scarce resources. The only aim for systematic proposal is to improve recruitment.

Duty for research as a duty towards humanity should also include professionals’ involvement in all parallel tasks ensuring the quality of biomedical researches. Commitment in specific Research Ethics Committees, participation to Data Monitoring Boards or peer-reviewing are as essential as the research process itself. They also allow not directly-involved health professionals to participate to a global effort (especially in Research Ethics Committee or Data Monitoring Boards). Those tasks must be rewarded in physicians’ career as genuine parts of the needed mobilization. In case of pandemic, these parallel tasks could not be interpreted as inferior or secondary ones. Mobilization for research requires the recognition of the stakes and the value of those tasks and specific dedicated times for physicians.

The second imperative is to reaffirm the need to respect patients’ autonomy and rights. Consent remains the cornerstone of biomedical research and cannot be waived in clinical trials. Even with a systematic proposal, patient’s consent cannot be considered automatic. Two specific points must be addressed. First, physicians cannot make research consent be the only way to benefit from access to scarce medical resources. Rewards to research consent is an ethical imperative but rewarding through priorization questions the voluntariness of consent. In context of scarcity of some medical resources, research consent could become a “deal that cannot be refused”. An ethical reflection must be done to ensure that a refusal to consent (or a withdrawal) could not become a condemnation to a restricted access to medical resources. Second, informed consent documents should have to integrate full information including the specific context of uncertainty. With an unknown disease, uncertainty must be directly addressed. As usual medical research, the need of randomization must be clearly explained, as the possible need of a placebo. In case of refusal, patients must be informed they will benefit form the best treatment their physicians could identify, but with a subjective choice, because of this uncertainty. Biomedical researches must be presented as the way to avoid this scientifically-based, but still remaining arbitrary choice of physicians.

Those two precautions participate to address the major problem of therapeutic misconception which has to be very carefully tackled in this context. Duty for research strengthens the double agency of physicians. The necessary distinction of those two approaches requires attention and adaptation in research consent process. A concrete proposal could be to identify in every unit a health professional (physician or nurse) who would be specially implicated in the information and consent processes. Dedicating a professional to this specific task can be objectionable in times when health systems are in tension. However, such a distribution of roles ensures the quality and validity of research consent. It also makes the other health professionals focus on theirs care activities.

The third imperative is that no consent could be wasted. We mean that the quality and value of research become major ethical imperatives in a context of pandemic. The highest methodological and ethical criteria must be achieved for every single consent. Researches with forthcoming unreliable results for methodological reasons should be avoided. The value, and more specifically, the social value and usefulness of research should be part of the ethical analysis of protocols. To achieve this imperative, two means seem essential. Research must be coordinated at a national and even international scale in order to avoid research cacophony. Health systems should insure this coordination as they encompass public and private research institutions. The procedures and means to achieve this goal of coordination must be thought previous to possible future crises as COVID-19. Coordination at national or international scales through health systems would also ease collaborations with pharmaceutic industries as personal or institutional conflicts of interest would be minimized. Trustfulness of health systems from both physicians and patients should be maximized in such stressful contexts. Representation of patients in debates in order to make live a concrete health democracy would strengthen people’s trust. An effective transparency of procedures will ensure physicians’ trust, minimizing the temptation to implement local and probably less relevant or powerful studies. The second mean would be to make value of research a specific topic of Research Ethics Committees’ analysis. This is all the more important that patients may consent because they feel ought to participate to a global mobilization of society: thus involving them in non-reliable studies would be like disrespect for their belief in the social value of research. A unique national Research Ethics Committee could be created in order to ensure a convergent point for all studies focusing on the emergent topic. It would also lead to faster and more consistent ethical analysis. With a unique structure for ethical analysis, the value of research will be more easily evaluated: irrelevant, redundant or unreliable studies would be directly identified.

Fourth, publication ethics should also be addressed. The current “publish or perish” state of mind in Medicine should be minimized (15). The main goal should be to reduce as much as possible personal interest of physicians in research publication. Furthermore, covid-19 pandemic has shown us the propensity of some physicians or researchers to seek light and create useless and even counter-productive debates. Thus, the personification of biomedical research into a few individuals should be kept to a minimum. Clear rules in authorship must be thought and they may include publication under the sole name of the coordinating institution (e.g., health systems). This proposal must not be understood as a punishment or a privation from a legitimate reward for health professionals. It is above all a way to minimize the temptation to initiate research and publication for personal interests first. Participation to high quality clinical trials must still be promoted in physicians’ CV (as participation to scientific boards, Data Monitoring Boards or peer-review process). This proposal participates to the recognition of the overwhelming duty for research and it also underlines physicians should first act in the name of their social and even humanitarian values.

Furthermore, high quality reviews should be committed through fast but exigent and respectful peer-review process. Retraction of publication is a failure for research. It is also a very bad signal towards society, leading to potential patients’ mistrust and to possible interference in patients’ will to consent to research. As we said, peer-review must also be interpreted as duty of physicians during a pandemic, and so it must be recognized. With research coordination (limiting studies to the sole most relevant ones) and evaluation of protocols’ value, the peer-review process would probably be eased.

The last imperative is to keep on preserving patients’ best interests throughout research procedures. With emergent diseases, the fast evolution of knowledges makes the definition of “best interests” very changing (sometimes from a week to another). This requires adaptation as much in cares than in research protocols and it must be integrated in research designs. Thus adaptive research designs (as platforms studies for example, enabling to pool placebo or multiple therapeutic arms in a single large study) should be privileged. Likewise, cross-overs between therapeutic groups, or from a control group to an interventional group, have to be promoted within research protocols. Data Monitoring Boards must be extremely reactive and monitoring has to be as frequent as possible, in order to close or continue inclusions in experimental arms if necessary. Their total independence must be guaranteed. A large-scale coordination of research would help this imperative to be applied in order to avoid keeping on including people in irrelevant therapeutic arms.

Conclusion

Our proposals are a mix of reaffirmation of ethical duties (preserving the autonomy and rights of patients, preserving the best interests of patients, evaluating the value of research) and the implementation or adaptation of new ones (research duty understood as duty to humanity, ethical imperatives in scientific publication). If no exceptionalism can be tolerated, certain adaptations are essential to stick to the reality of the needs but also of the possible deviations or risks. Our proposals also include concrete means to achieve these objectives. While clearly open to criticism, our practical proposals seek to clarify and implement ethical imperatives in real life. Ethics in times of crisis cannot be reduced to a single reaffirmation of principles. It must include a practical dimension to be understood, promoted and respected. The most salient issue is to protect patients, but also doctors and all healthcare professionals from confusion as to the nature of their roles during a global pandemic crisis. This involves in particular managing the double agency of physicians in an exceptional context. In such a context, no hermetic barrier could be lifted between care and research because they are implemented concomitantly in the face of a new disease. It is about thinking and bringing to life two essential and complementary approaches with their own logic and ethical imperatives.

Author: Thibaud Haaser

Affiliations: Ethics and Research Centre, University of Bordeaux, France

Competing interests : none

Social media accounts : twitter @HaaserThibaud