By Rose Glennerster and Nathan Hodson

Last month 20 British doctors returned the medals they received in recognition of their work during the Ebola crisis. They were protesting against the extensions of the government’s “hostile environment” policy into healthcare, highlighting the case of Albert Thompson, a Windrush migrant who had lived in the UK for 44 years who was charged £54,000 before being treated for his advanced prostate cancer. They argued “the government that rewarded us for crossing borders to help patients is increasingly creating borders between us and our patients, culminating in the 70th anniversary of the NHS having the most restrictive and regressive charging regulations in NHS history”.

Access to secondary care (hospital) services in the UK has been made harder by the introduction of strict regulations, prompting vociferous objections from doctors. However, everybody, regardless of immigration status or housing, is entitled to access primary care (general practice) free of charge (although the government has hinted at plans to introduce charges in the future). In this post we suggest that policies ostensibly intended to restrict access to secondary care may create barriers to accessing primary care by confusing patients about their eligibility and confusing professionals about who they ought to be treating.

‘Hostile Environment’

The 2014 Immigration Act sought to limit the factors that “draw illegal immigrants to the United Kingdom”. Following its introduction, the Home Secretary at the time told the BBC: “What we don’t want is a situation where people think that they can come here and overstay because they’re able to access everything they need”. The explicit intention was to be “tougher on those with no right to be here” and create a “hostile environment” for unlicensed migrants in the United Kingdom. This threatened to widen healthcare inequalities by creating barriers to access to healthcare amongst vulnerable populations, including refugees and asylum seekers amongst others.

Current law and guidelines:

Under sections 38 and 39 of the 2014 Immigration Act, a surcharge was introduced “for certain categories of temporary migrant” on applying for entry clearance to the UK. Amendments to the Act meant that from April 2015 all those seeking to stay in the UK for more than six months were required to pay a healthcare surcharge of £200 per year (£150 for students).

Also under the amendments, residents with “indefinite leave to remain” would be charged for secondary care services outside urgent Accident and Emergency care. The majority of migrants were required to pay additional surcharges of £1000 alongside VISA fees and obtain a Biometric Residence Permit from their post-office within two weeks of arrival, which would be pre-registered with the NHS.

In 2015 the Department of Health introduced the ‘Migrant and Visitor NHS Cost Recovery Programme’, giving NHS staff responsibility to ask for proof of identity and immigration status before providing care. The same year, NHS Counter Fraud Service (CFS) issued guidance to GP practices on patient registration fraud, advising “It is important to ask all new patients (whether registering permanently or temporarily) to provide identification upon registering” and “a practice can, if it wishes, ask for proof of identification and other documents.” This is slightly misleading because, although a practice may ask to see identification, the inability to present identification is not, contrary to NHS CFS’s implication, reasonable grounds for a practice to deny registration. The law does not currently preclude anyone in England from free access to primary healthcare.

In 2015 and 2017, NHS England issued guidance reiterating the universal entitlement to primary care, free of charge, regardless of nationality or immigration status. This guidance has been welcomed by the authority on GP registration in England and restated by guidance from the British Medical Association and the Care Quality Commission:

“No documentation should be required in order to register with a GP. Overseas visitors have no legal obligation to provide proof of identity or immigration status; however, asylum seekers may be able to provide an ‘application registration card’ (ARC) provided by Immigration Services”.

Access to Primary Care

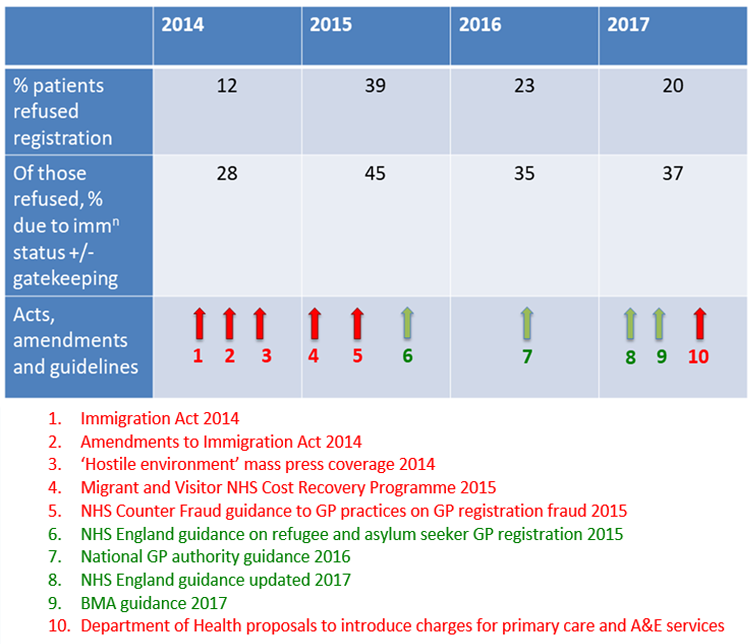

The proportion of people being refused GP registration has changed between 2014 and 2017. We analysed the trend in refusals based on gatekeeping behaviour and immigration status following the introduction of legislation and a ‘hostile environment’ towards unlicensed immigrants in the UK. The table below shows the proportion of patients being refused GP registration between 2014 and 2017 and of these, those refused due to gatekeeping behaviour or immigration status.

The figure presents data compiled from 4 separate studies (2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017) conducted by Doctors of the World UK (DOTW) and demonstrates their relationship with key regulations, amendments and guidelines, including the original legislation and the subsequent guidelines that sought to clarify the law for GP practices. DOTW collected data pertaining to the number of refusals and the reasons for refusal caseworkers visited GP practices across London to help register their clients (refugees, asylum seekers, unlicensed immigrants, children, homeless people, and victims of torture, trafficking, domestic violence, or sexual violence).

The figure shows the proportion of registration attempts made by the caseworkers that were refused and the proportion of those refusals that were due to either gatekeeping behaviour by reception staff or immigration status. Gatekeeping behaviour was recorded as a reason for refusal if front line staff exhibited obstructive behaviour (e.g. ‘unable to speak to person responsible for registration’ or ‘receptionist could not confirm registration would be allowed’).

Sample sizes varied due to varying population sizes accessing DOTW services, but the studies can be compared over time as the methodology (including selection criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria) remained constant. The sample population is made up of people accessing DOTW services, representing only a small proportion of this patient group. Furthermore, the attempts at GP registration were not made by the patients themselves (where other barriers such as fear of arrest and language barriers may come into play) but by DOTW caseworkers who were acting as their advocates. Therefore the proportion of people from these at-risk groups who are refused GP registration is likely to be much higher in reality.

Findings

Following the introduction of legislation and surrounding press coverage, the number of people being refused registration to GP surgeries has risen and remained high. Multiple subsequent guidelines re-iterating the right to primary healthcare appear not to have completely counteracted the exclusionary rhetoric. Although they have been associated with a partial improvement, both ‘refusals’ and ‘refusals due to gatekeeping’ remain much more frequent than they were prior to promotion of a hostile environment. In 2017, over one quarter of DOTW registration attempts were refused due to the gatekeeping behaviour of practice staff and one in ten were rejected due to immigration status, suggesting significant confusion regarding NHS registration guidelines amongst GP practice staff.

General Practice Websites

Although BMA guidance is clear that failure to provide documentation is no reason to deny registration, GP surgery websites reveal confusion about who is entitled to primary care. One typical website from a practice in London says, “Eligibility can be quickly confirmed from your address so please provide proof by way of a recent utility bill or bank statement. We also require one form of photographic ID (a valid passport).” It is inaccurate to claim that a valid passport is a requirement for registration with this practice, but the guidelines seem not to have reached the member of staff who wrote the website.

Another practice website in London states, “You will need to provide your NHS (National Health Service) number, your previous GP details, place of birth and proof of your current address; If you have come from abroad you will need to show us your passport, ID card or Home Office correspondence.” Imposing additional demands on people “from abroad” could risk breaching the 2010 Equalities Act and NHS London warns practices against enacting such policies which “could lead to legal action against them”. It is evident that key messages about registration policy are failing to reach frontline decision-makers.

Unintended Effects

There is evidence that new rules restricting access to secondary care have unintended effects; it cannot have been deliberate that Albert Thompson, the Windrush migrant, was excluded from treatment after 4 decades in the UK. This shows that the policy has been designed poorly and implemented carelessly.

These regulations also appear to have had unintended effects on access to primary care, not only among refugees but among wider society, potentially including people who do not drive, travellers, people in shared accommodation, students, renters, and anybody who has not paid £75.50 for a passport.

What we do not know is whether confused receptionists are denying registration to more patients or whether patients themselves are being confused out of registering. What is clear is that a well-publicised hostile environment in NHS hospitals has coincided with an increase in the number of asylum seekers, refugees and unlicensed immigrants being refused GP registration (particularly for reasons based on immigration status and gatekeeping behaviour) and that some GP practices are mistakenly denying registration to people without specific documents and declaring this policy on their websites. Somewhere along the line, many people who are entitled to primary care come to believe that they are not.

Conclusion

Given the apparent disconnect between the guidelines and the frontline, it is unlikely that further reiteration of the right of all in the UK to access primary care irrespective of documentation would be sufficient to prevent erroneous refusals of registration. Nevertheless guidelines pertaining to primary care, such as the NHS Counter Fraud Service guidelines, should never contradict the NHS Standard Operating Principles. A penalty system for practices illegally refusing patient registration would also be difficult to implement as the guidelines are complex, the outcomes are often hidden, and no penalty framework exists at present. Instead, a more successful approach may be a campaign of education and training directed at both general practitioners, administrative and support staff. Currently there is still work to be done to counteract the hostile environment and clarify the vital role of frontline staff in welcoming hard-to-reach patients.

Authors:

Rose Glennerster, Foundation Doctor, Royal United Hospital NHS Trust.

Nathan Hodson, Foundation Doctor, Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust. Twitter: @NathanHodson

Competing interests: None declared.