By Iain Brassington

Stanley Cavell died a few days ago. He is, I suspect, not widely known among medical ethicists, and is cited less. Fair enough: medical ethics wasn’t his thing. It’s a shame, though, because his work did strike me as being worth getting to know. This is not to say that I was familiar with it – I wasn’t, beyond the odd snatch – but he was someone whom I meant, and mean, to read more.

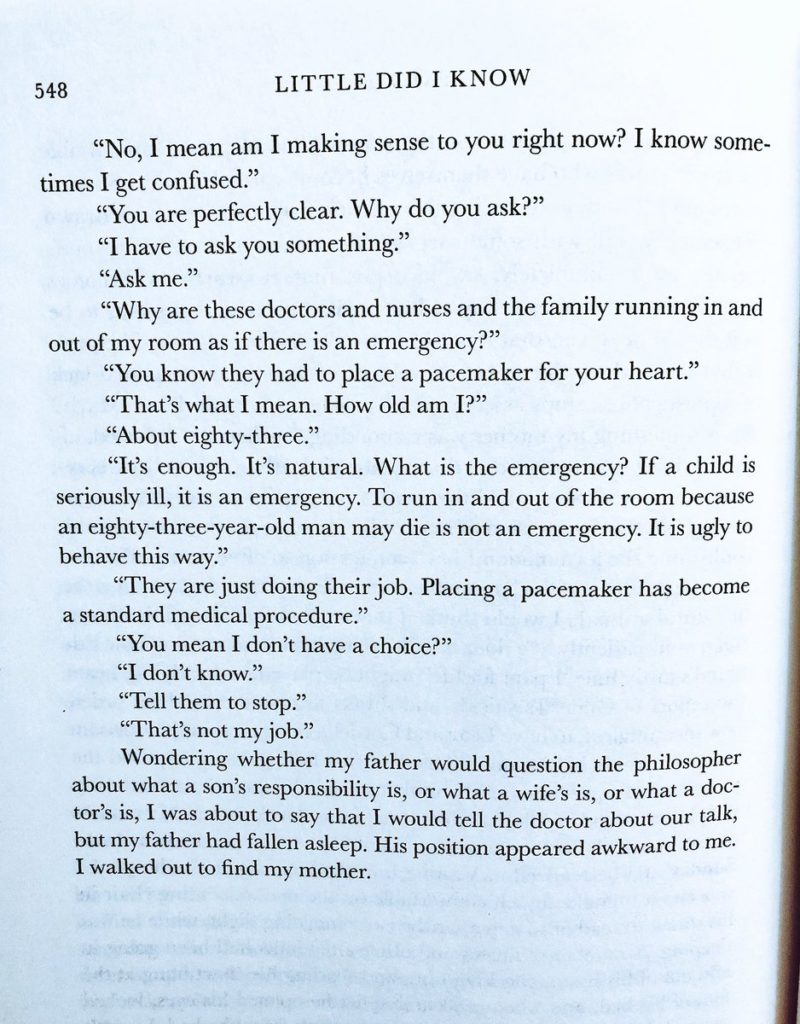

I mention him here because of something that Martin O’Neill posted on twitter: a scan of a page from his last book, 2010’s Little Did I Know:

“Why are these doctors and nurses and the family running in and out of my room as if there is an emergency?”

“You know they had to place a pacemaker for your heart.”

“That’s what I mean. How old am I?”

“About eighty-three.”

“It’s enough. It’s natural. What is the emergency? If a child is seriously ill, it is an emergency. To run in and out of the room because an eighty-three-year-old man may die is not an emergency. It is ugly to behave this way.”

That’s been running around my head: it’s a powerful claim. Obviously it brings to mind the so-called fair-innings argument (FIA) – in essence, the idea that the loss of a young life is for some morally relevant reason worse than the loss of an old one; what counts as the right kind of reason might be the topic for further argument. And irrespective of what one thinks of the FIA in the end, it does have a certain pull. In a situation in which you can save one life and only one life, the idea that one ought to opt for the one that’ll have the best survival time is not without intuitive appeal.

On the other hand, I think that we ought to be wary of expecting it to do too much. Naturally, one is rarely in a situation in which one has to choose between an infant and his great grandfather, and even then, the number of years they’d counterfactually survive is unlikely to be the one thing that separates them. It doesn’t allow us to walk away from the dying octogenarian on the basis that he’s probably on his way out anyway: that interpretation of it would be hyperbolic. We have to be diverting our attention to something with a significant moral import of its own. This might well be someone with a significantly longer life expectancy: I’m not sure whether it’d have to be, since there might be other ways in which we can outweigh the utility from the little extra time we might provide to the elderly – but the general picture is straightforward enough, even if there is fuzziness at the margins. Applied at a more macro level, we might think that it’s more important to spend extra research funding on neonatal medicine than on geriatric medicine on the basis of an appeal to the FIA. But deciding that geriatric medicine is less of a priority wouldn’t mean that we could spend the money on a spectacular Christmas party for the hospital staff.

But more important is the fact that one of the details of the episode as Cavell recounts it is that it’s an emergency. I think that that makes a difference. The FIA offers a way of thinking about questions about who has what kind of claim on our moral attention. It requires that we run some potentially complicated moral algorithms about fairness. But when someone is in immediate danger of dying, I wonder whether those considerations are really all that important. To give them attention may be, to use Bernard Williams’ phrase, to have one thought too many.

Let’s allow for the sake of the argument that 83-year-olds have a diminished entitlement to medical care. Even if we believe that, it wouldn’t follow that medical staff are under any less of an obligation to fight to save them if they’re wheeled into A&E, because that’s simply not how these things work. In a sense, the moral requirements incumbent on medics are not about the patient at all; they’re about the medic. Now, of course, there might be times in which we decide that should a patient face a crisis, we will withhold intensive treatment: that’s what DNR orders are for, and they’re reasonably straightforward. But even they’re things that one decides to impose in cooler moments, and are the exceptions to the rule, so I’m not sure that an appeal to DNRs quite takes the pinch out of emergency situations. Indeed, I’m going to hazard a guess that – at least sometimes – there’s a great temptation to ignore them. (I don’t know. I’ve never been in one.)

The point is that, it’s not crazy to say that, faced with a life that one could save and there are no known constraints like DNRs, advance directives, or whatever, one ought to strive to save it; questions about whether that is a particularly good use of one’s time come some way down the list of priorities. (Very loosely: one ought to try to pull the drowning child from the pond, even if it turns out later that she wanted to be there or at least had no objection.)

My guess is that that was something like what was going on in Cavell père‘s case. Here’s a person in need. Here’s how one responds to a person in need. Job done. Does it make much rational sense? Well, arguendo, let’s say not. But – at risk of labouring the point – is reason a significant factor in emergency cases?

Yes, there might be complicated questions to ask about what one would do when two people need saving and saving both is impossible. The FIA might be mooted as a tie-breaker. But even then, I suspect that it’s too cognitively demanding. Imagine you’re in the process of fighting to save an elderly person, and a teenager is wheeled in with – for the sake of the argument – a condition that is exactly as life-threatening, and exactly as curable if you turn your attention to her now. The FIA might tell us that she wins. I’m not sure. I think that thinking about that might be to have one thought to many. At the very least, it seems perfectly acceptable to me to carry on with the task of saving the person you’d begun to save. It’s bad luck for the teen, for sure; but I’m not sure that there’s an injustice, because it’s not clear whether justice has much currency in emergencies (or, at least, what kind of currency it has).

The other striking thing about Cavell’s anecdote is the appeal to ugliness. I think that that does capture something, but I’m not quite sure what. I’ll have to think about that a bit more…