“There’s an ingrained societal suspicion that intentionally supporting one group hurts another. That equity is a zero sum game. In fact, when the nation targets support where it is needed most—when we create the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully—everyone wins.”

The Curb Cut Effect -Angela Glover Blackwell

I was delighted to be invited to write an article for this blog series as justice and fairness are pivotal values for me, around which everything else stems. I was brought up as a Sikh, which has egalitarianism at its heart. This is exemplified by the fact that when Sikhs are baptised, they give up their “family names” and take on the surname of Kaur or Singh (female and male, respectively) thus eliminating the denotation of hierarchy and class that traditional Sikh family names carry. This is an important statement of personal commitment to equality, humility and service to others. Although I am not baptised, I can’t help but be directed by these values every day. They are in my DNA.

This means I find it hard to witness and accept the injustices built into our health and social care systems, as well as into our wider society (1). In this article, I would like to discuss one such injustice and propose an alternative approach to doing things in healthcare.

Complexity and intersectionality working as exclusion criteria

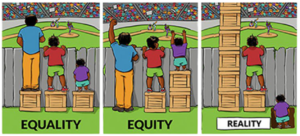

Readers may be familiar with the illustration below (Figure 1), which describes the difference between equality, equity and the current reality (2). Equality is providing the same resources and access to opportunities etc. to all. Equality in an unequal world is however, fundamentally unfair. Equity, as described by WHO is “the absence of unfair, avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically or by other dimensions of inequality” (3). There is another version of the illustration in Figure 1 which includes justice, in which the fence that represents the barriers is completely removed. But writing about the methods to remove the fence is for another blog article!

Figure 1

In my healthcare example, the person in the hole in the ground in this illustration, represents a heterogeneous population with inclusion health needs, and includes: people with a diagnosis of personality disorder, substance misuse or Intellectual Disability; people who are homeless, living in poverty, or facing discrimination; people do not engage the way that professionals want them to engage. But the list goes on and is described in NHSE’s CORE20PLUS5 programme. (4) These heterogeneous factors almost never exist in isolation but cluster together, so that most people in this cohort will suffer from the synergistic effects of intersectionality where two or more disadvantages intersect and become additive(5). Let’s call this cohort “complex” – for want of a better word (though I say this with trepidation as calling this cohort “complex” is one of the ways we let ourselves off the hook from addressing their needs).

This “complex”, intersectional cohort requires more health and social care interventions compared with other cohorts as they have poorer outcomes, and yet they are routinely and systematically excluded from accessing services (6,7). This is not through any malicious or deliberate acts but more I believe, due to a system that is resource-poor, data–hungry and sometimes naïve and driven by wishful thinking. I suggest that the system, in its need for short-term, eye-catching results tells itself that it can address the needs of the “non-complex” majority first. And that it can then circle back to address the needs of this excluded “complex” group in the next phase of whatever project or initiative is being implemented. What happens then of course, is that the health disparities that already existed between the “complex” and “non-complex”, are in-fact widened. Consequently, some methods of combatting healthcare inequalities and improvement are having exactly the opposite effect. All we have done is improved outcomes for the “non-complex” cohort(s), that were already doing better than the ever-excluded “complex” cohort.

I have seen this recurrently in my work on long term conditions like diabetes and chronic kidney disease. In 2018, we mapped mental health services that were available to people with diabetes in NW London, and we demonstrated that services existed for people (8):

- a) with simple depression and anxiety, through what used to be called IAPT (now called Talking Therapies),

- b) with severe and enduring mental illness who are very unwell, through secondary mental health services,

- c) if they happened to meet the criteria for bariatric or eating disorder services, through specialist services in these areas.

However, there were virtually no services for people who had a history of trauma which was impacting their ability to engage with their physical health or with their medical team; or for people who were using drugs or alcohol to try to cope with their distress and trauma (in the home and/or in society as with racism, homophobia etc) (8).

Additional intersectional factors, such as poverty or insecure housing and immigration status, make it more challenging to gain access to health care because of how services are set up (9). How do access services that require you to be registered with a GP if you have been moved five times in a year? How do you arrange, change or cancel appointments if you have no money on your phone or if all your appointment letters are going to the wrong address? Resource-poor services increasingly have stern DNA (did not attend) polices whereby patients get discharged if they DNA once. So already marginalised people are hitting multiple exclusion criteria by multiple services and the system is inadvertently re-traumatising people and confirming their belief that they are alone, and unworthy of help! (7)

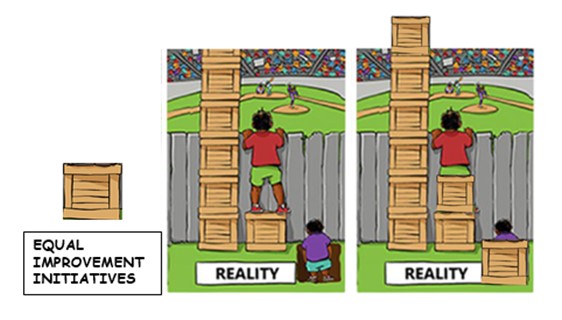

Figure 2

I would like to proffer a modification to the illustration in Figure 1 (see Figure 2) where an additional crate represents “improvement initiatives.” I hope that my modification illustrates that if we create new improvement initiatives that don’t take existing health disparities and barriers to access to services into account, at the very inception phase, then we have essentially done nothing to change the social injustice of healthcare inequalities and instead taken part in the reverse and worsened disparities. Those who were doing ok are still doing ok and those who couldn’t see over the fence still can’t see over the fence. I would go so far as to suggest that the person in the hole in this illustration, is worse off because the crate has them trapped in the hole.

In reality, offering people equal but inequitable access to the newest service improvement, without thinking about or addressing their barriers to access, might be considered to be worse than offering nothing at all. I feel, its tantamount to medical gaslighting which allows us to blame the person (10) instead of looking at the system and its inadequacies. Medical gaslighting also discriminates. It is more likely to happen if the patient is from a minoritised ethnicity, is female, overweight, LGBTQ+, or has long term mental/physical health conditions (10).

Addressing health inequities-starting with the most marginalised cohorts

Even if we don’t come from a place of compassion and desire for justice, doesn’t it make business sense to find better solutions for these marginalised groups of people?

Health Inequalities Impact Assessments and Health Equalities Impact Assessments (HIIAs and HEIAs) have been in use for twenty years (11). These assessments are a way of ensuring that any policy or project implementation is assessed for impact on people with protected characteristics and some explore the impact of social determinants of health. However, I suggest that many simply quantify the risk of disparities at project level but don’t take a social determinants of health (SDH) perspective that is so such a core part of addressing health inequity (1). Many can suffer from inadequate involvement of the most impacted people. My main concern here is that, with notable exceptions, these assessments often start with a policy or project plan that is already somewhere along in the design process, before applying the equity improvement lens. It uses a retrofit approach to equity or equality.

What if we did things the other way around? What if we started our improvement projects with the “complex” cohort? What if we designed a service, WITH them, around THEIR needs and access challenges?

This will seem overwhelming. There are so many inequities and so many intersectional disadvantages that people face. Where do we start? I find it easier to create a person in my mind, who acts as my guiding principle. I call her Grace:

A middle-aged black woman born in Kenya, who has a hypertension, type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. She is overweight, has chronic pain and mobility problems, which she quite often manages using alcohol and prescription opiates. She struggles to afford to pay for food and fuel for two children and her unwell mother. She often fails to attend appointments with professionals because of a combination of these multiple factors, as well as a feeling that her clinicians will tell her off for her lifestyle ‘choices ‘, her poor diabetes and hypertension control and her insidious weight gain.

The questions I ask myself are:

- What if we designed a pathway around Grace by keeping her needs in mind every step of the design process?

- What if we kept her multiple morbidities and her practical access challenges in mind?

- What if we kept in mind her distrust with of services and how this impacts her ability to emotionally engage with her conditions and her professionals?

- What would Grace say if she was listening to our proposed improvement plans?

- How do we ensure she is in the room when we are planning them?

This is an approach that anyone can use. Whether you are considering health equity as an individual professional or as team, department, or sector.

To conclude, for what it is worth, my challenge to us all is this:

- Rather than take a policy or project plan and then filter it through an equity lens,

- We start the design process with equity in mind-we begin with the most “intersection-ally” disadvantaged population and design around them.

It’s an idea that I suggest might help us humanise the people we serve, allow us to see them as people who are surviving despite multiple challenges and bring compassion and empathy into our planning processes.

Perhaps it could even make services better for all if we really thought about access for this cohort. There is an example of this in town planning with The Curb Cut Effect, a term which was introduced to me recently by the inimitable late Dr Onikepe Ijete, SAS psychiatrist and disability campaigner. She talked eloquently about this effect which demonstrates that dropping curbs for wheelchair users was also inadvertently shown to benefit the rest of the population, with one study finding that 9 out of 10 unencumbered pedestrians chose to use the dropped curb (12).

Given this universal benefit why wouldn’t we want to try it out in other spheres? What will be the health equivalent of the curb cut be?

I think we owe it to the people we serve and to ourselves to try to find it.

With thanks and in loving memory of Dr Onikepe Ijete.

References

- Institute of Health Equity. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. 2020. Available from: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/marmot-review-10-years-on/the-marmot-review-10-years-on-executive-summary.pdf [Accessed 28 Jan 2024].

- Interaction Institute for Social Change. Illustrating Equality VS Equity. 2016. Available from: https://interactioninstitute.org/illustrating-equality-vs-equity/ [Accessed 25 Jan 2024].

- World Health Organization. Health Equity. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1 [Accessed 25 Jan 2024].

- NHS England. Core20PLUS5 (adults) – an approach to reducing healthcare inequalities. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/ [Accessed 26 Jan 2024].

- Crenshaw KW. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. U. Chi. Legal F. 139 (1989). Available from: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/3007 [Accessed 28 Jan 2024].

- The King’s Fund. What are health inequalities? (2022) Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/ [Accessed 26 Jan 2024].

- Beale C. Magical thinking and moral injury: exclusion culture in psychiatry. BJPsych Bulletin. 2022.

- Sachar A, Willis T, Basudev N. Mental health in diabetes: can’t afford to address the service gaps or can’t afford not to? Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(690):6-7. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp20X707261. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/70/690/6 [Accessed 25 Jan 2024].

- The King’s Fund. Illustrating the relationship between poverty and NHS services (2024) Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/relationship-poverty-nhs-services (Accessed 20 March 2024)

- Holland M. Medical Gaslighting: Definition, Examples, & How to Handle It. [Internet]. Choosing Therapy. Available from: https://www.choosingtherapy.com/medical-gaslighting/ [Accessed 28 Jan 2024].

- Mahoney M, Morgan RK. Health impact assessment in Australia and New Zealand: an exploration of methodological concerns. 2001.

- Blackwell AG. The Curb-Cut Effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2016;15(1):28–33. DOI: 10.48558/YVMS-CC96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.48558/YVMS-CC96 [Accessed 28 Jan 2024].

Authors

Dr. Amrit Sachar, BM, MRCPsych, MSc

Amrit has worked as a liaison psychiatry consultant in Imperial College Health Care NHS Trust and West London Mental Health Trust since 2005. She is the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Co-Presidential Lead for Equity and Equality working locally and nationally on workforce and patient equity. She is a Health Foundation Generation Q Fellow having completed a Masters in Leadership of Quality Improvement and won RCPsych London Psychiatrist of the Year 2023.

Amrit’s main clinical interests are around integration of mental and social health care into physical health care delivery. She has collaborated with national charities like Diabetes UK and Kidney Care UK, to develop guidance for this in diabetes and renal care. She is particularly interested in addressing the care gaps for people with intersectional protected characteristics, a history of trauma or diagnoses of implicit exclusion, like personality disorder and substance misuse.

She has led delivery of the undergraduate medical education for the trust and Imperial College as well leading clinical services in the trust and delivering transformation across North West London.

Dr. Nagina Khan, BHSc, PGCert, Ph.D.

Nagina is a Senior Clinical Research Fellow in Primary Care, Centre for Health Services Studies (CHSS), Division of Law, Society and Social Justice, School of Social Policy, Sociology & Social Research, University of Kent. She is the CHSS PGR Lead (interim) and Director of the MSc Applied Health Research Programme, University of Kent.

Nagina’s current research supports the Integrated Care Systems (ICS) to capitalise on emerging existing networks in its research duty and mitigate the current risk of future research being conducted in silos and without focus on priorities and underserved populations. This work will diversify the public voice listened to and strengthen ICS strategic links within local research infrastructure to support evidence-based practice, apply solutions, and spread innovation.

Nagina was a senior postdoctoral researcher and Visiting Researcher, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford. She has worked as a Scientist at Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Nagina also worked with Touro University Nevada, Las Vegas, US, and with the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Nagina was a Medical Research Council (MRC) Research Training Fellow, her research was centred on complex interventions for people with depression, University of Manchester. Her post-doctoral studies were undertaken at the NIHR School for Primary Care Research, UK focusing on First episode Psychosis in young people using Early Intervention Services. Nagina’s research interests include Medical Education, Professionalism, Social Justice in Healthcare, Complex Interventions for Depression, First episode Psychosis in Young People, Culturally Appropriate Mental Health Care, Women’s Mental Health, Incentivisation Schemes (P4P) in Healthcare for HICs and LMICs and Global Health. Nagina is the Associate Editor at BMJ Mental Health, she is also the BMJ Leader Editorial Fellow and was an Editorial Board Member of the BioMed Central Medical Education Journal.

Declaration of interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.