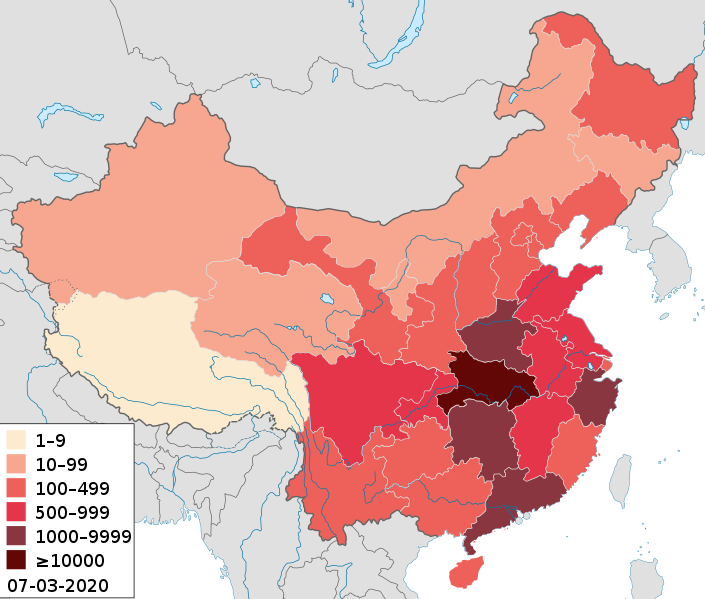

With over a hundred thousand COVID-19 cases across 100 countries , the World Health Organization (WHO), has declared the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (1). COVID-19 originated from Wuhan in the Hubei Province in China, the epicenter of the ongoing coronavirus outbreak since December 2019. COVID-19 is highly contagious and spreads mainly via person-to-person contact and respiratory droplets (2). However, in the past few months, China has been facing a greater challenge—healthcare burnout accompanied by a shortage of trained healthcare workers and medical resources.

It’s been reported that many medical workers in Wuhan see patients without proper protective equipment (3). Apparently they are re-using goggles and gloves and sometimes even using plastic bags and raincoats when medical footwear and protective suits are not in supply (4). Health workers have to refrain from eating, drinking, or using the toilet for hours to make their protective suits last longer (4). By late February, more than 1,700 Chinese medical workers have been infected (4). In China’s effort to contain the outbreak, these healthcare workers have made an immense sacrifice as they work multiple 24-hour shifts, see hundreds of patients a day, and spend very little time with relatives back at home (5). Indeed, China’s medical workers have experienced a tremendous mental and physical exhaustion, as revealed in two Wuhan nurses’ open letter pleading for medics from around the world to help China fight the virus (6).

What has the ongoing outbreak revealed about China’s healthcare system? We must remember that even before COVID-19 , shortage of doctor existed (7). For years, there has been a severe shortage of primary-care physicians in China. A recent study shows that there are just 60,000 licensed general practitioners in a country of 1.4 billion people (8).Till now, the Chinese government has maintained its pricing power over healthcare services and salaries, and as a result, China’s physicians are severely underpaid. According to a 2017 white paper, the average starting salary for a junior physician in China had been $730 a month (9), a figure even lower than the country’s national monthly average of $880 (10). Hence, doctors typically accept “Red Envelops” from patients or pharmaceutical sales for extra earnings (7).

Besides low pay, China’s medical workers have to deal with patient violence. As recent as December 2019, a Chinese doctor was stabbed in the neck by her patient’s relatives and died (11). In a recent survey of general practitioners in Hubei Province, 18.9% of respondents reported being exposed to workplace violence in the preceding year (12). These factors have persuaded many not to pursue a career in medicine. In the past decade the percent of licensed doctors between the age of 25 and 34 has declined by 4%, while those aged 60 or above has increased by 5.2% (13). It’s also found that 45% of the 150,000 Chinese doctors surveyed said they hope their children don’t become doctors (13).

Hence, for China to be better prepared against a crisis like this, it should first mend its healthcare system. New policies should be implemented to raise physician pay rate and protect China’s healthcare workers from retaliations by patients and patients’ relatives. We should also protect these healthcare workers’ wellbeing by offering certified training programs, issuing early warnings against a potential deadly disease, and by making the delivery of donations and medical supplies to hospitals more efficient and transparent.

Lastly, we should remember that we need to protect healthcare workers from burnout. Letting them sacrifice endlessly is not a solution and this is as important as quarantining and treating the infected patients during the outbreak.

About the Author:

Yifei Wang is a medical student at Duke University. She plans to be a doctor who specializes in global public health. She is particularly interested in epidemiological research in infectious diseases, food and drug, the environment, and health policy in China.

Competing Interests:

I have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare no competing interests.

References:

- World Health Organization. Rolling Updates on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How COVID-19 Spreads. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html. 2020.

- The Straits Times. Doctors at China’s Coronavirus Epicenter Wuhan Overworked and Unprotected. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/doctors-at-chinas-coronavirus-epicentre-wuhan-overworked-and-unprotected. 2020.

- The New York Times. China’s Doctors, Fighting the Coronavirus, Beg for Masks. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/14/world/asia/china-coronavirus-doctors.html. 2020.

- South China Morning Post. Meet the Doctors Working Round the Clock to Battle China’s Coronavirus Outbreak. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3047219/meet-doctors-working-round-clock-battle-chinas-coronavirus. 2020.

- The Guardian. Wuhan Nurses’ Plea for International Medics to Help Fight Coronavirus. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/26/wuhan-nurses-plea-international-medics-help-fight-coronavirus. 2020.

- Bloomberg Opinion. China Had a Doctor Crisis Before Coronavirus Hit. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-01-28/china-had-a-doctor-crisis-before-coronavirus-hit-wuhan. 2020.

- The Washington Post. In Wuhan’s Virus Wards, Plenty of Stress by Shortages of Everything Else. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-wuhans-virus-wards-plenty-of-stress-but-shortages-of-everything-else/2020/01/24/ba1c70f0-3ebb-11ea-afe2-090eb37b60b1_story.html. 2020.

- http://www.cmda.net/u/cms/www/201807/06181247ffex.pdf

- Trading Economics. China Average Yearly Wages. https://tradingeconomics.com/china/wages. 2020.

- South China Morning Post. Chinese Doctor’s Murder Overshadows New Law to Improve Public Health Care. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3043842/chinese-doctors-murder-overshadows-new-law-improve-public. 2019.

- Gan et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Workplace Violence Against General Practitioners in Hubei, China. 2018; 108(9): 1223-1226.

- Sixth Tone. Why China’s Young Doctors Want Out of the System. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1003446/why-chinas-young-doctors-want-out-of-the-system. 2019.