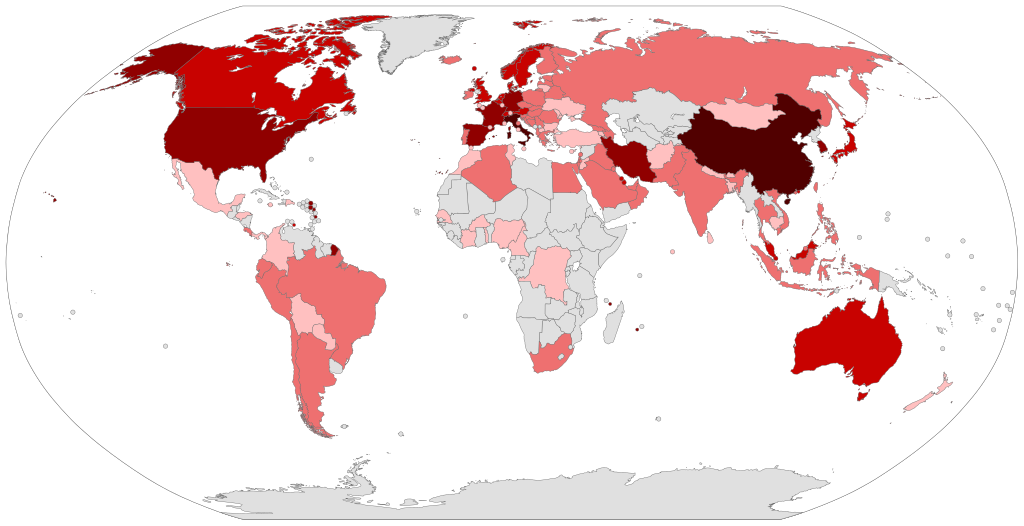

Following the second meeting of the Emergency Committee convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General, the novel Corona virus or COVID-19 outbreak was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). This has negatively impacted the global economy and global travel, with growing concerns for preparedness of health systems worldwide and its impact on health outcomes. This commentary shines a light on the health workforce who are the first responders and often the victims of weak health systems.

Health workers – the first line of defence against epidemics.

Primary care doctors have a crucial role to play in protecting the community as COVID-19 spreads through countries. With proper support which includes adequate information about viral outbreaks, standardised protocols/guidelines and personal protective equipment, health workers can help raise the alarm to contain, and interrupt community transmission of diseases. In Wuhan, Dr Li Wenliang, was among the first health workers to notice patients with SARS like symptoms and raise the alarm. Unfortunately, his concerns were challenged by the authorities which delayed the early period of containment of the virus. Hence, health worker empowerment is a vital part of pandemic preparedness. The New South Wales Influenza Pandemic Plan mentions this as part of its objectives – informing, engaging and empowering the public and health professionals in their response to epidemics, minimising the burden on the health system, and ensuring all health sectors work in partnership. Since health worker empowerment is an important part of pandemic preparedness, there have been concerns for countries with weak health systems. For example, during the Ebola outbreak, inadequate numbers of health workers and poor health information systems were crucial factors that hampered timely response in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Health workers – the most vulnerable in epidemics

Unfortunately in some cases, the health workforce lacks this support and are often the first victims of the outbreak, inevitably increasing the population’s risk of contagion. For China where the outbreak started, up to 1,716 health workers got the infection either from a member of their household, or from the hospital during the early phase of the outbreak when infection control measures were not yet in place, and six health workers died as a result of the infection (as of 17th February, 2020).

Iran, which was known to have a robust health system with an effective referral pathway between primary, secondary and tertiary care is facing it’s on battle with shortages of health professionals. Reports from the country highlight the lack of access to medicines and personal protective equipment which has led to health workers ‘wrapping themselves in table cloths to protect themselves’.

Despite having a strong health system with sufficient skilled health professionals in South Korea, the country’s health workforce is struggling with the rate of spread of the infection. Lombardy in Italy has seen the largest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Europe. Shortage of trained staff is also a problem here, and the current medical staff account for up to 12% of those who infected.

In Australia there have been concerns that GPs still do not have enough personal protective equipment, though the government has now secured PPE and is rolling out a plan to establish pop-up clinics across the country and include tele-health as a Medicare reimbursable item to contain the spread of the virus.

Once the COVID-19 is contained and life goes back to normal for countries, the health workforce will need to be supported through their physical stress and mental exhaustion.

Beyond the workforce – health system readiness

It appears every country (high- and low-income countries inclusive) has a gap in its pandemic preparedness. The Global Health Security (GHS) Index, a comprehensive assessment of global health security capabilities in 195 countries, is 40.2, with many middle- and high-income countries scoring below 50%. According to the GHS Index assessment, most countries lack the essential health system capacity for pandemic response, only about 27% of countries have demonstrated the existence of an updated health workforce strategy, 3% have prioritized healthcare services for health workers who fall ill during a public health emergency response, and skilled health worker density is a concern globally.

In a recent commentary in NEJM, Bill Gates highlighted the importance of strengthening primary health care systems in low- and middle-income countries as that forms the basic infrastructure to fight epidemics and prevent premature mortality. Trained health care workers not only provide ante-natal care and deliver vaccines; they also monitor disease trends and serve an important part of the early warning systems to potential epidemics.

Even though many low- and middle-income countries have weak health systems and a deficient health workforce, weak links for pandemic preparedness also exists in high-income countries. There is thus a need for collective responsibility in holding relevant actors in high-and-low income countries accountable to promoting public health and supporting an optimal health workforce. This can be achieved by answering the call to reciprocity and true humility. There are benefits when high-and-low income countries participate in authentic global health partnerships.

So, where to from here?

COVID-19 outbreak is another opportunity to build on the lessons from The Ebola outbreak, i.e. a collective response from the global community is needed to ensure health system resilience during and after epidemics. International Health Regulations are needed to keep all countries accountable to building core public health capacities and coordinating a response to health emergencies, and lastly, there is a need for a strong and committed global health workforce, that is empowered and supported while serving at the coal face of infectious and chronic diseases. Five decades from today, let us not look back at the missed opportunities, lets take this moment in history to drive change, train, retain, and sustain our health workforce – the most important and vulnerable part of our health systems

About the authors

Kenneth Yakubu is a family physician with experience in patient, family and community-oriented health care. He is studying for a PhD in Global Health at the University of New South Wales and The George Institute for Global Health. His current research seeks to explore challenges and solutions for achieving a sustainable global health workforce.

Kenneth Yakubu is a family physician with experience in patient, family and community-oriented health care. He is studying for a PhD in Global Health at the University of New South Wales and The George Institute for Global Health. His current research seeks to explore challenges and solutions for achieving a sustainable global health workforce.

Rohina Joshi is the Head of the Global Health Workforce Program in the Centre for Health Systems Science of The George Institute for Global Health. She is also an Associate Professor and Scientia Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney; an Honorary Associate Professor, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney; and Senior Manager at the George Institute India. Her research focus includes the use of data to promote health and prevent disease, as well as discovering novel approaches for supporting frontline health workforce.

Rohina Joshi is the Head of the Global Health Workforce Program in the Centre for Health Systems Science of The George Institute for Global Health. She is also an Associate Professor and Scientia Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney; an Honorary Associate Professor, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney; and Senior Manager at the George Institute India. Her research focus includes the use of data to promote health and prevent disease, as well as discovering novel approaches for supporting frontline health workforce.

Competing interests:

We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no relevant conflicts of interests to declare.