During the recent debate about the use of the word “curry”, I looked it up in Hobson–Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive, also described variously in reissues as The definitive glossary of British India, The Anglo-Indian Dictionary, and A spice-box of etymological curiosities and colourful expressions. The last is particularly apt.

Hobson–Jobson was written and compiled by Henry Yule and A[rthur] C[oke] Burnell, published in 1886, and updated in 1903 by William Crooke. In their introductory remarks they wrote that “In its original conception [the dictionary] was intended to deal with all that class of words which, not in general pertaining to the technicalities of administration, recur constantly in the daily intercourse of the English in India, either as expressing ideas really not provided for by our mother tongue, or supposed by the speakers (often quite erroneously) to express something not capable of just denotation by any English term.” However, we later learn that “as the work proceeded, its scope expanded somewhat, and its authors found it expedient to introduce and trace many words of Asiatic origin which have disappeared from colloquial use, or perhaps never entered it, but which occur in old writers on the East.”

As James Lambert’s comprehensive analysis in 2018 shows, Hobson–Jobson is a highly idiosyncratic dictionary. At first sight the format appears to be standard—2400 or so headwords arranged alphabetically. But Hobson–Jobson is not a conventional dictionary.

Headwords Among the headwords, spelt inconsistently, are single words and phrases; some are variant spellings with cross-references, but variants are not included in the main entries, although many can be found in the quotations that illustrate the uses of the headwords.

Parts of speech Most of the headwords, although not all, are followed by an abbreviation indicating the part of speech: s. (substantive, i.e. a noun) and n.p. (nomen proprium, i.e. a proper noun) make up about 97% of all the entries. The rest are mostly adjectives, with occasional verbs and interjections. You will have difficulty finding any other parts of speech.

Pronunciation is rarely indicated.

Etymologies Some of the entries, although not all, include etymologies, but they are peculiarly organized. In some cases the language of origin is given (e.g. Hindi, Malayalam, Tamil, Arabic, Chinese, Sanskrit), but often not. Etymologies are often discussed after the meaning is mentioned and in some cases the discussion concentrates more on supposed, but incorrect, origins, the true etymology being mentioned only briefly, almost as an afterthought.

Definitions Most of the headwords are described in simple definitions, but some are described discursively and some not at all. But after all, the authors did call their work “discursive”.

Quotations Many of the entries are followed by selections of quotations, intended to illustrate the meanings and uses of the term. However, the number of quotations varies widely from headword to headword and they are of hugely variable length and inconsistently chosen. Unlike the New English Dictionary, to which the dictionary occasionally refers, there is no attempt at a historical approach, identifying the earliest use of a term and its development.

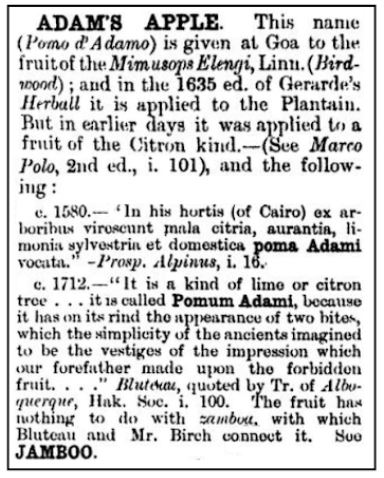

The entry for Adam’s apple illustrates some of these points.

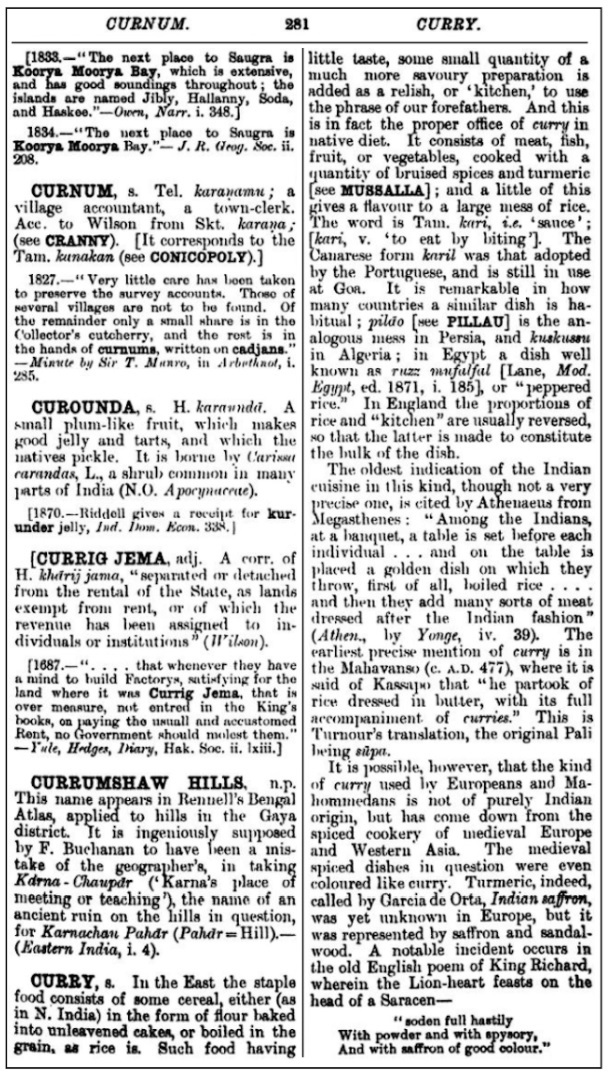

So what about “curry”? The entry in Hobson–Jobson runs to nearly four columns and includes the etymology, from the Tamil word kari, sauce or relish for rice, and the Kannada word karil, which gives the modern Portuguese word caril.

The current objection to our use of “curry”, if I have understood it correctly, is that the word is not used in India to describe the many spiced regional dishes eaten there. Rather, each dish has its own individual name. Therefore, so the argument goes, the word “curry”, referring to any spiced dish, should be abandoned. This misunderstands the ways in which language develops and the ways in which words are used. For all its faults, Hobson–Jobson illustrates this well, listing as it does words from many different languages, imported into the English spoken in India, and used in ways that were not intended in the languages from which they originally came. Languages constantly borrow words, “loan-words” or “calques”, from other languages and develop them. What other words will we next be called on to abandon?

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: none declared.