A collaboration between the Point of Care Foundation in the UK and members of the international Vermont Oxford Network of specialist neonatal care centres have been using experience based co-design to drive quality improvement. In this article, staff and family team members at the Portland Providence Hospital in Oregon describe how they have worked together and the changes this has brought about.

Howard Cohen, neonatologist

Long experience as a neonatologist has made me very aware of the importance of supporting families whose infants are being cared for in neonatal intensive care units, and how working with them can help improve the quality of care. I was therefore delighted to be invited to play a leading role in a joint initiative started in 2019 between the Point of Care Foundation in the UK and the Vermont Oxford Network (VON). Founded in 1988, VON is a nonprofit global collaboration of healthcare professionals and families representing Children’s Hospitals, neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and birthing hospitals with a shared mission to improve neonatal care.

Long experience as a neonatologist has made me very aware of the importance of supporting families whose infants are being cared for in neonatal intensive care units, and how working with them can help improve the quality of care. I was therefore delighted to be invited to play a leading role in a joint initiative started in 2019 between the Point of Care Foundation in the UK and the Vermont Oxford Network (VON). Founded in 1988, VON is a nonprofit global collaboration of healthcare professionals and families representing Children’s Hospitals, neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and birthing hospitals with a shared mission to improve neonatal care.

VON’s collaborative partnership with the Point of Care Foundation is a programme to introduce, support, and embed Experience Based Co-Design (EBCD)1 to drive quality improvement. This methodology is well established and has been shown to empower patients and give them a sense of community.2,3

Support for EBCD was offered to centres enrolled and participating in our internet based quality collaborative work focused on critical transitions of care, particularly admission to and discharge from intensive care. Of the sixty-five centers enrolled, twelve felt ready to learn and include EBCD in their quality improvement work. One of the centres, the Providence Portland Medical Center in Oregon, is a 19 bed NICU that serves the metropolitan area as well as babies and families transferred from other maternity hospitals outside of Portland.

Marybeth Fry, “Veteran” neonatal intensive care parent and co-lead of the Portland initiative

Offering families the opportunity to reflect upon their experience of having an infant on a neonatal care unit and providing critical feedback on how it affected them is healing for families, and central to helping improve care. Hearing from staff about the areas where they believe improvement is needed is equally important. Both provide opportunities for ownership of improvements and when the two groups are brought together our experience suggests the impacts are positive and long lasting.

Offering families the opportunity to reflect upon their experience of having an infant on a neonatal care unit and providing critical feedback on how it affected them is healing for families, and central to helping improve care. Hearing from staff about the areas where they believe improvement is needed is equally important. Both provide opportunities for ownership of improvements and when the two groups are brought together our experience suggests the impacts are positive and long lasting.

Sarah Pearce, neonatologist and associate medical director of the Portland Medical Centre

When VON approached our team to be the pilot site for a transformative approach to quality improvement that involved working as partners with families, our team was delighted. It gave us the structure we needed to engage families whose infants had been on our unit and we started with interviewing 13 staff members and 10 families, and followed this up with three focused feedback events. We chose to go to families whose experience of care was six months to three years since their child was discharged from the unit. Initially we created an interview guide, but quickly learned that allowing families to tell their stories their own way worked best.

When VON approached our team to be the pilot site for a transformative approach to quality improvement that involved working as partners with families, our team was delighted. It gave us the structure we needed to engage families whose infants had been on our unit and we started with interviewing 13 staff members and 10 families, and followed this up with three focused feedback events. We chose to go to families whose experience of care was six months to three years since their child was discharged from the unit. Initially we created an interview guide, but quickly learned that allowing families to tell their stories their own way worked best.

For staff interviews, the plan was to recruit them at unit meetings and via our electronic weekly newsletter. Our staff surprised us, for initially they were reluctant to go on camera and provide formal feedback. We therefore went on to provide a more detailed explanation of our goals, the process, and distributed the interview guide, and these measures boosted participation.

The key themes which emerged from interviews with patients and staff showed appreciable overlap and were broadly grouped under the need for improvements to the environment, better communication, and more family support. The need for more consistency in care was also identified by families. Areas for improvement were discussed at separate staff and family focused feedback events and then at a joint event. Our co-design team (made up of families and staff interviewees) then used the information to create a diagram to help focus our units work on improving family involvement in care and discharge home processes.

Jessica Mozeico, parent

I am the mother of a child who was in the neonatal unit of Providence Portland for four weeks. I had been diagnosed with unexplained infertility, but found myself pregnant for the first time at age 42, so I considered my pregnancy a miracle. After 32 weeks of a healthy pregnancy, I went into preterm labor and was petrified to find my tiny daughter and myself in the NICU. I was worried that my daughter would not make it out of the hospital or that she would be developmentally impacted in ways I couldn’t imagine.

I am the mother of a child who was in the neonatal unit of Providence Portland for four weeks. I had been diagnosed with unexplained infertility, but found myself pregnant for the first time at age 42, so I considered my pregnancy a miracle. After 32 weeks of a healthy pregnancy, I went into preterm labor and was petrified to find my tiny daughter and myself in the NICU. I was worried that my daughter would not make it out of the hospital or that she would be developmentally impacted in ways I couldn’t imagine.

Three years after this experience, I was contacted by a NICU nurse and asked if I would agree to provide a patient caregiver perspective of our NICU experience. We were told that this would involve an interview lasting an hour, which would be video recorded and that this interview together with those obtained from other parents would be used to pull out individual and common topics/themes expressed by families that would later be discussed in in group workshops, first among families alone and later with families and caregivers together, to identify issues where it was clear that action needed to be taken to improve the quality of care.

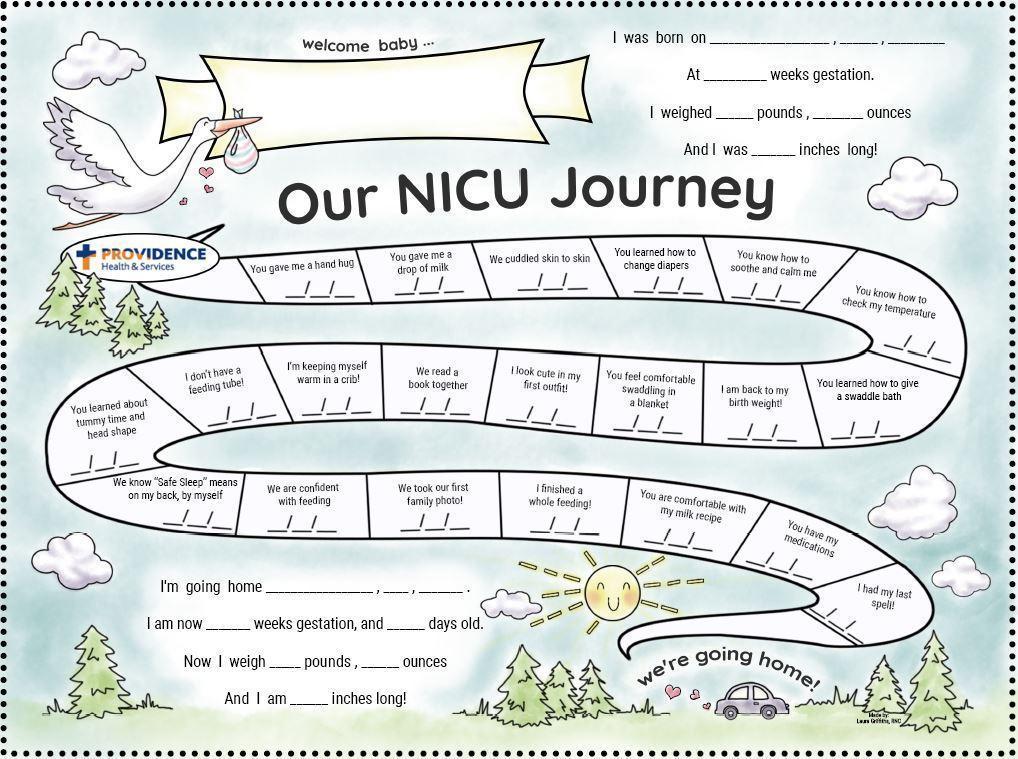

Being involved in a joint initiative to assess the experience of families and staff was empowering and it was heartening to find that all families’ experiences, and points of pain and distress, were valued, no matter how trivial they may have seemed. For example, the families discussed how confusing it felt to try and understand the milestones that our babies needed to pass in order to be discharged home and how intimidating it was when we were told we could go home imminently. Our concern about when, why, and how decisions were made about discharging infants from the neonatal unit led to a process change, in which NICU families were given a chart after admission that would outline the milestones that a baby must pass before they were judged to be well enough to leave the unit. The group also identified a checklist of activities of daily living that a family must demonstrate in order to feel more confident before discharge. Had this been in place when we were being discharged, I would have been more secure that I could demonstrate the care tasks for my baby when I went home.

What stands out to me after being involved in this process is that the gaps between current routine care and optimal care are often not identified by either healthcare professionals or families alone, but that they come to light when we jointly discuss our experience. For example, families identified how emotionally fraught we were to leave our infants to eat our meals and the challenge this placed on breastfeeding mothers. We were not able to articulate a solution to this, but after discussing this concern with the health care professionals, we jointly created the solution of meals being available on the unit so families would not need to leave their infants. I am extremely grateful for the opportunity to be involved in a quality improvement project and hope that our experience in neonatal care will encourage other departments in this hospital and in other hospitals to adopt experience based co design in their quality improvement initiatives.

Julie Metcalf, neonatal nurse practitioner

Our multi-disciplinary, co-design team (a neonatologist, neonatal nurse practitioner, bedside nurses, developmental therapists, and former neonatal ICU families) used the information from interviews to create a change driver diagram (see illustration) to improve the family experience and the discharge process. As changes were implemented, we had to develop a new level of comfort with improvements that were impactful, but not necessarily measurable such as food for families rooming in and white boards to communicate information in patient rooms. Over the last two years our co-design team has implemented the following improvements:

Our multi-disciplinary, co-design team (a neonatologist, neonatal nurse practitioner, bedside nurses, developmental therapists, and former neonatal ICU families) used the information from interviews to create a change driver diagram (see illustration) to improve the family experience and the discharge process. As changes were implemented, we had to develop a new level of comfort with improvements that were impactful, but not necessarily measurable such as food for families rooming in and white boards to communicate information in patient rooms. Over the last two years our co-design team has implemented the following improvements:

(a) Installation of whiteboards in individual patient rooms to promote improved communication and facilitate discharge planning.

(b) Creation of a virtual discharge tour of our Developmental Follow-up Clinic to enhance understanding of the transition from inpatient developmental care to outpatient developmental follow-up.

(c) Establishing a Patient & Family Advisory Committee to support the unit and families

(d) Creation of Family Binders which include a “Road Map to Home,” daily journal pages, a glossary of terms, a section devoted to discharge preparation, and a survey for families to evaluate their readiness for the transition to home.

(e) We worked with infection prevention and hospital management staff to allow families to have food in the patient rooms.

How the unit responded to the covid-19 pandemic

During the acute stage of the pandemic, the highest level neonatal intensive care unit was closed to make room for adult covid overflow beds. Staffing levels were affected and infants transferred to a “sister” unit. A second level 6-bed open bay nursery was opened which due to spatial constraints did not allow for more than one family member at the bedside at a time. Despite these challenges our team remained devoted to improving the care of infants and families.

Infants who are born preterm or who have had neurologic injury related to their birth are at increased risk for a range of motor, behavioral, cognitive, sensory, and linguistic problems.5 Close follow-up of infants deemed to be at high risk of problems is necessary for early detection, timely intervention, and promotion of better health outcomes in the vulnerable NICU graduate population.4,6 To maintain close surveillance of at-risk infants our team moved what had formerly been an in-person tour of the adjacent developmental clinic into a virtual tour that was included in the discharge preparation for families whose infants met the criteria for developmental follow-up.

The video was created using information from the interviews with families and the co-design working group. Preliminary data comparing follow-up rates prior and post the implementation of the video virtual tour showed significant improvement in attendance at the first developmental appointment, from 55-59% to 91%.

Lessons learned:

- Adopting the EBCD-method of quality improvement reduces hierarchical barriers between staff and families.

- Families and staff value the opportunity to provide critical feedback about their experience, be actively involved in improvements in care, and take ownership of them.

- Bringing the two groups together is a powerful way of achieving effective and lasting change.

Competing interests: Howard Cohen and Marybeth Fry are both faculty for the Vermont Oxford Network for which we are paid. No further COIs declared.

References

- Point of Care Foundation. (2016). Experienced-based co-design toolkit. Retrieved from: https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/experience7-based-co-design-ebcd-toolkit/

- Coy, K., Brock, P., Pomeroy, J., Cadogan, J., & Beckett, K. (2019). A road less travelled: Using experience-based co-design to map children’s and families’ emotional journey following burn injury and identify service improvements. Burns, 7, 24. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2019.07.024

- Gustavsson, S. (2013). Improvements in neonatal care: Using experience-based co-design. International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance, 27(5), 427-438. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-01-2013-0016

- Bockli, K., Andrews, B., Pellerite, M., & Meadow, W. (2014). Trends and challenges in United States neonatal intensive care unit’s follow-up clinics. Journal of Perinatology, 34, 71-74. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.136

- Novack, I., & Morgan, C. (2019). High-risk follow-up: Early intervention and rehabilitation. In L.S. de Vries & H.C. Glass (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64029-1.00023-0

- Goldstein, R.F., & Malcolm, W.F. (2018). Care of the neonatal intensive care unit graduate after discharge. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 66, 489-508. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.12.014