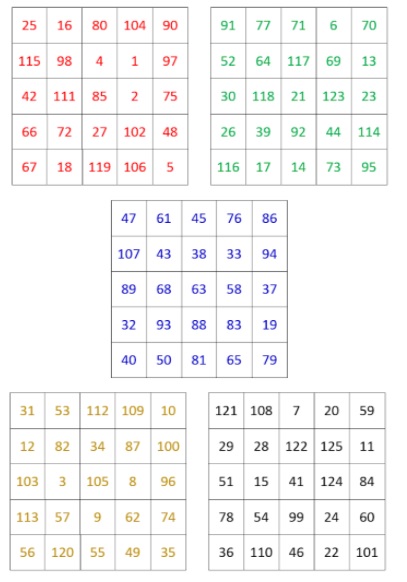

The earliest citation of the term “off-label” in the Oxford English Dictionary is from 1987 (Table 1). But I looked for other instances, suspecting earlier uses.

Table 1. Biomedical words (n=19) in the OED for which the earliest citations are from 1987 (out of a total of 157); I have found two antedatings

*Antedatings: non-nucleoside (1965); off-label—see text

The dictionary deals very thoroughly with the several different meanings of “label”. It classifies them under three main headings:

I. A narrow band or strip.

II. A supplementary note appended to a text.

III. A piece of paper, etc., which provides information about something to which it is appended, and related senses.

The first definition under the last of these, glossed as “Now the usual sense”, is “A piece of paper, cardboard, metal, or other material, attached or intended to be attached to something in order to provide information about it; (hence) the information, or a piece of information, on the packaging of a product.” But this doesn’t quite capture the modern sense of the word when used in relation to licensed medicines.

In 1906 the US novelist Upton Sinclair published a book called The Jungle, in which he described the plight of poor European immigrants, whose work with meat products in the Chicago stockyards was “stupefying [and] brutalizing”. The subsequent public outcry led the US Congress to promulgate the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which mandated labelling of foods and medicinal products. The Bureau of Chemistry that was established by the 1906 Act became the Food and Drug Administration in 1930.

Following various amendments to the 1906 Act, a new Act was promulgated in 1938, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, in which a label was defined as “a display of written, printed, or graphic matter upon the immediate container of any article”, with the added requirement “that any word, statement, or other information appear[ing] on the label shall not be considered to be complied with unless such word, statement, or other information also appears on the outside container or wrapper, if any there be, of the retail package of such article, or is easily legible through the outside container or wrapper.” Labelling was defined as “all labels and other written, printed, or graphic matter (1) upon any article or any of its containers or wrappers, or (2) accompanying such article.”

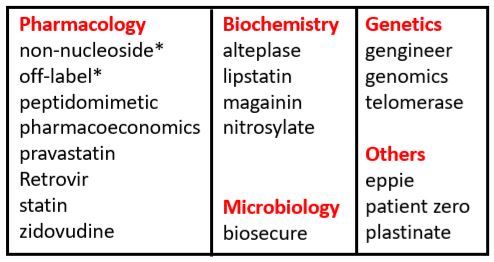

In the light of the last three words in this definition, the term “off-label” was then used to refer to information about a product that was to be found, not on the label on the packaging, but in some other written source, such as a brochure or advertisement; two examples, from 1965 and 1980, are shown in Figure 1. These earlier references to “off-label” (and there may be earlier examples to be found) relate to the first meaning of the term defined in the OED: “Relating to or designating the use of a substance, esp. a drug, for a purpose or in a circumstance other than those for which it is officially approved”.

Figure 1. Two instances of “off-label”; the first, relating to prescription drugs, is from a discussion in the US Congress in 1963 (reported in 1965) of the proposed Packaging and Labeling Controls Act; the second, relating to foodstuffs, is from a statement by US Senator George McGovern given before the Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research of the Committee on Labor and Human Resources on 19 March 1980.

However, the term “label” is now also used to mean not merely the written, printed, or graphic matter that accompanies a formulation, but also the informative content of such matter, which in the UK is contained in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC), previously called the Product Data Sheet. The SmPC is a legal document, approved as part of the marketing authorization (licensing) of each medicine, and its contents are prescribed by law. The term “label” in this context comes from a shortening of the original term “labeling”, as defined in a 1972 FDA statement about a proposed regulation: “The labeling of a drug … presents a full disclosure summarization of the drug use information which the supplier of the drug is required to develop from accumulated clinical experience and systematic drug trials”.

The difference between “label” and “labeling” was also pointed out at a meeting of the 73rd Congress in 1935 by Walter G Campbell, the third US Commissioner of Food and Drugs: “At the present time the law has control over those statements that are attached to or that accompany the package in the form of circulars. For purposes of the subsequent requirements of this bill these have been divided into two classes; first, ‘label’ meaning the principal label or labels upon the immediate container of any food, drug, or cosmetic, and upon the outside container or wrapper, if any there be, of the retail package of any food, drug, or cosmetic. Then the term ‘labeling’ is defined so as to include not only the label but all circulars and material and placards for display purposes and the like that may in any form whatever accompany the article of food, drug, or cosmetic.”

[“labelling” here is correctly spelt with one l, the American spelling.]

Thus, the OED gives a second definition of “off-label”, dating its first use from 1990: “Of the use of a substance, esp. a drug, for a purpose or in a circumstance other than those for which it is officially approved”. “Intervention” might replace “substance” in this definition, to encompass devices. And “medicine”, implying a medicinal product, might replace “drug”.

The opposite term, “on-label”, which can be found as early as 1998 in relation to the therapeutic use of ultrasound, although not yet included in the OED, is easily defined, as the use of an intervention, especially a medicine, in accordance with its licensed indications.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

|

This week’s interesting integer: 315 Named numbers

Sums of 315

157 + 158

103 + 105 + 107

12 + 52 + 172 32 + 92 + 152 52 + 112 + 132 Pythagorean triangles

Geometric numbers

Magic cubes

|