Trish Greenhalgh and Graham Mackenzie

Covid-19 has put the science of rapid review centre stage. It is only just over six months ago that the world began to grapple with an entirely new disease whose natural history, prevention, treatment and wider management were completely unknown. Since then, tens of thousands of scientific papers and preprints have been published, and a new industry has emerged to summarise and synthesise these primary studies as quickly as possible.

In parallel, covid-19 also became the story in the lay press. Hardly anyone was untouched by its medical, social, and economic fallout. Narratives and counter-narratives emerged and circulated in both the mainstream and social media. Allegations of “fake news” were frequent, and fact-checking services put in overtime. While the ratio of sense to nonsense in these sources was often weak, they were nevertheless a potential source of testable hypotheses about where covid-19 had come from and how it might be brought under control.

In this context, we used Twitter analytics to inform a rapid review of scientific evidence on the link between meat and poultry facilities and covid-19 clusters.

In these virus-focused times it seems ironic to be writing about the opposite of a viral tweet. The act of sharing information on Twitter is frequently unnoticed, with a substantial proportion of tweets never shared or acknowledged. The effort might be not wasted, however, if tweets can be harnessed to understand the public perspective on a topical issue.

We used this idea to explore how covid-19 outbreaks were affecting the meatpacking industry. We were looking at the topic for a review of conditions in meat processing plants. We took a public health approach, looking at the whole system, from farm-to-fork, from the pressured meatpacker performing grinding and poorly remunerated work to the meat magnates, and across the political spectrum.

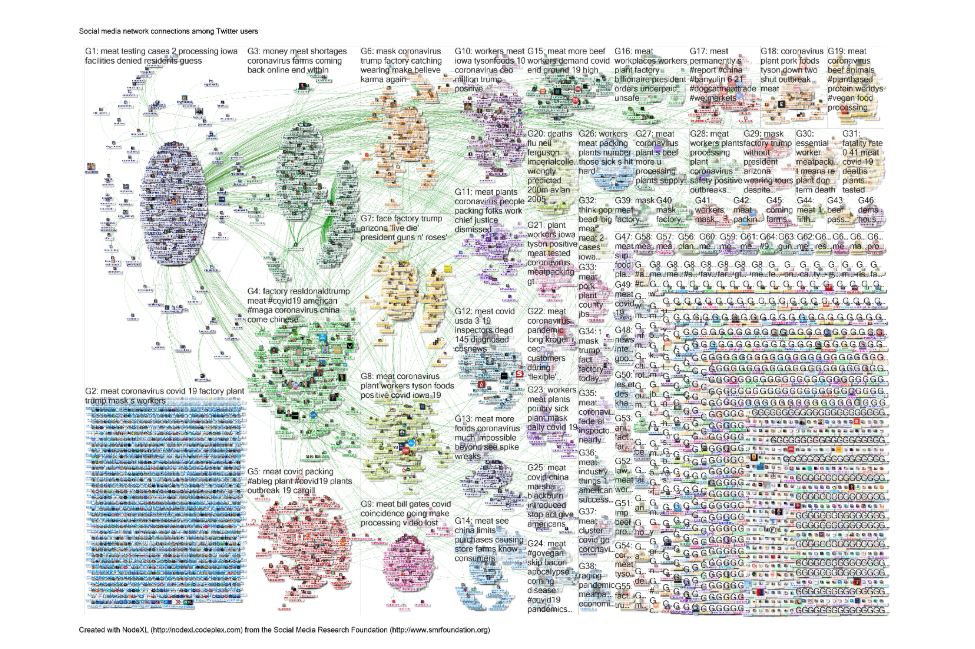

There were tens of thousands of tweets on this topic during April and May 2020. However, challenges in the scale of the task provided an unexpected solution. NodeXL identifies clusters of tweeters, grouped together by shared interests, followers and other tweeting patterns, with frequently polarised views between clusters. It also provides a list of top weblinks (URLs) – the very news stories, blogs and videos that we were interested in capturing– for each of the 10 most prominent clusters of tweeters in each search, giving up to 100 URLs per report. The methods and list of top URLs identified are listed in a Wakelet summary.

The topics identified from these news stories and blogs demonstrate the complex public health problems faced by meatpackers, both before and during the covid-19 pandemic. Donald Trump recently classified meatpackers as “essential workers”, forcing meat plants to stay open to secure supply chains. However, meatpackers are working in conditions that, like nursing homes and hospital wards, make them highly susceptible to catching and spreading covid-19 unless they have adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing. Our search found personal testimony and local journalism covering the human side of the story, with a spread of stories across the US meatpacking states and beyond.

Families of workers who died of covid-19 revealed concerns about conditions, including availability and use of PPE. Many meatpackers are from vulnerable groups, including asylum seekers and refugees, with limited English to understand safety information. Covid-19 outbreaks in meat processing plants have wider impacts—on families, and a correlation with nursing home outbreaks in these areas. Cases and deaths were reported in meat industry inspectors in the US and Canada, some of whom replaced ill colleagues, with only basic training. Video footage from meat processing plants and tracking of meat products crisscrossing the US reveal further challenges in controlling the pandemic. Right-wing politicians cast doubts about home circumstances of meatpackers, in an ugly echo of Michael Marmot’s concept of “lifestyle drift”: don’t blame the systems that cause the problems, focus on—and blame—the individuals.

Our work shows how a systematic search of tweets can capture a wide range of evidence and opinion (of varying kinds), which we can analyse systematically for testable hypotheses. The range of sources identified through this approach was much broader than a Google search over the same period.

In his 1906 novel “The Jungle” Upton Sinclair wrote about the American meat industry: “It was all so very businesslike that one watched it fascinated. It was pork-making by machinery, pork-making by applied mathematics”. Conditions improved after his exposé, until upheaval in the meat industry in the 1970s, sowing the seeds of current problems. The “applied mathematics” of analysing social media big data can help us capture contemporary stories about the meat industry, and catalyse the public health change required to protect vulnerable workers and the wider public.

Our Twitter analytics data has fed into an ongoing rapid review which will be published on the Oxford Covid-19 Evidence website shortly.

Graham Mackenzie, GPST2, NHS Education for Scotland. Twitter: @gmacscotland Graham Mackenzie has been a doctor for almost 25 years, and is currently retraining as a GP. He has also worked in hospital medicine and was a Consultant in Public Health Medicine in NHS Lothian for 11 years, during which time his remit included women and children’s health and quality improvement.

Trish Greenhalgh, Professor of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. Twitter: @trishgreenhalgh Trish Greenhalgh is an academic GP and Professor of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford. She is active on Twitter and has published on howjudicious use of social media can help academic research and service improvement.