Imagine that you are driving a taxi which cannot stop, except in dire emergencies. Every ten minutes, you must take it to a new destination. If you take too long, your waiting fares will get fed up and you will get bad marks. Still worse if you have an accident or take them to the wrong place. So what’s the best plan?

- Memorize every possible route and destination

- Keep a heap of maps on your passenger seat

- Just hope for the best and navigate by familiar landmarks and road signs

- Get satnav

I’m talking about general practice here. London cabbies used to have to do “the knowledge” across the whole of the city, just as GPs still stuff their brains with lots of “just in case” knowledge about the whole of medicine. But how much safer I’d feel, as a passenger, if they had satnav as well.

When computers became a mandatory part of NHS general practice 25 years ago, GPs were made to feed the machine with lots of data. But we got little in return. In those early days, there was nothing to guide the doctor towards reaching the destination that the patient wanted to get to. Later, our dashboards began to fill up with destinations that the patient didn’t necessarily want to get to—having their BP checked, being told to get weighed, having a medication review or a flu jab. And there was a growing profusion of maps on the passenger seat, sometimes contradicting each other, available as paper booklets from NICE, or on websites that took valuable minutes to negotiate while you took your eyes off the road.

Meanwhile every cabbie and Uber driver went over to satnav. They got updated information about every route and every hold-up in real time. They could look and drive at the same time. They got to the right place by the quickest route.

So what’s the current situation in general practice? There’s still no satnav to guide most decisions about treatment. But enormous efforts have been made over the last few years to get GPs to prescribe more statins to the right patients and fewer to those who don’t need them. A NICE guideline appeared in 2014 which stretched to nearly 400 pages and contained over 90 recommendations about how to arrive at a decision with each adult in the UK. This was subsequently distilled into a 23 page shared decision aid for use mainly by GPs.

It is but one of many. Statins are the best-researched of all drug groups, and certainly the most widely discussed. You can’t give a talk about evidence-based medicine or shared decision making without someone starting a discussion about them which generally takes over the whole meeting.

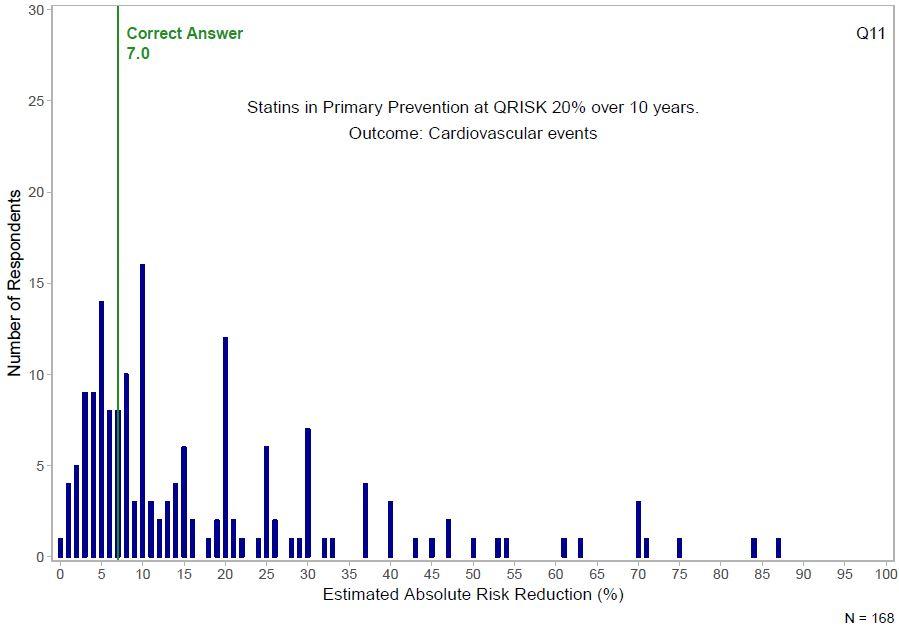

An article has just appeared in BJGP Open which examines the effect of this intensive knowledge dissemination among GPs. It includes a figure showing how they fare with statins used for primary prevention.

In one sense this might seem quite reassuring. It could demonstrate that GPs are concentrating their minds on helping people who are ill or needy, rather on tasks which are better done by healthy people using electronic decision aids. On the other hand, it could mean that GPs are equally bad at understanding the true benefits and harms of a lot of other interventions. And unfortunately this is confirmed by the rest of the study, covering a total of 20 clinical scenarios presented to two large groups of GPs. For all questions combined, 87.7% of responders overestimated and 8.9% underestimated treatment effects. However, specialists fare little better, according to a systematic review of 48 studies over a range of specialties.

All doctors could do with some proper satnav. It doesn’t even have to be that good. Never mind the confidence intervals, we can deal with those when we get closer: just tell us whether we’re in Camberwell or Crawley while we talk to our patients.

I’m well aware that lots of excellent people have been trying to do this over the last two decades. Since retiring from general practice 10 years ago, I’ve even tried to act as a sort of dating agency to put them in touch with each other. But this job shouldn’t fall to groups of highly motivated individuals producing a patchy ecosystem of different tools and apps on shoestring budgets. Getting reliable information to patients and clinicians for decision making in real time should be a top priority for all health systems across the world. If cabbies and other drivers can have satnav, so should patients and health professionals.

Richard Lehman is professor of the shared understanding of medicine at the Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham.

Competing interests: None declared