Antonio (not his real name) sits in the departure hall in Rome Fiumicino airport. He is one of those guys who wrap your luggage up in plastic. He initially complains about the cancellation of football matches, then of lack of business, until finally we get down to the real issue. The lockdown of the economic powerhouse of Lombardy, Italy, is going to hit us hard and tourism will take a long time to recover from the “plague capital of Europe” image. I breeze through security and passport control in the semi-deserted terminal. No additional checks, no questions asked. At the bar I catch a conversation among airport workers. The mood is changing from one of incredulity and puzzlement to one of anger. Anger at what they see as overreaction and victimisation.

The aircraft is half empty too: out of 208 seats only 110 are occupied—an unheard of occurrence on this usually very busy flight from Rome to London. Once I explain what I do for a living the stewardesses ask me the usual: how is this different from garden variety influenza-like illness (which they call “the flu”, the F word I never use)? By now I have become an expert at evading the question, as I do not know the answer.

The aircraft is half empty too: out of 208 seats only 110 are occupied—an unheard of occurrence on this usually very busy flight from Rome to London. Once I explain what I do for a living the stewardesses ask me the usual: how is this different from garden variety influenza-like illness (which they call “the flu”, the F word I never use)? By now I have become an expert at evading the question, as I do not know the answer.

When we get to Heathrow I breeze through arrivals, again no questions asked. Just before taking off from Rome I check that I could have got a flight from Milan, to Fiumicino (Rome) and then onto Heathrow. I could have—and it’s cheap (about 36 Euros). Airlines must be getting desperate.

When we get to Heathrow I breeze through arrivals, again no questions asked. Just before taking off from Rome I check that I could have got a flight from Milan, to Fiumicino (Rome) and then onto Heathrow. I could have—and it’s cheap (about 36 Euros). Airlines must be getting desperate.

So I could have arrived in Heathrow from Milan without any checks.

When I get to Oxford I meet up with my colleagues, a mixture of serious evidence based medicine academics. None of us has an answer to the question of what is different this time with this pandemic.

Three days later I am on my journey back: 39 people in 180 seats.

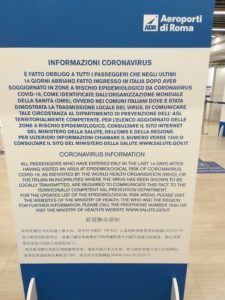

On arrival at Fiumicino we are greeted by a bilingual sign manned by a member of the army and two healthcare workers all in masks and red cross suits. They are there apparently waiting for any of us to tell them whether we are from a WHO-declared risk zone. I am struck by the hands down and honest approach, but in these cases I am not sure whether relying on other folk’s honesty (with a prospect of 14 day quarantine) is a good idea. Further on in the deserted Terminal 3 there is a hand sanitizer dispenser.

On arrival at Fiumicino we are greeted by a bilingual sign manned by a member of the army and two healthcare workers all in masks and red cross suits. They are there apparently waiting for any of us to tell them whether we are from a WHO-declared risk zone. I am struck by the hands down and honest approach, but in these cases I am not sure whether relying on other folk’s honesty (with a prospect of 14 day quarantine) is a good idea. Further on in the deserted Terminal 3 there is a hand sanitizer dispenser.

While I was away the situation has evolved and perceptions have changed. Travel restrictions, schools and public places closures have been imposed on the whole country. Italy is in lockdown. There have been runs of supermarkets and toilet paper and disinfectants are at a premium. Antonio is nowhere to be seen, perhaps he has packed up for the duration.

Tom Jefferson is an an epidemiologist and Cochrane researcher, based in Rome, Italy.

Competing interests: Please see full statement here