Canadian family physician Antoine Boivin and patient partner Ghislaine Rouly describe how they work together with community partners to provide holistic care for patients with challenging social and medical problems

Antoine Boivin—the physician’s perspective

As a physician working in a primary care group practice of 12 000 patients, in a disadvantaged neighborhood of Montreal (Canada), I have often had the feeling of being the “right answer to the wrong problem.” Many of my patients present with medical symptoms (depression, chronic pain, fatigue and anxiety) that are exacerbated by underlying social problems (isolation, poverty, divorce, bereavement, stress, violence or work difficulties). I can sometimes refer those patients to a social worker or psychotherapist, but for many, this is met with suspicion (“You mean it’s in my head?”), resistance (“I’ve seen a shrink before and it didn’t help”) or practical barriers (“I don’t have the money”). Most of all, I feel that health professionals are a poor substitute for a caring friend, family member, or neighbour. It was keen awareness of these issues that prompted me to approach Ghislaine, a much trusted and valued patient partner at our University of Montreal partnership programme, to adopt a new way of caring for patients together. [1] Her extensive knowledge as a patient and caregiver, her ability to listen without judgement, her humility and her diplomatic skills gave me confidence that working together we could deliver what I could not do alone.

Ghislaine Rouly—the patients perspective

I have been a patient all my life as I was born with two genetic diseases, and have subsequently had three major cancers, for which I have experienced months in an induced coma. As a result I live with chronic pain. I have also lost a daughter following the early diagnosis of an incurable disease. Despite all this, I have found that you can lead a good life if you are determined to do so. For me, helping other patients has always been a natural thing to do. For over 45 years, I have provided peer-support to other patients, accompanying them on their healthcare journey until their end of life. My experience has taught me a lot about the importance of being treated with humanity; and how this is especially important for those who are isolated, alone, depressed, and sick. In the past decade, I have trained health professionals in medical ethics, health communication, and collaboration, based on my lived experience as a patient.

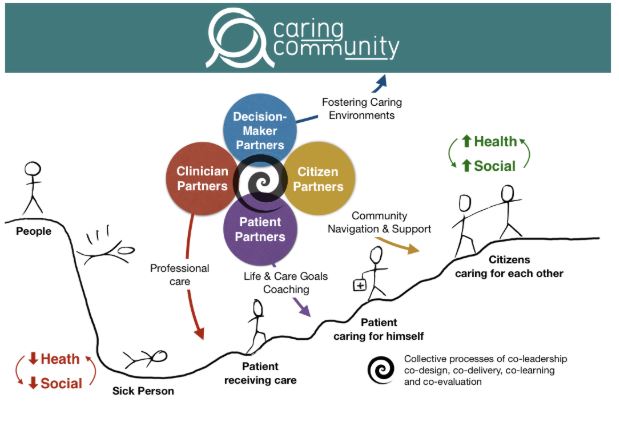

Four years ago I joined Antoine’s practice as a patient partner, working three days a week with him on a salaried position to care for patients together. We co-designed and co-lead the Caring Community project where patients, professionals and citizens work as partners to bridge medical and social care for people with complex conditions in the community. I was touched by Antoine’s humanity, humility, and concern for his patients. It was clear from the outset that we shared common values and a dream of caring for patients differently, drawing on our complementary skills.

“Crossing the river by feeling for stones”: the nuts and bolts of caring together [2]

Antoine: Our partnership is guided by mutual trust in each other, inspiration from other international initiatives, and a shared belief that we can care better together. [3,4,5]

Our approach is very simple. First, I identify patients whom I believe would benefit from Ghislaine’s expertise and support as a patient partner, when social issues complicate the care of medical problems, and vice-versa. Unlike disease-based peer-support programmes, I do not try to match Ghislaine with people who have similar health issues. My first cue is a feeling of being limited in my ability to find professional solutions to the presenting problem, either because of patients’ difficulties to play an active role in their care, low adherence to treatment and follow-up, or social challenges that I am powerless to address only within the professional health system. Sometimes, I simply don’t understand what the real problem is, I cannot fit it into a medical diagnosis and I need someone else to listen with different ears.

When I offer my patients to meet with Ghislaine, I introduce her as a “patient partner” working with me. I explain that she has a lot of experience being a patient herself and helping other patients develop their own skills, navigate inside the health system, and reconnect with their own community. Most of the time, patients are surprised, a bit puzzled, but keen to give it a try. We have followed over 20 patients together and it happened only once that the family of one of my patients insisted that only professionals be involved in the care of their mother.

When patients accept, we book an initial joint appointment at the clinic on a day where Ghislaine and I are present. I do a short face-to-face introduction to launch the relationship, summarize the reason for referral, and illustrate that Ghislaine and I work together as trusted team members. This short, 5 to 10 minute face-to-face connection is critical and lays the foundation for Ghislaine’s work. While many of my patients resist seeking help from community resources through simple social prescription and referral to a community organization, we have observed patients’ willingness to “trust someone their doctor trusts and works with.”

We keep paperwork to a minimum. We’ve established that mutual confidentiality should be maintained. Ghislaine has no access to patients’ medical files, while clinical staff have no access to what patients’ share with patient partners, unless there is an emergency (eg. suicidal ideas) or patient’s request to share relevant information that would help improve their care (eg. share new symptoms that they were shy to express directly to their clinicians). We also ask that patients respect confidentiality and do not disclose personal experiences shared by patient partners. These simple rules of engagement to reassure people that their medical file remains private. It creates a new confidential space to share personal concerns with the patient partner acting as a non-judgmental peer, revealing issues that are often not disclosed to health providers, but profoundly affect their care and wellbeing. Once trustful relationships are established, patients can be empowered to share the right information with the right clinician or caregiver, to ensure that their care is truly aligned with their own goals and priorities.

Ghislaine: There are three facets to my work: listening, coaching, and connecting. My first meeting with the patient focuses on listening and understanding who the patient is as a person and what challenges they are experiencing in their life. My opening line is often: “Who are you as a person and how could I help you to achieve your goals today?” I listen, often for an hour or more, without trying to find a solution. For many, this is like a dam that is breaking up. It is impressive to hear the intimate stories that are shared with me during that very first meeting and that have often not been told to anyone else: childhood abuse, unexpressed sexual orientation, drug use, poverty, financial and family abuse, fear of death and loss of autonomy. One of the patients said that meeting me made him feel that he was “having someone at his side”, as opposed to having a professional “sitting on the other side” of the desk.

In follow-up meetings (which can be arranged at the clinic, in cafes, at home, in the hospital, or in the community) I help patients identify and achieve a personal life goal that is important, feasible, and realistic for them. Patients’ goals can relate to their health (eg. reduce my pain to sleep better, reduce my visits to the hospital to spend more time with my grand-daughter, get a dental implant to improve my self-esteem) or social goals (eg. get out of my house 3 times a week to meet people and feel less lonely). We identify what resources they have in themselves and in their support network to achieve these goals (their health professionals, family, community members). I am struck by two things here. First, people often choose goals that have nothing to do with their disease and start thinking about themselves beyond their identity as a patient. Rapidly, the conversation switches from “what can others do for my health” to “what can I achieve with others for myself”. Second, I am often impressed by what patients can achieve after 1 or 2 meetings (eg. a patient who felt more confident to express her needs to her pain specialist, another who was stuck in her home for years who rapidly started to socialize and involve herself in community groups).

A third component of my work is the “connecting role.” I help patients recognise and rediscover their own strengths, capacities, and dreams, rather than seeing only their disease, their losses, and the barriers around them. I also facilitate a reconnection between patients and their family, friends, and their natural support network which they often abandon once they get sick, either because of shame or fear of being a burden. I also help them connect more effectively with their clinicians, have the courage to express their needs and concerns (eg. talk about the side effects of medication), and guide them toward other health professionals such as a social worker or psychologist. Finally, I help connect them to their broader community (eg. leisure and cultural activities, support groups, voluntary organizations): who are likely to help them achieve their life goals. This part of my work is developed jointly with “citizen partners” working with us and helping connect clinical care to community life.

Extending care beyond the clinic walls

Recently, we have expanded our Caring Community team to include “citizen partners”, people with experience of engagement in their own community who have a deep understanding of local social life, activities, and organizations. Citizen partners act as community navigators, helping people connect with other citizens and community resources. Providing care and support in conjunction with engaged citizens has helped us identify housing, employment and food resources for disadvantaged patients; foster links with community support groups; helped us to “link-out” patients from the clinic to the community to address their social needs; but also to “link-in” community members with unaddressed health issues by helping them to access the healthcare system with support from our patients and clinician partners.

A diverse team of clinicians, patients and citizens caring together

In our Caring Community, each of us brings different and complementary expertise to provide care based on common values and principles: clinician partners are experts of disease management, patient partners are experts in learning to live a full life beyond the consequences of their disease, and citizen partners are experts in facilitating social inclusion and participation in the community. Our Caring Community team now includes a dozen primary care professionals (four physicians, two nurses, a social worker, a psychologist, and a clinical ethicist) and a team of five patient and citizen partners (with personal experience of different chronic conditions, self-management support, peer-support, and citizen engagement with community organizations for homeless people, women’s groups, immigrants, and elderly people living alone). In the past year, a second primary care clinic has joined the project and applied for further funding with us. Our local health authority has established collaborations between Caring Community and a variety of its local health and community programs (primary care, mental health, homelessness and addiction, home care, geriatrics, and public health). Caring Community is slowly growing into a generic bridge between local health and community care.

Illustrating the potential for improved healthcare and social impact

Four years down the road, these are still early days for the Caring Community project and we are far from a randomized trial publication in The BMJ. Nonetheless, our experience suggests the potential of our approach to improve health and social outcomes for patients with complex needs, as this anonymised real case illustrates (patient consent obtained):

Antoine: “George” is a 50-year old man with heart failure, uncontrolled diabetes, renal insufficiency and drug use. Over a two-year period, he was hospitalized five times, and rarely showed up to his appointments. Mobilizing the full interdisciplinary team had proved ineffective (family physician, nurse practitioner, social worker, pharmacist, endocrinologist and cardiologist). He refused medical home visits. As professionals, we all felt trapped in a clinical dead-end.

Ghislaine: When Antoine introduced me to George. I quickly established a connection by listening to him as a person (rather than interrogating him as a patient) I emphasised that I was not a health professional, but simply a patient wanting to get to know him. I identified that his most pressing priority was to balance his precarious finances and connected him with a community organization that could provide food coupons and clothes for him and his family. I understood that George’s life goal was to witness his grand-daughter growing-up. I understood his fear of losing sight from diabetes, his difficulties to pay for transportation for his medical appointments, his apprehension of social workers because of previous difficulties with child care services, and his resistance to allow home care nurses into his apartment because he was ashamed of it. I visited him several times during an hospitalization, coached him on how to interact with health professionals (eg. replace cursing by firm and respectful assertion of his needs), established contact with his family to clarify their roles, orchestrated a meeting with the clinic’s interdisciplinary team, and I was the first person to be invited into his home.

Antoine: After a single month, Ghislaine was the person who had established the highest level of trust with George. Building a solid relationship with a patient partner like Ghislaine, and expanding our care team with community organizations, unlocked what our team saw as an intractable problem and helped us build true care partnership with George and his family. Since then, our primary care team had over 30 clinical interactions with George (either face-to-face and over the phone); he accepted weekly home care visits with a nurse to monitor his diabetes and heart failure; his family members have become allies for medical care; and he is my only patient to text me his lab results and questions. In the past year, he had no hospitalization and not a single visit to the emergency room, a saving of 15 000$CAN/year for our health system and a tangible gain for George’s wellbeing, aligned with emerging evidence on the impact of similar interventions on hospitalization and costs. [6,7] I do not know of a single pill with such impressive results for my patients.

Key learning and next steps

Ghislaine: At the beginning of the project, professionals were telling me that as long as I was here, everything would be fine: but how can we clone you? There is no need for that. There are many patients with great experiential knowledge and engaged citizens with deep knowledge of their community. It is natural and instinctive that people help each other. We have identified such patients and citizen partners in the past year to join our project: we bring them together, support them, and build a team.

Antoine: This project has reminded me that healthcare, in its essence, is about building caring relationships and seeing patients as people with knowledge, skills and life projects. I have learned that it is feasible to integrate patients and citizens as members of the team. However, this requires time, patience, and sensitivity to professional resistance and fears. It is possible to build a two-way bridge between the health system and communities. However, keeping a project like this alive is a tough balancing act. Currently, the most pressing questions in front of us are:

- How to build Caring Communities with patients and citizens in a way that is equitable and inclusive, ensuring that we mobilize a diversity of patients, clinicians and citizens who recognize the specific knowledge of everyone involved, and work toward a common goal?

- How to fund, lead and implement Caring Communities with health and community organisations in a way that is adaptable, sustainable and scalable to other contexts?

- How to rigorously assess the impacts of caring with patients and communities on health and social outcomes? What are the main risks, costs and pitfalls? At this stage, individual cases can help us build an intervention theory and hypothesis. Our next research focus will be to strengthen impact evaluation with more robust designs.

For me, the most important take home message from this initiative so far is that caring with patients and citizens is feasible, enjoyable, natural, and helps refocus care on what matters most to people.

Antoine Boivin holds the Canada Research Chair in Patient and Public Partnership and is associate professor of family medicine at Université de Montreal. He is the co-founder and scientific director of the Center of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public and the Caring Community project. His medical practice is at Notre-Dame Family Medicine Group (CIUSSS Centre-Sud de Montreal).

Ghislaine Rouly is a patient partner with the Canada Research Chair in Patient and Public Partnership and Center of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public. She is the co-founder and co-lead of the Caring Community research-action project.

Competing interests: None declared

Patient consent obtained

References:

1. Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Academic Medicine. 2015;90(4):437-441.

2. We borrowed the “crossing the river by feeling for stone” image from social innovator Adam Kahane, who suggests that tackling complex problems require us to cocreate our way forward. “We cannot know our route before we set out; we cannot predict or control it; we can only discover it along the way…In this context, the only sensible way to move forward is to take one step at a time and learn as we go”. Adam Kahane. Collaborating with the ennemy. Chapter 6, p. 75-76. Berrett-Koehler editors, 2017.

3. O’Mara-Eves, A., Brunton, G., McDaid, D., Oliver, S., Kavanagh, J., Jamal, F., et al. (2013). Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research, 1(4), 1–526. http://doi.org/10.3310/phr01040

4. Lewin, S., Munabi-Babigumira, S., Glenton, C., Daniels, K., Bosch-Capblanch, X., van Wyk, B. E., et al. (2010). Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 94(0803-5253 (Prin), 1109–4. http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3

5. Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392–411. http://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947

6. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Cost of a Standard Hospital Stay (2017-2018). Retrieved on November 19th, 2019 from: https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/

7. Abel, J., Kingston, H., Scally, A., Hartnoll, J., Hannam, G., Thomson-Moore, A., & Kellehear, A. (2018). Reducing emergency hospital admissions: a population health complex intervention of an enhanced model of primary care and compassionate communities. Br J Gen Pract, 68(676), e803–e810. http://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X699437