Healthcare professionals should stop using BMI as the sole measure of an eating disorder, says Hope Virgo

If I ask you to imagine an anorexic person, I can almost guarantee that the first image that comes into your head is of a girl, probably around puberty, who looks extremely gaunt, bones slightly jutting out. This is the image that comes to so many of us when we think of someone with anorexia, but it is this perception that risks people with eating disorders not reaching out for support or, when they do, not receiving it. For me, this worry was realised when I went to the doctor for help, only to be told: “You aren’t thin enough . . . ”

When you get a response like this it not only plays up to the stigma of people with an eating disorder looking a certain way, it also reinforces that complete and utter fear that many people with anorexia have that you aren’t “good enough” at being anorexic and that you don’t look thin. It triggers and substantiates a lot of negative thinking, and when coming from someone in a position of authority who you should be able to trust, it feels so much worse. My body image was completely distorted and being told I wasn’t thin enough amplified that body distortion.

I developed anorexia when I was 13 years old and the anorexia became like having a best friend with me all the time. It gave me value and a sense of purpose that I wasn’t getting from anywhere else. I didn’t realise how dangerous what I was doing was or that I had anything wrong with me at all. Fast track to when I was 17 sitting in bed in a mental health hospital: my heart had nearly stopped, my hair was thinning, and I was about to begin the hardest year of my life. After that year in hospital I was discharged and knew what I had to do to maintain my recovery.

Yet the thing about mental illness is that if you don’t manage it in the right way, and if you aren’t aware of your coping mechanisms and triggers, then there may be a point at which it returns. Unfortunately for me, in 2016 after being out of hospital and managing my recovery, I relapsed.

The frustrating thing was that I knew what was happening. I was determined to not end up in adult services as an inpatient so I knew I had to do something. I referred myself to adult services and got an appointment at an eating disorder unit. I had thought that this would be the hardest step but then I was told “I wasn’t thin enough for support.”

I left the appointment not sure what to do. I had wanted someone to take my relapse seriously and give me some help. Yet now I felt like a fake.

Unfortunately, this is not something that just happened to me; the more I shared my story, the more I realised that this is a frequent occurrence on the NHS. A parliamentary select committee recently heard from a number of witnesses who reported that GPs were overly reliant on low BMI as an indicator of an eating disorder. It is clearly not right that people are being turned away because of their BMI, nor is it consistent with current recommendations.

NICE guidelines currently advise that healthcare professionals ”Do not use single measures such as BMI or duration of illness to determine whether to offer treatment for an eating disorder.” Yet this is not always being followed—at the cost of patients’ health and wellbeing.

We know that early diagnosis is critical to successfully treating eating disorders. By the time the “obvious” signs of an eating disorder have manifested, it is likely that the illness, along with its associated behaviours and thoughts, will have become more ingrained in the individual, making it more difficult to treat. If we want to prevent people from becoming seriously ill, we need to make sure that all frontline staff have a clear understanding of the guidelines and why it’s important to not use BMI as the sole measure of an eating disorder.

If we tackled this and changed healthcare policy and public understanding around eating disorders, the benefits would be huge. We would be able to prevent the decline in health and even death among people with eating disorders, prevent hospital admissions, and save the NHS money. We know that people with eating disorders experience a worsening cognitive decline the more weight they lose, which lengthens their recovery time. If we had early intervention this would mean that people would have a higher success rate in recovery.

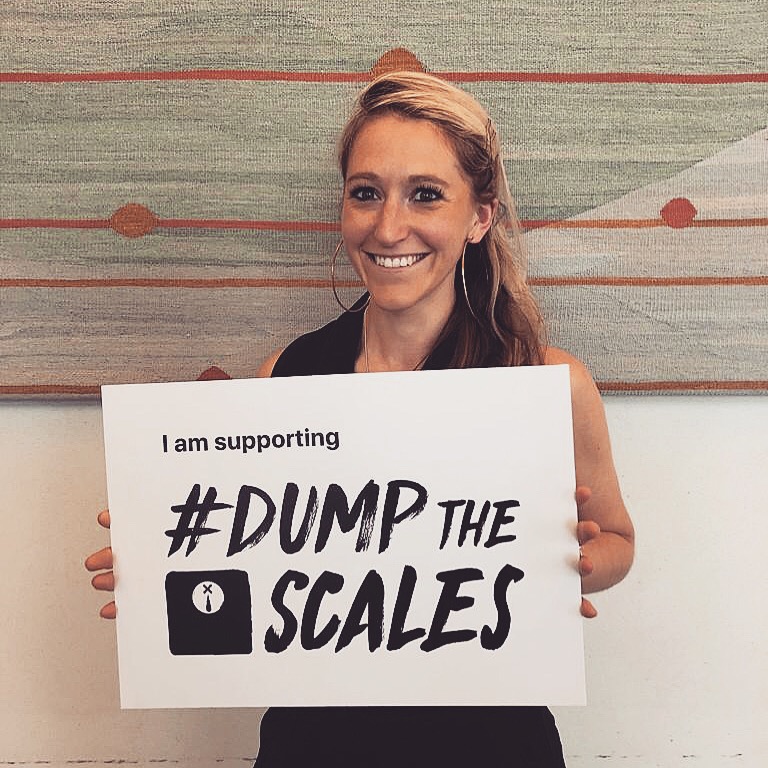

Knowing how crucial early treatment is and hearing how other people had experienced similar treatment by healthcare professionals, I began the campaign #DumpTheScales. This calls for doctors to stop focusing disproportionately on weight when diagnosing and treating eating disorders. It is a call that was echoed last week by the aforementioned parliamentary select committee that has been hearing evidence on eating disorders. Their latest inquiry recommends that doctors avoid using “single measures such as BMI” and that they receive more training on eating disorders.

Better training would go a long way to improving doctors’ understanding of the disease, but there are already steps that individual doctors can take. We need to look at patients as individuals. For doctors, this means being mindful of what you say to your patients when they come in displaying signs of eating disorders, listening in a non-judgmental way, and taking their concerns seriously.

The UK has the right guidelines, but they are not being uniformly followed. It is time we stopped waiting for people to hit crisis point before we offer them support.

Hope Virgo is the author of Stand Tall Little Girl and an international advocate for people with eating disorders. Hope helps young people and employers (including schools, hospitals, and businesses) to deal with the rising tide of mental health issues.

Competing interests: I gave evidence to the parliamentary select committee referred to in this article. Nothing further to declare.