Jean Straus describes a co-produced project to help raise awareness of hearing loss

“Good sensory health provides the fuel for cognition. It keeps us fully present and able to participate fully in our lives and communities.” [1] This quote is so obviously true as to almost be self-evident. And yet having good sensory health, or good hearing health, can be hard to come by when we might be at our most vulnerable, for example, in health or social care settings.

I have hearing loss. When a doctor is giving me a diagnosis, hearing it can be difficult, especially if the consultation is happening inside a curtained off cubicle surrounded by other curtained off cubicles, which creates a loud volume of background noise. This happened to me recently in an ENT clinic, of all places! It was so noisy that not only could I not hear the advice that was being offered to me, but I wanted to leave as soon as possible, just to get away from all the noise and the challenge that this was posing to me. If a pharmacist is explaining how I should take a medication, but they are looking at a computer screen, rather than directly at me, or they cover their mouth when they speak, or they don’t take note that I am struggling to hear, then I worry that I won’t know how to take the medication properly. Whose responsibility will it be if I get it wrong? Other times that I struggle are when I am waiting to be called into a GP appointment, tensely worried I won’t hear my name being called. Patients have been known to miss appointments.

During a recent James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership looking to make care safer for adults with complex health needs, patients highlighted how improving communication between healthcare professionals and people with communication difficulties is a key area where research is needed to improve care. One of the groups included those who are deaf and hard of hearing.

The secretariat of this Priority Setting Partnership, Anna Lawrence-Jones from NIHR Imperial PSTRC, spotted an excellent opportunity to bring different people together to improve communication for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss and health/social care professionals. With support from the UCL Centre for Co-Production in Health Research (funded by Wellcome), a diverse Steering Group (people with hearing loss, clinicians, patient involvement experts, voluntary sector and researchers) co-created a “Sandpit Innovation Workshop,” wherein a group of 30 people with diverse expertise and backgrounds came together for a couple of days to come up with their own solutions and work them up together. We gave the participants space to think, found some inspirational speakers, had rounds of feedback, and a multidisciplinary panel to decide which newly-forged team would win funding for their idea. This model combined co-production with a way of helping people with hearing loss.

I was part of this Steering Group. I already had experience of working on multiple healthcare and research projects because I have a condition which came on suddenly—Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Stymied by the lack of knowledge surrounding the increasingly debilitating accumulation of hearing loss, tinnitus, and loss of pitch (diplacusis), I started getting involved, as a writer, speaker, volunteer, patient and participant in research. If I could help other people, I felt I was a less passive recipient of my own condition. I am an NIHR NWL CLAHRC Fellow, and I was put forward as a patient who could help to co-produce the event, including ensuring the event had appropriate support for people with hearing loss, promoting the event through my many networks, and being part of the panel to make the final funding decision.

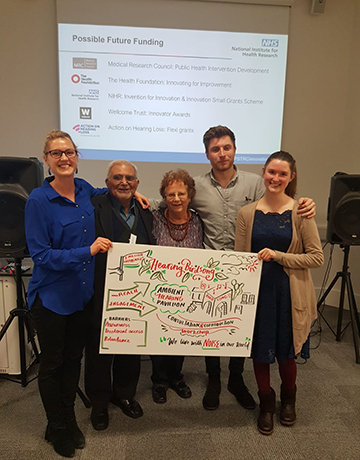

The event was a great success and showed how if an event is co-designed, patients—who are often excluded from events like this—can be involved. We had a palantypist, so that those who couldn’t hear the conversation could read what was said in real time. We had a Scribe who made illustrated panels of each of the ideas, to help the teams visualise their concepts and pitch them. What was particularly rewarding about the competitive element was that, before the final pitches were delivered, all the participants offered each other suggestions for refining their projects. This created an atmosphere of constructive criticism and joint ownership rather than all-out competition.

Hearing Birdsong was the project that won £5,000 from NIHR Imperial PSTRC to take forward their idea. Birdsong is one of the sounds that many people say they miss most when they lose their hearing. Tom Woods, a product designer and co-director of Kennedy Woods Architecture, listened to Angela Quilley describe how she finally decided to attend to her hearing loss when she realised that she could no longer hear birdsong. Inspired by this, he and she worked together with a researcher from NIHR Imperial PSTRC and a clinician to develop this personal experience into a concept to encourage others, in a non-threatening way, to seek help if they are experiencing hearing loss.

The project brings together art and science, by using the iconic bird box and familiar bird songs (at different frequencies) with woodland background noise, to encourage conversations about hearing loss in a safe space. If visitors are unsure if they can hear the different birds, trained staff will be on hand for discussions and to sign-post to further information or support. To tie in with World Hearing Day, the team are holding a free exhibition on 8th March at the Helix Centre for Design pop-up box at St Mary’s Hospital, London for the public to interact with the beautifully designed bird boxes and give feedback on the concept for further development. Ultimately, the project is aiming to support early diagnosis and intervention, which we hope will lead to better communication for the millions of people with unaddressed hearing loss.

The project brings together art and science, by using the iconic bird box and familiar bird songs (at different frequencies) with woodland background noise, to encourage conversations about hearing loss in a safe space. If visitors are unsure if they can hear the different birds, trained staff will be on hand for discussions and to sign-post to further information or support. To tie in with World Hearing Day, the team are holding a free exhibition on 8th March at the Helix Centre for Design pop-up box at St Mary’s Hospital, London for the public to interact with the beautifully designed bird boxes and give feedback on the concept for further development. Ultimately, the project is aiming to support early diagnosis and intervention, which we hope will lead to better communication for the millions of people with unaddressed hearing loss.

I think there are hidden reasons why many of us have been so taken with this endeavour. There has long been a disparity between the number of people with hearing loss who do something about it and those who let it go or deny it. We know that on average it takes ten years before people aware of their hearing loss begin wearing hearing aids. We know that the longer you wait, the less able you are to adapt to them.

Nevertheless, once we own up, and get our hearing checked, we enter an antiquated system to which audiologists are so bound that patients can at times feel as if we’re being herded through a system. We come in to a room, are then led into a closed cubicle with heavy earphones over our ears, where we are made to listen to mechanical beeps and push on a button. It can feel harsh, impersonal, and stressful, because our natural inclination is to want to pass a test. We want to hear those beeps. Then when we don’t, somehow we feel like failures.

Hearing birdsong feels humane. It acknowledges we have hearing preferences. It is gentle. Yes, it can still be stressful to discover we’re not hearing the birdsong, but at least it’s a sound we want to hear. I hope that the Hearing Birdsong project will raise awareness of hearing loss and encourage people to seek help and treatment earlier.

Some of the other ideas from the event are also ongoing and aim to improve communication between clinicians and adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. The Let’s Talk project will produce a platform where people with hearing loss can easily create a personalised credit-sized card to hand to a professional they are trying to communicate with, containing short explanations of how they hear best, for example: “Please talk slowly” or “Face me”.

The Empathy Simulator project will produce a digital tool that offers care staff an immersive experience of hearing loss in care settings, in order to generate greater empathy and understanding. Unlike the usual method of blocking sound out to show people what deafness is like, this tool will simulate real-life situations. Ideally, as part of their training, care home staff, for example, would be able to sense what a resident’s hearing is like when they’re sitting in a communal space.

The Hearing Screening of People with Memory Loss project aims to screen people for hearing loss while attending memory clinics: dementia and hearing loss are often confused. The quality of life for people with dementia can also be improved when their hearing has been attended to.

All of these innovative projects have materialised because co-production was valued and patients, out-of-the-box thinkers and clinicians were involved in coming up with the ideas and developing the projects. I hope that they will bring about meaningful change for people with mild to moderate hearing loss and raise awareness of the challenges that people face.

Jean Straus is a volunteer at Action on Hearing Loss. She was a Steering Group member on the James Lind Alliance PSP. She has been a NIHR NWL CLAHRC Patient Fellow and is currently on the Access to Good Sensory Health Group, a NHS England/CSO Office-led Steering Group.

Jean Straus is a volunteer at Action on Hearing Loss. She was a Steering Group member on the James Lind Alliance PSP. She has been a NIHR NWL CLAHRC Patient Fellow and is currently on the Access to Good Sensory Health Group, a NHS England/CSO Office-led Steering Group.

Competing interests: None declared.

Footnote:

1] Adrian Davis, OBE, Advocate for Sensory Health