The Cochrane Collaboration’s conflict of interest policy is currently undergoing a regular update. I welcome this update and the call to strengthen the policy. [1] Cochrane publishes systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). A number of decisions are made during the design and conduct of a systematic review and these could be influenced by conflicts of interest. Funding sources and author conflicts of interest are associated with favourable outcomes for the sponsors of systematic reviews. [2] Decisions are also made when designing and conducting clinical trials, including framing the question, and the selection of methods, analysis, and outcomes. These decisions can bias the results of a trial and funding sources and author conflicts of interest are associated with favourable results of drug industry sponsored trials. [3] Evidence supports strengthening conflict of interest policies related to systematic reviews and primary research.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s conflict of interest policy is currently undergoing a regular update. I welcome this update and the call to strengthen the policy. [1] Cochrane publishes systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). A number of decisions are made during the design and conduct of a systematic review and these could be influenced by conflicts of interest. Funding sources and author conflicts of interest are associated with favourable outcomes for the sponsors of systematic reviews. [2] Decisions are also made when designing and conducting clinical trials, including framing the question, and the selection of methods, analysis, and outcomes. These decisions can bias the results of a trial and funding sources and author conflicts of interest are associated with favourable results of drug industry sponsored trials. [3] Evidence supports strengthening conflict of interest policies related to systematic reviews and primary research.

Most journals subject systematic reviews to the same peer review processes as primary research articles. Cochrane reviews are peer reviewed at the protocol and review stages. Cochrane’s conflict of interest policy for Cochrane reviews, first published as the Commercial Sponsorship Policy in 2004, was informed by journal conflict of interest policies and finalized after a lengthy consultation period among Cochrane members. The policy was last updated in 2014.

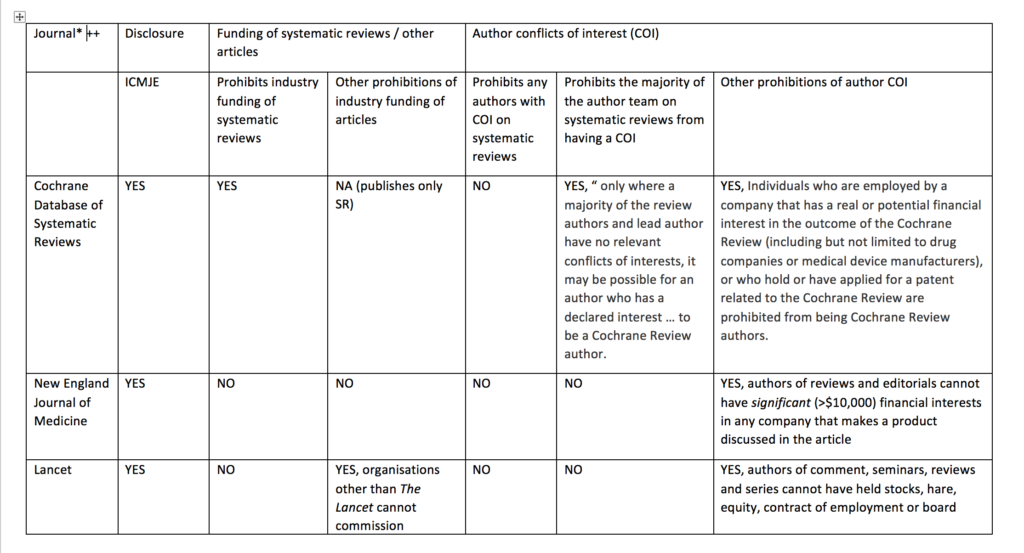

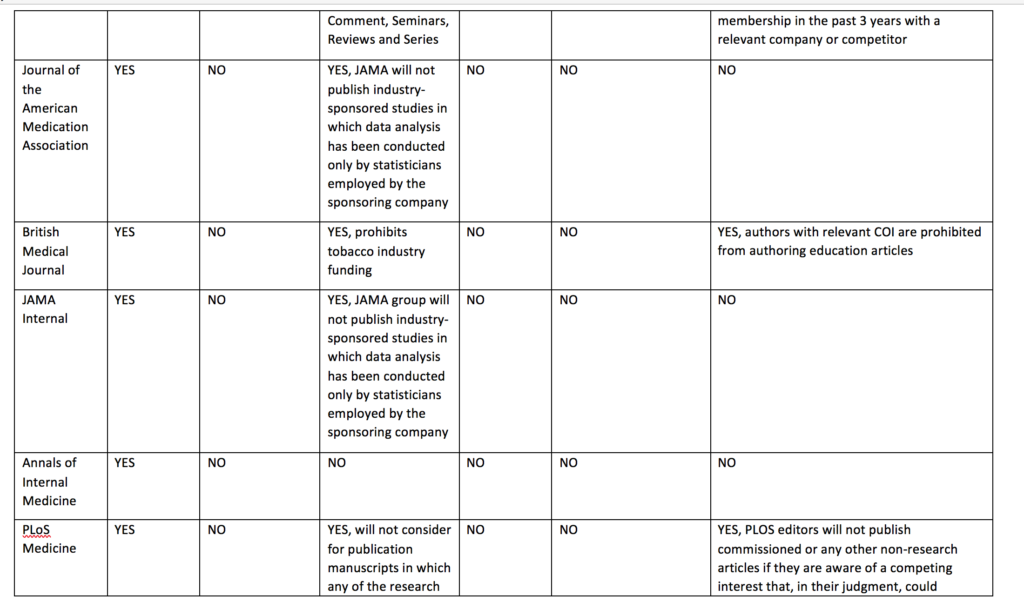

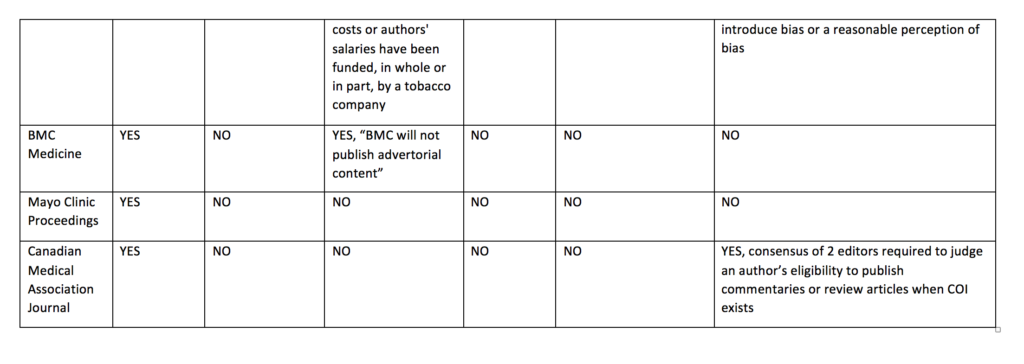

I compared the current published policy for the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to the current published policies of the top 10 journals by impact factor (with >10 000 cites) in 2017 in the Medicine, General & Internal category according to InCites Journal Citation Reports (see table below). This comparison underlines why I think journals should emulate the restrictions used by Cochrane and extend them to other types of primary research articles.

Like the other journals in the sample, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews requires that all authors of Cochrane reviews disclose conflicts of interest according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editor recommendations. For Cochrane reviews, disclosure is required before the publication of a protocol, review, or update.

Cochrane’s policy regarding funding of Cochrane reviews is stricter than other journal policies related to funding of systematic reviews or primary research. Cochrane reviews cannot be funded or commissioned by any commercial sponsors with an interest in the findings of a specific review. For example, a review including medicines as an intervention option cannot be funded by a pharmaceutical company. PLoS Medicine and The BMJ prohibit publication of research funded by only one type of commercial entity—tobacco companies. JAMA and JAMA Internal Medicine will not publish industry sponsored studies in which data analysis has been conducted only by statisticians employed by the sponsoring company.

Cochrane’s policy limiting authors with conflicts of interest is also stricter than the other journals. Cochrane’s policy is that there must be a majority of authors with no conflicts of interest for any particular review and the lead (first) author must have no conflicts. For example, if two authors in a review team have received travel grants from a commercial sponsor, there must be at least three other non-conflicted authors and the lead (first) author must have no conflicts. Examples of financial support that would prohibit someone from being an author of a Cochrane review include, but are not limited to, remuneration from a consultancy, grants, fees, fellowships, support for sabbaticals, royalties, stocks, and advisory board membership. No other journals in the sample prohibit individuals with conflicts of interest from authoring systematic reviews or primary research articles. Other journals do prohibit conflicted authors on opinion pieces, narrative reviews, education articles, and other types of non-research articles.

Cochrane prohibits individuals from being Cochrane review authors who are currently employed or were employed any time in the past three years by a company that has a financial interest in the outcome of the review, or who hold or have applied for a patent related to the review. No other journals in the sample prohibits industry employed individuals from being authors of systematic reviews or primary research articles.

My sample does not measure other types of journal industry interactions that could influence editorial content. For example, in contrast to many other journals, Cochrane does not accept pharmaceutical industry advertising on its websites, the Cochrane Library, or the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Published journal policies may not be the same as what editors actually do. Journal publication practices may be stricter than their policies or implementation of the policies may be inadequate. Policies are only good if they are enforced. Cochrane policy states that Cochrane reviews or protocols that are not in compliance with the conflict of interest policy will be withdrawn after consultation with the funding arbiter and editor in chief. Since 2004, 20 published Cochrane reviews have been withdrawn because they were not in compliance with the Cochrane conflict of interest policy. However, many more reviews do not go through to publication until they comply with policy, or they are never published due to a lack of compliance.

The published policies examined in this sample are implemented based on what authors disclose; and authors do not always disclose relevant conflicts of interest. In my experience as a journal editor and Cochrane funding arbiter, authors have been genuinely confused about, obfuscated, waffled, omitted, and downright lied on their disclosure forms. Detecting undisclosed conflicts of interest is time consuming and can involve reviewing disclosures in an author’s other publications or information obtained from internal company documents. [4,5,6] More recently, it is possible to compare disclosures to information from transparency databases, although these are only available for pharmaceutical company payments. [7] Few journals have the resources to routinely search for undisclosed conflicts of interest and a publicly available database of all financial ties linked to all researcher names would be a solution. [8]

Cochrane should be congratulated and copied, not criticized, for setting a high standard for managing conflicts of interest in systematic reviews. There is a risk that when Cochrane revises its policy, there will be pressure during the comment period to weaken the policy by making it “more like other journals.” Authors have a choice about where to publish systematic reviews and they may prefer to go with an easier option that allows conflicted reviewers. I advocate for Cochrane to keep the bar high. The public wants trusted evidence and the public should be asking why other journals don’t have conflict of interest policies as strict as Cochrane.

Lisa A. Bero, is an expert in examining how science can be influenced and the impact of corporate interests on health research, education and policy. She directs the evidence, policy and influence collaborative research program at the Charles Perkins Centre, with research nodes in bias, evidence synthesis and pharmaceutical policy.

Competing interests: I am full time employee of The University of Sydney. I was Senior Editor, Tobacco Control 2000 – 2009, for which I received remuneration. I contributed to drafting and revising Cochrane’s initial conflict of interest policy and read the comments on the policy. I served as Funding Arbiter from 2006 – 2010. I served as Co-chair Cochrane Governing Board 2013-2017, for which the University of Sydney received remuneration. From 2018, I have been Senior Editor, Cochrane Public Health Network, for which the University of Sydney receives remuneration. I will contribute to revising Cochrane’s conflict of interest policy in the future. I conceived of this opinion and wrote it. The opinions expressed are mine alone and not the views of Cochrane.

References:

- Moynihan, R. Let’s stop the burning and bleeding at Cochrane – there’s too much at stake. September 17, 2018. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/09/17/ray-moynihan-lets-stop-the-burning-and-the-bleeding-at-cochrane-theres-too-much-at-stake/

- Hansen, C., Lundh, A., Rasmussen, K., Frandsen, T., Gøtzsche, P., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2017). The Influence of Industry Funding and Other Financial Conflicts of Interest on the Outcomes and Quality of Systematic Reviews. Paper presented at the Peer Review Congress, 10 Sep 2017 Chicago, USA. http://www.peerreviewcongress.org/pdf/2017/prc8-plenary-sunday.pdf (accessed 28 Sep 2017)

- Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 2. Art. No.: MR000033. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3.

- Forsyth S, Odierna DH, Krauth D and Bero L. Conflicts of interest and critiques of the use of systematic reviews in policymaking: An analysis of opinion articles. Systematic Reviews, Nov 2014 18;3(1):122. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-122. PMID: 25417178

- Hong, M-K, and Bero, L. Tobacco industry sponsorship of a book and conflict of interest, Addiction, 2006; 101:1202-1211.

- Steinman, MA, Bero, LA, Chren, M-M, and Landefeld, S. The promotion of Gabapentin: An analysis of internal industry documents, Annals of Internal Medicine, 2006; 145: 284-293.

- Wayant, C, Turnder, E, Meyer, C, Sinnett, P, Vassar, M. Financial conflicts of interest among oncologist authors of reports of clinical drug trials. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(10):1426-1428. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3738

- Dunn, A. Set up a public registry of competing interests. 03 May 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27146998

Table: Comparison of disclosure, article funding and author conflict of policies of major medical journals (n = 11)