We need to transform cultural narratives to address inequalities in medicine

At crucial moments in the history of medicine, fictional narratives about women doctors and surgeons have played a key part in transforming popular and professional opinion. In the 21st century, rising numbers of women are entering the medical profession, but gender imbalances persist. Alongside efforts to tackle structural inequalities, more attention should be paid to how popular culture influences attitudes towards women in medicine.

At crucial moments in the history of medicine, fictional narratives about women doctors and surgeons have played a key part in transforming popular and professional opinion. In the 21st century, rising numbers of women are entering the medical profession, but gender imbalances persist. Alongside efforts to tackle structural inequalities, more attention should be paid to how popular culture influences attitudes towards women in medicine.

By looking at different novels from the late 19th and mid-20th century, we’ll show how these characters have variously reinforced stereotypes and presented positive role models. In doing so, we will demonstrate that while women may have been part of the medical workforce since the 19th century, over the past two hundred years their experiences have been informed by sometimes retrograde and restricting visions of femininity.

Women made inroads into the established medical profession in Britain in the late 19th century. Early pioneers such as Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson paved the way for others, and by 1892 there were 134 registered female practitioners. This period saw a vogue for popular fiction about women in medicine, such as Mona Maclean, Medical Student (1892). Though published under a male pseudonym, it was written by Margaret Todd, a student at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. Her novel drew on her own experiences, while tapping into public interest in the figure of the “New Woman,” who typically favoured education and work over marriage and motherhood.

The novel depicts the medical and romantic adventures of its eponymous heroine. Mona initially fails her exams but after going on a journey of self-discovery she finds a renewed sense of purpose, which allows her to graduate in medicine.Throughout the narrative, Mona grows into a confident and capable doctor, whose close female friendships allow her to build affective bonds with prospective patients. Along the way she falls for a male doctor and the closing scene shows the pair (now married) running a joint practice. Todd departed from popular stereotypes of medical and New Women as androgynous or uninterested in conventional romance.

Mona Maclean proved popular with readers, and was also well received by the medical press. This is surprising, given that many professional journals had initially been hostile towards women entering medicine. The Lancet deemed it “a capital book” and a “well-written, and effectively-told tale.” It judged the story to be “sufficiently medical to give it special interest to medical readers, but not of so professional a character as to diminish its interest for the public.”

By portraying a lively and genteel young woman who finds medical work rewarding, Todd challenged stereotypes that the woman doctor and her chosen career were morbid, instead presenting them as wholesome and respectable. This extraordinarily affirmative novel helped to demystify and humanise the figure of the female doctor.

Following the foundation of the NHS in 1948, and amid wider social pressure to provide equal rights to women, female participation in the labour market expanded, though the “marriage bar”—which curtailed the employment of women after marriage or pregnancy—persisted.

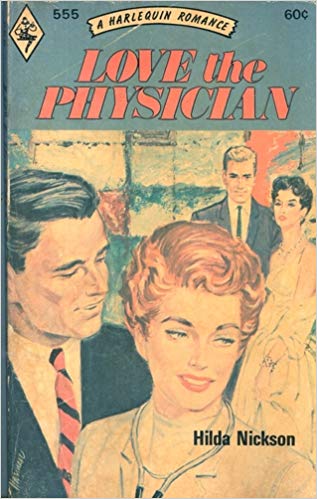

Popular fiction shaped perceptions of the new health service and the role of female professionals within it. Some of the most widely read medical themed fiction of the period were the “Doctor-Nurse” romances published by Mills & Boon. These usually involved love affairs between male doctors and female nurses, set in an NHS hospital, but the heroines were increasingly surgeons and physicians.

The novels were generally written by women with clinical experience. The publishers demanded medical knowledge and accuracy and the texts contain ample technical language and specialist detail. Women surgeons, physicians, and nurses were consistently portrayed as highly skilled—technically excellent clinicians. Describing her surgeon-heroine Madeline, author Hilda Nickson writes, “A love of surgery was in her bones and in her blood as well as in her fingers.”

While these novels assume that women are intellectually equipped for the demands of a medical career, female characters are portrayed as incapable of handling its emotional burdens. The head of one fictional hospital, Dr Benton, makes assumptions about women’s biological fitness for a clinical career: “Personally, I think it’s more natural for a woman to practise obstetrics . . . Many of the patients prefer a woman, and I still believe women have a more sympathetic approach.”

Despite the prevalence of female characters in medical Mills & Boon novels, their presence did little to dispels myths about women’s unsuitability for the medical profession. Technically capable, female doctors were rendered unable to participate effectively in the profession by their gender. Medically skilled but emotionally incontinent, their status and security in the hospital was constantly contested.

The more pessimistic “Doctor-Nurse” romances reflect the realities of being a female doctor in part because they were written by women with ample experience of the medical working world. By contrast, the more optimistic (or idealistic) Mona Maclean presents a woman doctor and her husband working in harmony outside the pressures of the wider medical marketplace, at a time when female practitioners remained anomalous and when fewer female readers would have experienced the pressures of work.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that popular culture shapes people’s interactions with, and expectations of, healthcare and that fiction influences public and professional attitudes towards women in medicine. It creates expectations about what types of women practise medicine and how competently they do so. This affects how medical women are perceived and treated by patients and colleagues.

Images of female practitioners can encourage or deter women from pursuing medical careers. This has profound implications for the future of the profession. Over 150 years since women first joined the medical register, they still face preconceptions that femininity and medical work are incompatible. In order to address persistent inequalities in the profession we need to look to transforming cultural narratives as well as removing structural barriers.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a cultural and medical historian. She is a postdoctoral research fellow on the Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, “Surgery & Emotion,” based at the University of Roehampton. Twitter @agnesjuliet

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a cultural and medical historian. She is a postdoctoral research fellow on the Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, “Surgery & Emotion,” based at the University of Roehampton. Twitter @agnesjuliet

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: My research is funded by the Wellcome Trust as part of the “Surgery & Emotion” Investigator Award.

Alison Moulds is a literary scholar and historian of medicine. She is an engagement fellow on “Surgery & Emotion” and postdoctoral research assistant on the European Research Council funded Diseases of Modern Life project at the University of Oxford. Twitter @alison_moulds

Alison Moulds is a literary scholar and historian of medicine. She is an engagement fellow on “Surgery & Emotion” and postdoctoral research assistant on the European Research Council funded Diseases of Modern Life project at the University of Oxford. Twitter @alison_moulds

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: My research is carried out under funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council.