One of the successes of health workers concerned with climate change has been to get climate change framed as a health issue as well as an environmental issue

Although in most developed countries the health system is a tenth of the economy and so responsible for around a tenth of carbon emissions, NHS England is the only health system in the world to commit itself to lowering its carbon consumption—by 80% by 2050. The Sustainable Development Unit (SDU) is leading achieving this reduction and making the NHS sustainable, and last month it celebrated its first 10 years and paid tribute to its first director, David Pencheon, who has moved on.

Although in most developed countries the health system is a tenth of the economy and so responsible for around a tenth of carbon emissions, NHS England is the only health system in the world to commit itself to lowering its carbon consumption—by 80% by 2050. The Sustainable Development Unit (SDU) is leading achieving this reduction and making the NHS sustainable, and last month it celebrated its first 10 years and paid tribute to its first director, David Pencheon, who has moved on.

Sustainability is about more than carbon reduction, although the reduction is essential for the NHS to be sustainable, and the SDU website has a simple and easily grasped definition of a sustainable health system: “It goes on forever within the limits of financial, social, and environmental resources.” The present system is not sustainable.

The SDU has its origins in a vision of Paul Cosford, who was at the time director of public health for the East of England. He went to see Neil McKay, who was then chief executive of the East of England region, who, as he said at the meeting, had thought little about sustainability. Cosford painted an “irresistible picture” of why something like the SDU was needed. McKay approached other chief executives, and, somewhat to his surprise, they enthusiastically supported the idea and were willing to give money. The SDU was born, and Pencheon was appointed as the first director.

McKay described the output of the SDU as “prodigious” and pointed out that its ideas on how to achieve a sustainable health system with an emphasis on people, communities, health rather than sickness, prevention, public health, information technology, and primary care anticipated The Five Year Forward View, the plan that NHS England is now following.

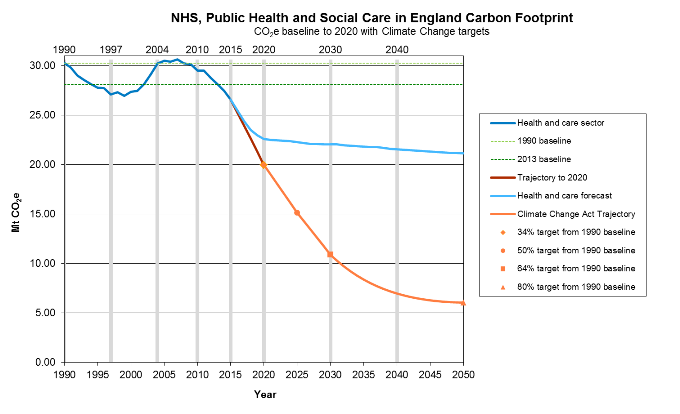

The NHS set a target of reducing carbon consumption by 10% between 2007 and 2015 in order to eventually reach the 80% reduction by 2050, and it achieved an 11% reduction. As the figure taken from the SDU website shows, however, current predictions do not show the NHS achieving its target.

One of the challenges for those concerned about sustainability, and specifically climate change, is to remain positive and optimistic when it’s easy to fall prey to pessimism. As the current issue of the London Review of Books describes, sea level is likely to rise not by three feet by the end of the century, as predicted at the time of the Paris Agreement two years ago, but by 11 feet. Such an increase will submerge many of the world’s major cities and cover most of Bangladesh. Around 145 million people live less than three feet above sea level.

Pencheon, while well aware of the science and the likely consequences of climate change, has always managed to remain positive, and he looked back on what he has learnt.

Some of the lessons have come from what has been learnt campaigning against the harm of tobacco. Most people know that climate change is “dangerous,” but, as with smokers and tobacco, they don’t know how dangerous. Explain to people how dangerous, but at the same time present concrete proposals on how to reduce carbon, and the SDU has produced a route map on how to do so.“Consult and ask” has been a maxim of Pencheon, and the SDU—which has fewer than 10 people—can do its work only through partnership.

One of the successes of health workers concerned with climate change has been to get climate change framed as a health issue as well as an environmental issue. Concern about air quality has been particularly powerful in showing climate change to be a health issue and combining the everyday work of doctors with an environmental issue.

Pencheon also shared the story of a different link between climate change and health that he learnt from Eric Chivian, an American physician and one of the early leaders of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its work in reducing the chances of a nuclear war. Chivian says it’s important to speak up for others species and tells of cone snails, which live on coral reefs and are threatened with extinction. There are around 700 species of these snails, and each species produces 100-200 toxic peptides, some of which have powerful pharmaceutical benefits. Ziconotide, for example, seems to be a thousand times more powerful than morphine and non-addictive. Without action, the cone snails will be lost together with a pharmaceutical treasure trove.

Pencheon has found, however, that motivating people like doctors who “do good every day” to work on climate change has been hard: “I spend my days saving lives, I can’t spend my evenings and weekends saving the planet.” Pencheon has found from a colleague in the Church of England that this is the same with priests, whereas rich businessmen, worried about their place in heaven or at least their legacy, are willing to do more. Nevertheless, the UK Alliance on Climate Change, which the SDU has encouraged, includes nine royal colleges as well as the BMA, The BMJ, and others.

“Emotions drive people, and people drive change,” observed Pencheon, who has always looked for ways to engage people’s emotions. He has worked with groups as varied as psychoanalysts and comedians. Humour is powerful, and he shared the picture of a bicycle (“This one runs on fat and saves you money”) and a car (“This one runs on money and makes you fat”).

Pencheon was delighted to be attacked by the comic Jeremy Clarkson in his column in The Times headed “Come quickly, nurse, the NHS is going frightfully green.” The article outlined the programme of the SDU, condemning every proposal, and ended: “Its quite frankly deluded boss, Dr David Pencheon, says that in a low carbon future, healthcare will not look anything like it does today. You’re damn right, sunshine. The hospitals will be full to overflowing with people who are dead.”

Ending on an optimistic note, Pencheon described how the entrepreneur Elon Musk had promised South Australia to deliver a battery that could store energy generated from wind and capable of powering 30 000 homes in “100 days or its free” and delivered it in 63 days. Change can happen fast. Pencheon also said how solar energy from a small area of Africa could provide power for all of Europe and at the same time provide income, crops, and food for Africa, linking perhaps the two great barriers to universal health: poverty and environmental degradation.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: RS and David Pencheon are friends and go walking together regularly.