When eminent senior doctors—who have a keen and known interest in medical ethics—leave a courtroom threatening to quit the General Medical Council (GMC) so that their money can’t be used to scapegoat trainees, it leaves a sense of how little confidence the profession has in their regulator.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has put out a statement: “Loss of confidence in the General Medical Council would diminish their authority as a regulator, the respect in which they are held, and ultimately their ability to protect patients,” it said.

But that seems to matter little. It’s the public whose confidence in the profession the GMC has a duty to uphold, its QC opined at the High Court in London on 7th December—a point recognised by the RCPCH.

But in the fight to maintain “public confidence”—which is hard to define and even harder to measure—the GMC is fast losing respect in the profession it seeks to regulate. They are seen as out of touch about the challenges of working on the frontline and worse still, their actions are viewed as jeopardising patient safety—one of the principal reasons they exist. This all comes at a time when the roles of the professional regulators are up for consultation.

Courtroom 3 saw the latest in the high profile case of Hadiza Bawa-Garba, a trainee paediatrician convicted of gross negligence manslaughter in 2015 after the death of six year old Jack Adcock from sepsis at Leicester Royal Infirmary.

The GMC is attempting to overturn a decision by the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service to keep her on the medical register.

In the words of one of the two presiding judges, it is a tragic case all round and one that has garnered huge public interest. Indeed, the press gallery was full and doctors were wearing badges saying “learn not blame”.

Alongside the doctors, Jack’s parents were in attendance understandably visibly angry and upset.

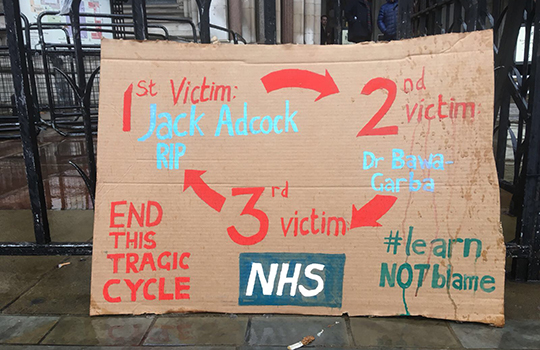

Outside a cardboard placard was painted with a “tragic circle.” The trainee paediatrician who had made the sign explained that it represented the idea that the first victim of medical error was Jack; the system failures surrounding Bawa-Garba’s mistakes made her a second victim; which, if not handled properly, would make the NHS a third victim. This would only further perpetuate the “tragic circle” creating yet more victims.

Outside a cardboard placard was painted with a “tragic circle.” The trainee paediatrician who had made the sign explained that it represented the idea that the first victim of medical error was Jack; the system failures surrounding Bawa-Garba’s mistakes made her a second victim; which, if not handled properly, would make the NHS a third victim. This would only further perpetuate the “tragic circle” creating yet more victims.

On social media Bawa Garba is not seen by many outside the profession as a victim. The Adcock’s anger has been shared by others, who see a privileged, patronising medical “club”—a word used in court—defending their own. There’s a pervasive view that doctors seem unperturbed by the death of a child and fail to understand that they’re not the only ones working in high risk environments.

Nigerian born, she has—perhaps predictably given previous experiences of overseas black and ethnic minority doctors working in the UK—endured an ongoing barrage of racially motivated abuse that’s now been reported to the police. She’s also been hit with allegations that she gave substandard care because she was prejudiced against Jack because he had a disability. Bawa-Garba’s own child has autism and she is a trained child behaviour therapist with expertise in working with children with special needs.

Bawa-Garba does seem to have the “club” on her side, however. But these aren’t just medical professionals who throw their weight behind any doctor. Indeed, they’re outspoken and proactive critics of perceived unethical behaviour by other doctors.

There’s just no consistency, one doctor commented outside the courtroom. Why do some serious mistakes resulting in tragic harm or death end up in the Crown or civil courts, a tribunal, a suspension, or erasure, and others don’t? And why are some doctors with criminal convictions pursued by the GMC as particularly damaging and others are not?

There’s a concern that the full situation hasn’t been properly understood. Statements made were met by disbelief by doctors in the galleries—the complexities of day to day working in a stretched NHS distilled in courtroom exchanges between the QCs and judges. Systems failures dismissed as passing the blame onto others—what was so different about this day, the judges asked. Many doctors work a “double shift,” one judge added.

Doctors who had worked with Bawa-Garba were aghast at this description. Seventy three system failures had been identified. She was working on 4 different floors covering multiple wards including respiratory HDU and admissions.

“She was doing the work of three doctors—the consultant, absent registrar who should have been covering the children’s assessment unit,” one said. She’d also appointed an SHO to chase up results because of the IT failure and so was doing their job too.

According to Jonathan Cusack, a neonatologist at the infirmary who became Bawa-Garba’s supervisor as part of her re-training following Jack’s death, a computer failure meant she was told Jack’s results over the phone rather than reading them on screen, making her more susceptible to “cognitive error.”

This is well described in the literature as increasing the risk for error and patient harm.

Perhaps the GMC’s own report—published a mere ten days before—warning that trainees were being forced to work beyond their capabilities and to run busy departments unsupervised putting patients at risk had got lost in the post, another doctor remarked.

Bawa-Garba has undoubtedly made mistakes. But she had been blamed for the fact that the consultant, when he arrived for evening handover, did not act on the blood gas results he was given by her. She has also been held responsible for not checking nurses were making the correct observations; for someone else giving blood pressure lowering drug enalapril—which she didn’t prescribe—when Jack already had sepsis. This was felt to be a significant contributory factor in his death by one expert—yet Bawa-Garba had no knowledge of the fact that it had been given.

The GMC’s Charlie Massey was quoted in the Daily Mail as saying: “At the heart of this tragic case was the sad death of a six-year-old boy, Jack Adcock, who did not receive the care he should have. We acknowledge the strength of feeling expressed by many doctors,” adding that “the decision to appeal the suspension was not taken lightly”.

But the concern amongst doctors is that this move will only perpetuate further the “tragic circle.”

Deborah Cohen is a freelance journalist.