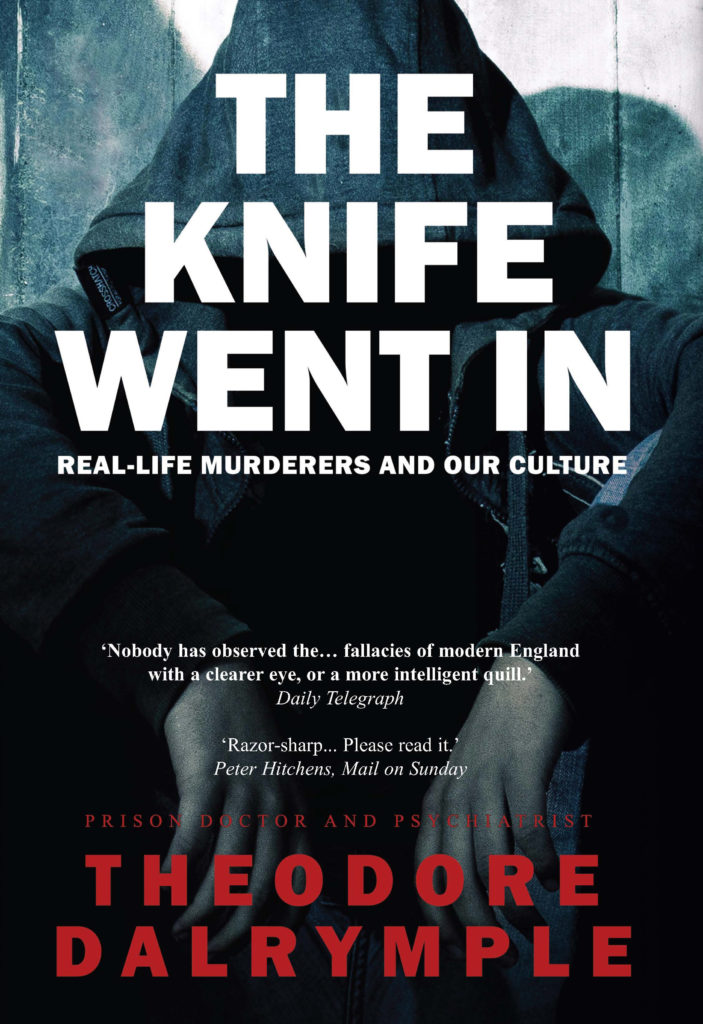

Theodore Dalrymple describes in his new book The Knife Went In the Britain he witnessed as a prison and NHS doctor, psychiatrist, and expert witness in criminal cases around Britain. In this edited extract, he details how the prison service introduced a new handle on suicides by prescribing “complex forms” to its staff.

Theodore Dalrymple describes in his new book The Knife Went In the Britain he witnessed as a prison and NHS doctor, psychiatrist, and expert witness in criminal cases around Britain. In this edited extract, he details how the prison service introduced a new handle on suicides by prescribing “complex forms” to its staff.

Prison administrators, like many in other bureaucratic organisations, seem to believe that for every problem that arises there is an equal and opposite form that, if filled out properly, will solve it. Once a form has been introduced, it achieves a kind of magical significance.

Thus when suicides in prison started to rise—to the consternation of the government—a form that was startling in its complexity was introduced into prisons to cover any prisoner who had showed the slightest inclination to suicide.

Helpfully, the Home Office produced a list of risk factors for suicide in prison—a list so comprehensive that it is doubtful whether there has ever been a prisoner who, according to it, was not at risk of suicide. Prisoners from broken homes, prisoners who take drugs or drink to excess, prisoners with histories of self-harm, unemployed prisoners, ill prisoners, first time prisoners, long term prisoners, prisoners with relationship problems, prisoners on remand, etc., etc . . . all might commit suicide.

Since thousands of prisoners show such an inclination or have such a background, form filling became one of the major tasks of prison officers.

From the administrator’s point of view this major absorption of manpower was merely a regrettable but necessary byproduct, as the real point of both the long list and the form lay elsewhere. If procedure had been followed as stipulated, the administration can claim, in the face of a suicide, that everything that could have been was in fact done. On the other hand, and this is much more likely where things are complex, if procedure was not followed to the letter then there is a ready made cause for the untoward event of the prisoner’s suicide.

After all, the mantra goes, if only the form had been completed correctly, the suicide wouldn’t have happened; or at least all that could have been done would have been done by the administrators! I have attended several inquests on suicides in prison in which the main question to be answered was whether the form was filled in correctly.

There is another attractive feature of such a complex suicide form—the culprit, or scapegoat, is evidently the person who has failed to fill in his bit correctly. Almost always the culprit is someone at the lower, or even the lowest, level of the hierarchy rather than at its top. Responsibility is shifted to someone in the organisation who has the least responsibility—the person to whom blame attaches itself can’t actually be blamed, and several birds are killed with one stone.

No enquiry into a death by suicide is complete without first an unctuous assertion that lessons have been learnt (only for something very similar to occur soon afterwards). The prison administrator knows that no one—least of all his political overlords—will ever query or investigate whether the proposed responses to a situation actually work, or make the slightest dent. Even less likely is that anyone will ever connect the overall amount of time spent on form filling to what is the major, if not single, means of suicide prevention.

After all, what guilty paper trail isn’t the gold standard of bureaucracies?

Complex form filling here is not just time wasting, though it often is. It also demoralises and degrades all staff, because it implies that, were it not for the forms, staff would not or could not do their work properly. So all consuming can complex form filling become that it no longer is a means to an end, but becomes the end itself. Once a form has been filled in, the work has been done and everyone can go home. One suicide at a prison I worked for as a doctor is a poetic example. It occurred while there was a skeleton staff on duty. The rest of the staff were away on suicide awareness training.

Theodore Dalrymple worked as a GP and a psychiatrist, first in the East End of London and later at a Birmingham hospital and the prison next door. He was for many years a columnist for The BMJ and previously the Spectator, and has written for the Times, Guardian, Daily Telegraph, and the Spectator and publications in Australia and the US. http://bit.ly/theknifewentin