To truly understand and improve outcomes, we will need to be brave

The publication last week of the National Maternity and Perinatal Audit (NMPA) shows that there is significant variation in practice and outcomes across maternity services in Britain. The provision of this baseline level of data should in theory allow us to monitor the improvements that are being made through the Maternity Transformation Programme and the Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative. Yet to truly understand and reduce variation we will need to be brave. We will need to take a critical look at ourselves and our practice and understand the human factors that make us slow to change.

The publication last week of the National Maternity and Perinatal Audit (NMPA) shows that there is significant variation in practice and outcomes across maternity services in Britain. The provision of this baseline level of data should in theory allow us to monitor the improvements that are being made through the Maternity Transformation Programme and the Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative. Yet to truly understand and reduce variation we will need to be brave. We will need to take a critical look at ourselves and our practice and understand the human factors that make us slow to change.

Healthcare is on a continuous journey of change. Change over time is partly due to new medical evidence—although translation from evidence to clinical practice is not straightforward. Studies show that there is an average time lag of 17 years. Change is in part limited by professionals’ understanding of new evidence, habit, and unconscious bias; patients also bring their own perspectives and expectations.

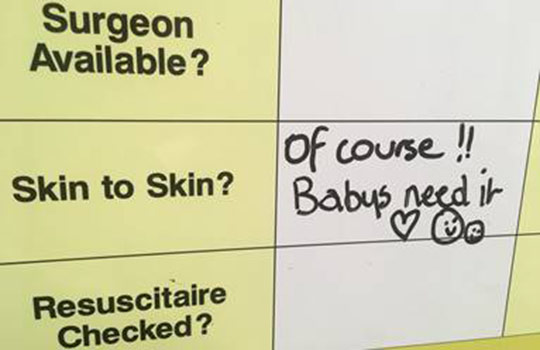

Individual courage and initiative are needed if we are to make change in complex systems, which tend to preserve the status quo. A key example mentioned in the report is the wide regional variation in the rate of skin to skin contact in the first hour of birth, despite there being longstanding evidence of the benefits of this for both mother and baby. Even as far back as 2004, NICE guidance recommended that healthcare professionals should facilitate early skin to skin contact between newborn babies and mothers at caesarean births.

An inspirational midwife I know, Jenny Clarke @JennytheM, became so frustrated at the lack of skin to skin contact in the operating theatre in which she worked that she climbed a ladder and wrote on the wall “Is the baby skin to skin?”

An inspirational midwife I know, Jenny Clarke @JennytheM, became so frustrated at the lack of skin to skin contact in the operating theatre in which she worked that she climbed a ladder and wrote on the wall “Is the baby skin to skin?”

Breaking the “rules” (what is accepted) and exposing yourself to the possibility of negative fallout is a personal risk. Yet the ultimate result here was a permanent whiteboard in the theatre asking the question “is the baby skin to skin?” and a change in behaviour, so that skin to skin became the norm at Jenny’s hospital, benefiting many mothers and babies.

The impact of Jenny’s actions reaches beyond her own trust. She continues to campaign for skin to skin contact by volunteering to speak at events, writing blogs, rapping, and spreading ideas via social media. Talking with Jenny about her work encouraged me to change my own practice. I also started to question and break “rules” little by little.

I started with skin to skin contact at caesarean section births, then new guidance was issued on the benefits of delayed umbilical cord clamping so I started that too. Then I started to question why I handed the baby to a midwife to take to the mother after caesarean sections, so I started passing the baby straight to the mother for skin to skin contact as soon as it was born—just as we would for a vaginal birth. As I pushed these small boundaries, subsequent improvements we could make began to unfold too. If the baby is skin to skin with its mother and we are delaying clamping the umbilical cord, then the next logical step was that the birth partner could cut the cord as this procedure was no longer in the sterile surgical field.

As I change practice, I also hope that I am acting as a role model for others to do the same. I know that we are currently a long way from achieving 100% skin to skin contact in the first hour. The NMPA recommends that “Clinicians should make every possible effort for all babies to have skin to skin contact with their mothers within one hour of birth, where the condition of mother and baby allows. For babies who are to be admitted to a neonatal unit, all efforts should be made to offer skin to skin contact prior to transfer of the baby where the baby’s clinical condition allows.” I really hope that this statement and the report make us reexamine our practice. Hopefully, we’ll then be brave enough, as Jenny was, to depart from our routine habits and take steps forward that will transform maternity care for the better.

Florence Wilcock is a consultant obstetrician at Kingston Hospital with an interest in intrapartum care and improving maternity experience. She is chair of the London Maternity Strategic Clinical Network user experience subgroup and co-founder of #MatExp, a grassroots movement aimed at improving maternity experience for families and the staff who care for them. She can be found on Twitter @FWmaternitykhft

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests:

• Employed by Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, associated with London Maternity Strategic Clinical Network, current project funded by NHS England Challenge Fund.

• Founder of MatExp—a change platform—with Gill Phillips of Nutshell Communications Ltd with whom I work closely.

• I receive no financial benefit from any of the above apart from my employer.