Artificiality is an ambiguous concept.

The Latin adjective artificialis (from ars, art, and facere, to make) was introduced by the Roman rhetorician Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (c. 35–100 AD), as a translation of the Greek word ἔντεχνος, artistic, artificial, or within the province of art; τέχνη meant an art, craft, or skill; a system, a method, or a set of rules for making anything; a work of art or a handicraft; and any means whereby anything was acquired, including an art, craft, or skill, but not exclusively so.

Image: A bust of Marcus Fabius Quintilianus

One of the twelve Caesars about whom Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus wrote in his famous book, De vita Caesarum (AD 121) was Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, whose final days he described: “Tunc uno quoque hinc inde instante ut quam primum se impendentibus contumeliis eriperet, scrobem coram fieri imperavit dimensus ad corporis sui modulum, componique simul, si qua invenirentur, frustra marmoris et aquam simul ac ligna conferri curando mox cadaveri, flens ad singula atque identidem dictitans: ‘Qualis artifex pereo’.”

Robert Graves’s translation, to which I have made minor changes, captures the text well: “Finally, when his companions unanimously insisted on his trying to escape from the miserable fate threatening him, he ordered them to dig a grave at once, of the right size, to collect any pieces of marble that they could find, and to fetch water and wood for the disposal of his corpse. As they bustled about obediently he muttered through his tears: ‘Dead! And so great an artist!’”.

Nero had prepared poison to take, but his valets absconded with it. He had called on gladiators to execute him, but none would oblige. He had considered drowning himself in the Tiber, but could not bring himself to do it. Finally, he summoned up the courage to stab himself in the throat, with the help of his scribe Epaphroditus. He died before he could be captured by the soldiers who had been sent by the Senate, at whose hands he expected an even worse death, by flogging, in revenge for the atrocities he had perpetrated.

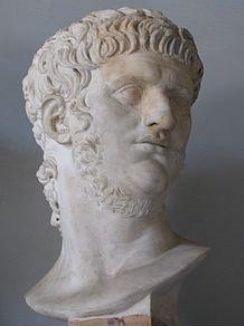

A bust of the emperor Nero (37–68 AD); Suetonius described him thus:

Height: average

Body: pustular and malodorous

Hair: light blond

Features: pretty, rather than handsome

Eyes: dullish blue

Neck: squat

Belly: protuberant

Legs: spindly

It is not clear what kind of a great artist (artifex) Nero considered himself to be. Artifex could mean an expert practitioner of an art, and Nero considered himself to be a great musician. However, it could also mean a master schemer, one adept at cunning plans; even at the end he was deluding himself into thinking that if he apologised properly to the Roman people in the forum, he could persuade them to pardon his sins and make him prefect of Egypt.

This illustrates the ambiguity that arises from the use of “artificial” to mean either skilfully made or, alternatively, cunning and intending to deceive. But the primary meaning of the word is “opposed to natural”, which is where its history in the English language begins.

“Artificial” appeared in English at the end of the 14th century, describing the duration of daylight. Here is Chaucer in the introduction to the Man of Law’s Tale: “Our Hoste saw well that the brighte sun / Th’arc of his artificial day had run / The fourthe part, and half an houre more . . . ” And in his book A Treatise Upon the Astrolabe (1391, Part II, Section 7), said by R T Gunther in Early Science in Oxford (Volume 5, Chaucer and Messahalla on the Astrolabe) to be “the oldest work in English written upon an elaborate scientific instrument”, Chaucer explains that the artificial day is “The arch of the day . . . from the sonne arysing til hit go to reste.”

However, before long, “artificial” came to mean made by human skill. It has been medically linked to many terms, including blood vessels, cells, chromosomes, diets, insemination, joints, lenses, membranes, metalloproteins and metalloenzymes, microtubules, molecules, neural networks, nutrition, organs, pacemakers, pancreas, photosynthesis, radionuclides, RNA motifs, saliva, selection, sperm, sphincters, sweeteners, target DNA sequences, tears, vesicles, and of course intelligence. Dermatitis artefacta is a condition in which skin lesions are self-inflicted, usually implying some psychological problem, or occasionally in order to make an insurance claim. It is seen more often in women than in men; they are usually in their teens or 20s and consistently deny that the rash is self-induced. The lesions, which can take any form (erythema, swelling, blisters, denuded areas, crusts, cuts, burns, and scars), are generally of a bizarre shape, with irregular outlines, well demarcated from the surrounding normal skin.

When I searched PubMed for “artificial”, even restricting occurrences to the titles of papers, I got nearly 40 000 hits. It appears that there is little that cannot be made or achieved artificially.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.